The importance of being paranoid

- Published

Of all the people I've ever interviewed one sticks out.

Most people who reach the top of an organisation have been asked every question there is to be asked on their way up.

Understandably their answers in interviews betray that experience - they'll give you a honed, tried-and-tested response, rather than the one that really answers what you were asking.

But not Andy Grove. He is the former chief executive of the computer chip manufacturer Intel. This giant corporation was the beating heart of hugely increasing computer power for several decades from the 1970s onwards.

Another former Intel chief executive Gordon Moore, was the visionary who drew up what became Moore's law on (I think) a table napkin: that's the observation that the computing power on a single silicon chip is doubling every two years or so. It continues to do so.

Moore's law is not really a law, of course, more an observation about the pace of computer development that has been going on for a lot longer than the PC era.

What the "law" does do is provide the world's huge semiconductor industry with a research and development roadmap.

It enunciates the pace of innovation that seems to determine the pace at which new chip-making machines have to be developed.

It is an extraordinary progress, and one which has to a large extent determined the evolution of the whole microchip business itself for the past several decades.

Destructive happening

Anyway, as I was saying, if you asked Andy Grove a question he would think before he replied... and then (judging by the precision of his answer) he would give you the impression that if you had asked a really telling question, he would take it so seriously that the future direction of the company might be changed as a result.

As it happens, I never did ask that question, but this was the feeling that Andy Grove gave you. He listened, took in the question, and then responded to it. And he ran a very tight ship indeed.

He is also notable for enunciating an observation that is worth a bit of consideration. It is summed up in the title of one of his books: Only the Paranoid Survive.

In essence, this is easy to grasp.

Intel has been affected by the growth of smart phones wanting low energy chips

It happens when a company has clawed its way to the top, competed the hell out of its rivals, when everything is going swimmingly, not a cloud on the business horizon. That is when disaster strikes.

It's the local store with a town tied up in its grasp, bathing in monopolist prosperity. Then Walmart opens up 10 miles down the highway. It's the giant railroad monopolies that fail to spot the coming of the regional airlines. It's Motorola mobile phones before Nokia, or Nokia before Blackberry, or Blackberry before the iPhone.

People running companies need to be attuned to this kind of potentially destructive happening, says Andy Grove. They need to be paranoid about the ever present possibility of it happening.

Changing world

In a way, Andy Grove's deep-seated concern about corporate paranoia does not go far enough. You might say that it is not enough that success should be accompanied by boardroom paranoia.

A more detached, less strategic view might be that success actually sows the seeds of its own business destruction. That failure is almost implicit in success.

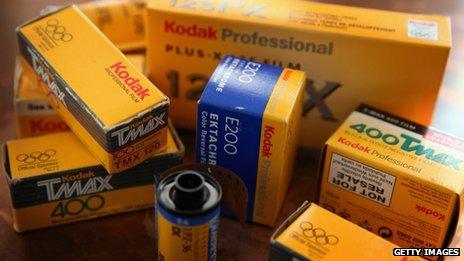

Kodak was the global giant of analogue camera film

It happens like this. Inspired by an invention or technology breakthrough, a company flowers and flourishes, pushing erstwhile rivals aside. It expands ferociously, redefines the market, brings huge rewards to its shareholders and plaudits to its top people.

And the bosses begin to believe in their headlines. They become as awestruck as their admirers. They believe they have devised a business methodology that will last decades or even centuries.

Around a company, success builds a carapace as thick and impregnable as a tortoise shell. The bosses believe they know what their customers want. Their vast investments in plant and equipment insulate them from the disruptive impact of a changing marketplace.

And then one day they realise that their world has changed... and there is little they can do about it.

Kodak warning

You can see this process rather uncannily at work in the city of Rochester in New York state. Two world famous companies based there, who had two global markets tied up, are now pale shadows of their former selves.

Kodak owned photography for almost 100 years. The company actually invented the digital still camera, but its success with film had been overreaching that it could not take digital seriously until it was pretty much too late to respond.

When it went into digital cameras, they were rapidly becoming a commodity, something which over the decades, Kodak film never did.

Xerox invented photocopying, or Xeroxing as we used to call it. It also invented other things we now take for granted, such as the personal computer and the ethernet.

But the computer devices were invented 3,000 miles across the continent from Rochester at the celebrated Palo Alto Research Centre in Silicon Valley, California.

Xerox was making so much money out of copying that it did not have to take computers seriously - even when the breakthrough technology innovations were coming out of its in-house research lab, albeit a long way from corporate HQ.

Which takes us back to Intel. For decades, steered by Moore's law and driven by the rising predominance of the desktop and the laptop computer, Intel thrived. It had few rivals, and they were not very profitable.

But the computer landscape changed. Suddenly - with the rapid rise of mobile computing - there were other considerations than the amount of processing power that could be squeezed on to a chip.

Mobile computing puts low power at high priority. The implicit operating system alliance between Intel chips and power hungry Microsoft software came under strain from tiny outsiders.

Now we have started on a great fragmentation of computing, mobile machines that need very different chips than the ones Intel made its reputation with, running software that is not necessarily Microsoft's.

Intel is trying to tackle the disruptive move to mobile. It is refocusing its business to use its acclaimed manufacturing prowess to make chips on behalf of other companies, not something the industry leaders would have been happy with in the past.

Yet with Intel still suffering from falling profits as it aims to get to grips with the growth of mobile computing, it is possible that Andy Grove's successors may have forgotten his warning about the need to be paranoid.