Australia seeks growth in new sectors

- Published

Australia's economy, which enjoyed robust growth in recent years, has seen its growth rate slow of late. With the mining boom tapering off, Ali Moore asks where future growth will come from.

Geelong used to be a city that made things. An hour's drive south-west of Melbourne, the tall thin smoke stacks of the Shell oil refinery are the first sign of industry as you approach the outskirts of the city.

Next come the sprawling factory buildings emblazoned with the Ford logo, which for nearly 90 years have served as proof Australia is a manufacturing nation.

But now, the refinery is up for sale, and come 2016, Ford will close its gates for the last time.

Geelong is being forced to reinvent itself. And the challenge facing the city is the same challenge facing the country.

"I think Geelong tends to be a bit of a microcosm of Australia," says the head of the Geelong Chamber of Commerce, Bernadette Uzelac.

"Our traditional manufacturing industries have been in decline for some time and struggling due to the global conditions and the high Aussie dollar."

Ford's Geelong factory is hard to miss but the car giant will shut all its Australian manufacturing plants by October 2016

One door closes

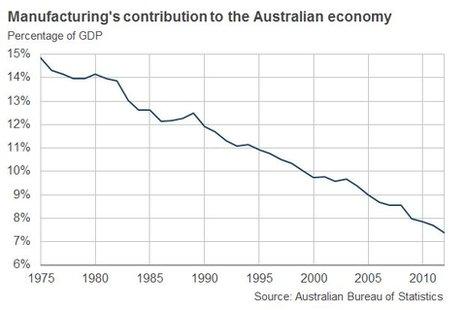

Across the country, manufacturing's contribution to the economy has been shrinking for decades.

At its peak in the early 1960s, the sector was responsible for almost 30% of Australia's economic output. Now, it's just 7%.

Once it employed one in every four workers, now it's one in 12.

That didn't seem to matter so much when the country's mining boom was in full swing. But with that boom slowing, where will the jobs and the growth of the future come from?

Jobs for people like Henry Fuller. For 27 years Henry has been on the assembly line at the Ford factory in Geelong.

When he started, he thought it was a job for life. Now at 51, he's about to re-enter an increasingly crowded employment market. "One door's closing and I hope another one opens," says Henry. "That's just the way you've got to look at it."

Henry Fuller will have to turn his production line skills to a new industry

Henry will be offered retraining by Ford, and is as optimistic as he can be about finding another job.

But the skills of the future are likely to be very different from the skills of the past.

Transition

Mark Thirlwell charts global economic trends for the Lowy Institute for International Policy in Sydney.

He says Australia will continue to export resources, but future economic growth will come from services, especially those aimed at the expanding Asian middle class.

"Some of that will be the food and agriculture sector," he says. "Some of it's going to be in services, tourism we're seeing signs of it already.

"We'll see some come back in manufacturing but it's going to be high-end niche stuff, otherwise it's still a very tough world out there for developed-economy manufacturers.

"And some of it's going to come from new service sectors that we haven't really explored yet, but as that Asian demand comes on we'll start tapping into it."

Changing collars

In Geelong it's a transition already under way.

Bernadette Uzelac says the city is rapidly moving towards the services sector, with new jobs in health, education and science.

Geelong has been a big beneficiary of government help, with various government agencies relocating their operations to the city, speeding up the process of turning blue collar into white collar.

Richard Kerr, from Farm Food, sells meat products to Asia

And Geelong has smaller niche manufacturing operations, such as the ones Mark Thirlwell refers to.

The family-owned business Farm Foods churns out half a million beef patties and a million sausages every week.

Some of that is sold to Asia already, and within 10 years the company hopes to export half of what it makes to the region.

Director Richard Kerr says future growth lies in food for export, but the focus had to be on the right industries.

"We need to specialise in what we know, and what we have and what other people don't have, and not just go head to head with other countries."

Different skills

There is no shortages of ideas for the source of future growth and jobs for Australia. The challenge is turning the ideas into reality in time.

The mining boom has waned, manufacturing is employing fewer and fewer people, and new industries don't happen overnight.

The Lowy Institute's Mark Thirlwell says life is going to become more complicated.

"One economic model [of] digging stuff out of the ground, putting it on boats and shipping it across to your consumers - that requires some work and some effort, but it's a different sort of skill set to integrating with your consumer to selling them services for example, to getting on the ground and understanding the culture.

"There's no automatic fact that says things have to turn bad. The risk for us is we'll have to work harder, and having had more than two decades of not necessarily having to work that hard and discovering suddenly that we have to start working harder, that's the challenge I think. "

It's a challenge that is daunting for workers such as Henry Fuller.

He's worked hard all his life, but he'll need all his optimism and determination to turn his production-line skills to an entirely new industry. He has plenty of company though, as he starts the journey.