Gem-encrusted mooncakes, corruption, and the law

- Published

- comments

Linda Yueh explains why traditional mooncake gifts have become controversial

In business, you sometimes hear that it's not what you know, but who you know.

At the risk of depressing parents about the tens of thousands spent on their children's education, connections are important in business.

Well, going to a good school probably raises the chances of meeting other well-connected people.

But, where is the line between making connections and crossing over into corruption?

It is a particular challenge for business in China due to the cultural importance of having good inter-personal relationships.

I wrote about the concept of Chinese guanxi a little while ago when I expected that the GSK troubles with the Chinese authorities would not be an isolated case.

Under the new Chinese leaders' anti-corruption drive, numerous big companies and Chinese officials have fallen afoul of that line.

Earlier this summer, the Chinese authorities launched investigations against British firm GSK and other Western pharmaceutical companies (Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Novartis) for alleged bribery of doctors to prescribe their drugs.

Then, JP Morgan's hiring practices in China came under investigation by the US government. It was over their employment of the children of powerful Chinese officials, known as "princelings", and whether they were linked to specific deals in China as reportedly seen in an internal spreadsheet of their "Sons and Daughters" department.

Some 200 hires are being scrutinised by the SEC, including the daughter of Zhang Shugang, a powerful railway ministry official, who is himself under investigation by the Chinese government for corruption.

Recently, we have seen the most high-profile dismissal so far under the new Chinese leaders: Jiang Jiemin, the head of the body that oversees all of China's large state-owned enterprises, known as SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission). And of course, Bo Xilai, who is awaiting his verdict.

Looking back, for companies working in China during the 1990s when it was just opening up its consumer market, having good connections with the Chinese government facilitated doing business in an environment where state-owned enterprises dominated.

With greater opening of the market, perhaps it's become less important. But, relationships remain an essential part of doing business in China as elsewhere.

Nepotism and the hiring of relatives are not unheard of in Western firms. The issue, though, for JP Morgan and others under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act is whether there was a quid pro quo for a specific deal in return.

Enforcing the rule of law

For China, enforcing its laws is seemingly a priority for the new president and premier. Premier Li Keqiang in his speech today at the World Economic Forum in Dalian, China, aimed to reassure the assembled foreign businesses that there is a level playing field for them vis-a-vis state-owned enterprises.

The perceived lack of one has been a source of complaint for much of the past decade since China agreed to give multinational companies more market access when it joined the World Trade Organisation in December 2001.

So, improving the effectiveness of laws and driving out corruption are seemingly high on the government's agenda.

But, questions remain over whether the anti-corruption drive to enforce the law is a serious effort or tokenism.

One of the reasons for the recent fervour is that once a country gets richer and develops a large middle class, that middle class would like to have its rights safeguarded.

In a one-party state where there are no democratic safety valves, it is hard to have that assurance.

So, what China has done is to reinforce the rule of law, almost as a substitute for lagging political reform.

Chinese citizens rely on the legal system to protect their property. And combating corruption whether it's foreign companies or government officials reinforces the rule of law.

A key problem though is that China doesn't have an independent judiciary. The courts are an administrative arm of that one-party state run by the Communist Party.

The real test for the rule of law isn't the Bo Xilai trial, despite the publicity. Perhaps it will be when an ordinary citizen wants to enforce the rule of law against a high-ranking official.

If the rule of law comes up against the interest of the rule of Party, then that would be an indication as to whether China's anti-corruption drive and indeed the effectiveness of the legal system, which is fundamental to a stable market economy, can succeed.

Mooncakes

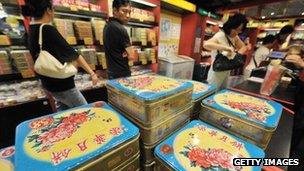

Shoppers inspect boxes of "mooncakes"

Coming back to that line between corruption and guanxi.

The latest ban is using government money to buy gem-encrusted mooncakes, a Chinese speciality cake that is similar to the British fruitcake in that it is eaten during special occasions.

The value and the sales of mooncakes have apparently fallen noticeably, probably because those costing 1,000 RMB (over £100) have disappeared from the shelves.

This really didn't sound like such a good idea in the first place. Gem-encrusted mooncakes, corruption, and the law.