Marikana: Economic impact one year on

- Published

Wage disputes were at the centre of the protests a year ago; unions are still fighting for higher wages

It's a crisp August morning in Johannesburg and the churn of the local news media slowly reminds people about the moment, one year ago, when things took a turn for the worse in the mining community of Marikana.

At this time last year 34 mineworkers were killed in a violent confrontation with the South African police, after an industrial dispute turned ugly. The dramatic pictures were beamed across the world, showing resolute men carrying machetes confronted by plumes of gunfire and smoke.

This was a watershed moment in the new South Africa, a country that has elevated the "bill of rights" as the pillar of its value system.

In the days after the tragedy at Lonmin's Marikana mine it remained unclear who was to blame for the violent and deadly outcome, and unfortunately one year later there is still no clarity.

The tragedy has left Africa's wealthiest economy anxious for peace and equilibrium to be restored.

Wake-up call

The importance of mining to the South African economy has been shrinking for years, and it now contributes less than 10% of GDP. In addition, the process of extracting resources has become more expensive and dangerous as mine shafts go deeper below the earth's surface.

Despite these challenges, Peter Leon, a respected mining analyst, says the sector cannot be written off from the larger economy. It remains the largest generator of foreign exchange earnings and it is the largest private employer in the country.

For Mr Leon what is worrying is that since Marikana, "South Africa has seen a downgrade of its international credit ratings, the local currency weakened and business confidence decline."

The South African rand has fallen 15% against the dollar in recent months, and while it is still too early to tell whether investment has fallen, analysts agree that something needs to be done and quickly.

But Mr Leon adds that if anything good came out of Marikana it is that it acted as a wake-up call for the government "which will force it to stop dawdling on industry reforms".

Framework

There is much debate over what these reforms should be. For the workers, change would entail higher wages and better living conditions on the mines.

What remains important to the mining companies is greater policy certainty, a productive labour force and higher commodity prices globally.

The government is working on a framework agreement between all stakeholders, aimed at bringing much-needed stability to the industry, but some unions are unhappy with it.

Until there is clear guidance from the government on how these issues can be resolved, more strikes are almost inevitable, which does not bode well for South Africa's image as an attractive investment destination.

Union politics

Another thing to have come out of the Marikana tragedy is the emergence of the Association for Mineworkers and Construction (AMCU) as a much stronger force.

The wage dispute at Marikana was exacerbated by tensions between AMCU and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). At the Lonmin mine, AMCU has now displaced the NUM as the biggest union at the mine.

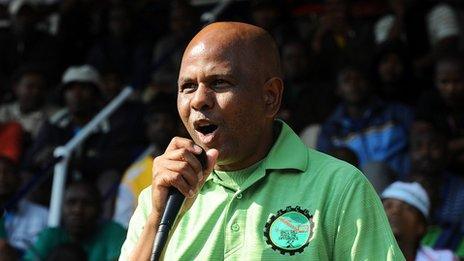

Joseph Mathunjwa wants the government to do more

The president of AMCU, Joseph Mathunjwa has become the face most associated with Marikana.

On the surface he is a calm and affable man, dressed in casual khakis. Yet his appearance belies a steely resolve to introduce a "second revolution in the mining sector".

"[The protests will] go on, unless the government offers some help with the situation," he tells the BBC.

The meteoric rise of AMCU is a trend that many analysts are watching closely. After all, the NUM has a 31-year history in South Africa, having been formed against the backdrop of apartheid.

Frans Baleni, the NUM secretary-general, notes that during the apartheid era there was a common enemy in the form of the regime security police. Today he is baffled that "it's worker killing another worker". In his view, this is the dynamic introduced by events at Marikana.

When quizzed about the shifting balance of power away from NUM to AMCU, he simply responds: "We have not been discredited… soon people will know that they've been lied to."

Redress

While the unions posture and compete for members, and the government considers how to modernise a system of mining that was inherited from the apartheid state, there are also calls for the South African police to be trained to handle labour unrest with greater sensitivity.

For now though, the most pressing issue is redress for the families who lost someone in the Marikana mine tragedy.

The state-sponsored Farlam Commission of Inquiry is meant to facilitate that process, but it's bogged down by financial problems.

For many, the perceived success of this commission will be the litmus test of whether South Africa has truly reflected on the events of 16 August 2012.

- Published15 August 2013

- Published11 July 2013