Harvard plans to boldly go with 'Spocs'

- Published

Online courses have attracted millions. Now they are experimenting with limiting numbers

Keep up, keep up. If you've only just caught on to the concept of online university courses called Moocs, then you're in danger of falling behind again.

Harvard, one of the world's most influential universities, is moving on to Spocs - which stands for small private online courses. Nothing to do with Star Trek and sombre Vulcans, but plenty to do with ambitions "to boldly go".

And could these be the real deal? The academic chairing Harvard's online experiments says we are already "post-Mooc".

Moocs - massive open online courses - have been something of a hurricane in universities, making a lot of noise and promising to rip everything up.

Pioneered by some of the most prestigious US universities, they have been re-packaging course units into online lessons and making them available to anyone with an internet connection.

But it's still not clear whether this is a passing storm or something that will fundamentally change how higher education is delivered.

Last week the UK joined the fray, with more than 20 universities launching an online platform called FutureLearn, which will challenge the dominant players on the east and west US coasts.

Small is beautiful

The biggest success for online courses and their greatest problem are the same - the huge numbers attracted.

Students on campus are also using the online materials available for free

It demonstrates the scale of the unmet demand for higher education, but at the same time it's not clear how tens of thousands of students on a course could ever satisfactorily be taught, assessed and accredited. Most of these signs-up will sign off without completing courses.

At Harvard, more people have signed up for Moocs in a single year than have attended the university in its entire 377-year history. That's a great success story in opening up education, but what do you do with all those hungry minds?

Enter the Spoc. And the clue is in the "small, private" part of the name. These courses are still free and delivered through the internet, but access is restricted to much smaller numbers, tens or hundreds, rather than tens of thousands.

It means a selection process for applicants and the capacity for a more customised experience. Looking further down the track, it wouldn't be difficult to imagine fees and course credits.

Harvard and University of California, Berkeley, part of the edX online alliance with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, are among the universities beginning to experiment with this more refined model.

National security

Next week a popular and highly topical course in US national security strategy will begin at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. Alongside the campus students in Cambridge, Massachusetts, there will be a parallel Spoc version with a limit of about 500 online students.

The national security course will be available to 500 students studying online

Students wanting to get into this online classroom have to submit a written assignment about the US government's response to the conflict in Syria, along with details of their academic credentials.

Even though this online course won't have a formal academic credit at the end, it's going to require eight hours of work a week and a capacity to tackle questions about "Iran's nuclear ambitions, the slaughter in Syria's civil war, WikiLeaks and the publication of classified information".

These Spoc students might include Harvard students who couldn't get into the campus course, alongside those who might be studying from home or at work.

Harvard isn't abandoning Moocs, but rather like Russian dolls sitting inside each other, a single course might now be delivered to a large open Mooc audience, to a much smaller number of Spoc students and then down to an even smaller number enrolled at the bricks-and-mortar campus.

It's taking the limited and expensive resource of a Harvard course and amplifying it for widening rings of audiences.

Prof Robert Lue chairs the committee of academics that runs Harvard's online experiments, under the banner of HarvardX.

He describes the current online learning experiments as a "remarkable moment of possibility".

And he sees the move towards more flexible and refined formats such as Spocs as an "almost inevitable evolution".

Exam proof

"The Mooc represents just the first version of what we can do with online education," says Prof Lue. And this first version has now been overtaken. "We're already in a post-Mooc era."

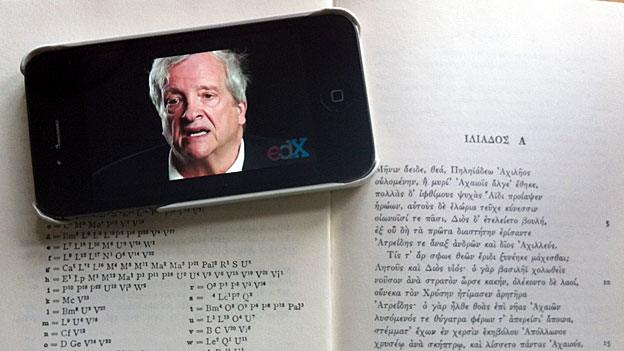

Recording material for Harvard's online learning project

"What has become very clear is that the engagement you get from a very large group with a wide-ranging set of priorities can be radically different from what you get from a more focused group," says Prof Lue.

It also paves the way to tackling one of the biggest problems for Moocs. How can they provide formally-recognised qualifications?

The smaller class size will allow "much more rigorous assessment and greater validation of identity and that will be more closely tied to what kind of certification might be possible," he says.

"It's safe to say that in the quite near term there will be announcements of experiments in this area."

There are voices of caution about over-hyped expectations for online learning.

A report published last week by the UK's Department for Business, Innovation and Skills suggested there remained many uncertainties over Moocs.

The lack of a clear business model was described as a "burning issue".

The edX project is in the fortunate position of being given $60m by Harvard and MIT, but few universities have the resources to give away so much expensively-produced content and staff time.

Digital challenge

Prof Lue suggests that the really tough questions raised by Moocs are not only about online learning but about what it means for the rest of the traditional campus.

Online learning's biggest impact could be on how conventional courses are taught

"What is it that a student gets out of being on campus and being in the classroom?"

If students on campus prefer learning online, what does it mean for the funding model for universities? What happens if a recorded online lecture is preferable to a mediocre live talk? How do universities show their "added value"?

Prof Lue argues that the significance of Spocs is that online learning is now moving beyond trying to replicate classroom courses and is trying to produce something that is more flexible and more effective.

Universities that ignore such developments, or think that Moocs can just be showreels for conventional courses, are putting themselves at risk, he suggests.

"The really big questions for university are about what students get from the classroom, what works, what could be done better."

"Institutions that sit back and watch, they may be in trouble. One can imagine a large institution where there isn't much difference between online and classroom - and then you'd be silly not to realise there's a problem."