Is the Fed frightened of its shadow?

- Published

- comments

A week ago, a very successful and smart investor said to me that the debate over the Fed's taper - whether the world's most powerful central bank would start reducing its $85bn-per-month money creation programme - had turned into a big yawn.

It was perfectly obvious, he said, that Ben Bernanke and his crew would sit on their hands and do nothing.

How so, I asked? Surely unemployment was falling towards the 7% rate that is supposed to be the threshold for the end of those massive conversions of debt into money, and therefore the time had arrived for a first small reduction in the rate of money manufacturing.

"Ah, you are looking in the wrong place" he said. "Look at what's happening in the US housing market."

And here is where it all gets slightly surreal, and you may feel you are losing your mind.

As you will know, partly because I've been banging on about it for months, the mere expectation that the Fed would start to buy fewer bonds (it creates money by purchasing government bonds and mortgage-backed bonds issued by the official housing market agencies) had led to a fall in the price of those bonds.

When the price of those bonds falls, the yields on them rises. And the yield on those bonds are the most influential important interest rates in the US economy, which determine most other interest rates both in the US and the rest of the world.

Or to put it another way, just the expectation - rather than the reality - that the Fed would create less money led to an increase of a full percentage point in arguably the world's most important interest rate, the US Treasury's 10-year bond.

Now if you think of the world's markets as a vast pond, this rise in US government-bond rates is a bit like chucking a stone the size of Ben Nevis into the middle of it. The ripples haven't quite been the size of tsunami, but they've been hair-raising for all the little boats floating on the pond.

So, for example, international investors, seeing that it is now possible to earn a more attractive return from investing in the world's biggest and (arguably) strongest economy, have taken a ton of money out of the supposedly riskier economies, most notably India - such that the currencies of the emerging economies have taken a hammering and the cost of money for them has in effect been raised significantly.

By the way, and to digress for a second, the sheer scale of US money creation, or quantitative easing, in the US has probably set back the cause of better co-ordinating the world's biggest economies by a generation - because all the world's rising economies in Asia and South America see is a US setting the price of money in a way that suits its domestic needs, and never mind the inconvenience and periodic shocks it causes them.

The point is that there is very little evidence that the Fed cares a fig about whether its rate of creating money is good or bad for the rest of the world.

It hasn't decided to keep up the pace of money creation to suit India.

So why has it decided not to taper at this juncture? Why hasn't it slowed the rate of money creation?

If you've been concentrating and have stuck with me, you've probably worked it out,

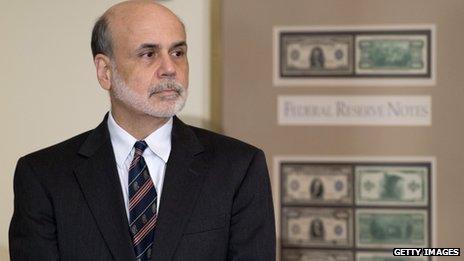

Ben Bernanke, Federal Reserve Chairman

The expectation of less money being created led to a rise in US mortgage rates, which has already started to dampen the US housing market, which in turn is expected to dampen America's recovery.

To put it another way, the Fed simply hinting that less money would be created, means that there will be no reduction in the amount of money created (for now at least).

Trebles all round - the unprecedented monetary stimulus goes on, sine die, and debt and equity markets all over the world surge.

The economics of the mad house, you might mutter, I suppose. Is it healthy that the Fed appears to be frightened of its own shadow?

Well, only one member of the Federal Reserve Board - the collective Fed eminences that makes these monetary decisions - seems to fear that the longer the central bank goes on reinforcing the addiction of economy and markets to money creation, the harder it will be to go cold turkey

Esther George is recorded as being "concerned that the continued high level of monetary accommodation increased the risks of future economic and financial imbalances, and, over time, would cause an increase in long-term inflation expectations".