Make-It-Yourself: The rise of the micro-manufacturers

- Published

Designers and inventors can now turn their dreams into reality at a fraction of the cost

The next industrial revolution is under way - make-it-yourself.

Thanks to state-of-the-art design software and the latest computer-controlled laser cutters, 3D printers and other manufacturing hardware, designers and inventors are turning their ideas into reality and getting them to market far more quickly and cheaply than they ever could before.

Digital designs sent online to micro-factories situated locally or abroad are reducing costs, waste and supply chains.

And the objects being made are not just your traditional arts-and-crafts fare in plastic and wood, but high-tech gadgets and inventions that have gone on to sell millions - and make millions - around the world.

For example, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey is the man behind another highly successful company, Square, which makes mini payment card readers that can plug into your smartphone or tablet.

The company has taken on the US merchant banking industry and is already worth $3.2bn (£2bn) after just two and a half years.

Square prototypes were created in a public access workshop in Menlo Park, California

Virtual made real

Square co-founder, Jim McKelvey, made the prototypes for the dongle in a community-owned workshop in Menlo Park, California.

It is one of several sites founded by TechShop, a pioneer in the "make-it-yourself" movement.

Members pay $125 a month for access to more than $1m worth of hardware and software, including mills, computer numerically controlled (CNC) routers, laser cutters and 3D printers, as well as classes on how to use all the technology.

"You get access to your own personal research lab for the cost of a bad coffee addiction," says TechShop chief executive Mark Hatch.

Founded in 2006 using money raised from amateur investors and passionate makers, TechShop has six centres in the US, each with around 1,000 members.

But the company has just announced its intention to raise $60m from corporate and private investors to fund its expansion.

Using 3D design software from the likes of Autodesk, says Mr Hatch: "You can do all your modelling in the virtual world and then make them real."

Some of the prototyping for the world's fastest electric motorbike took place at TechShop

Software then converts the design into instructions for the specific machine the designer wants to use.

Mr Hatch rattles off a number of other TechShop success stories, including Type A Machines, a 3D printer manufacturer; Clustered Systems, which makes lower-energy cooling systems for data centres; and Lightning Motorcycles, creator of the world's fastest electric motorbike.

"These stunning innovations coming out of the maker movement are beating some of the biggest companies in the world," says Mr Hatch.

"It's the democratisation of the industrial revolution."

Entrepreneurship

Prof Neil Gershenfeld, director of the Center for Bits and Atoms at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston is developing a similar concept with his Fab Labs - local digital fabrication centres aimed at stimulating invention and entrepreneurship.

Maiko Kuzunishi's laser-cut bamboo clocks are now sold around the world

There are about 150 Fab Labs dotted around the world in what the Fab Foundation describes as "a distributed laboratory for research and invention".

According to a study by 3D printing industry analyst Wohlers Associates, the sale of "additive manufacturing" products and services will reach $3.7bn by 2015, rising to $10.8bn by 2021.

"In 20 years this new industrial revolution is going to have a much larger impact that the internet ever had," says Mr Hatch.

"This is about the physical space, not the virtual space. It is already re-creating world."

'Tipping point'

Derek Elley, co-founder of Ponoko.com, a make-it-yourself service provider, agrees.

"In the past you had to go and convince a manufacturer to make your prototype, then convince a retailer to stock your product.

"Now digital manufacturing and the internet have made it so much easier for you to create, make and sell your products," he says.

"We're at a tipping point in terms of the technology."

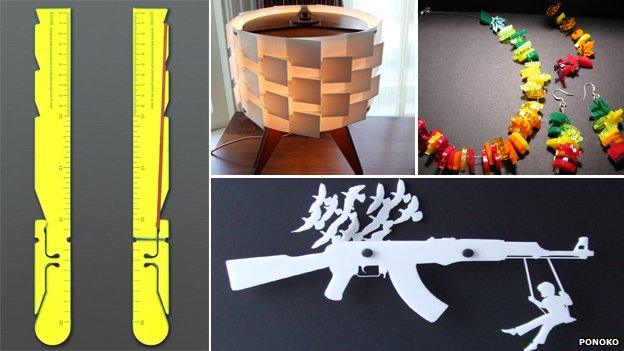

Ponoko has 100,000 designers using its services who have produced more than 300,000 products in total, says Mr Elley. There are five manufacturing hubs around the world - Italy, Germany, San Francisco, New Zealand and London.

Although wood is still popular, makers now have a wide range of materials available to them

Maiko Kuzunishi, a US-based graphic designer, says Ponoko enabled her to transform her bamboo-clock-making business from a bedroom-based hobby into a global business, shipping products all around the world and turning over hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

Creating the designs using Adobe Illustrator, she sends them to Ponoko for laser cutting and sells them on her own site and in online marketplaces, such as Etsy.com.

She has distributors in South Korea, Japan and Australia and retailers in Hong Kong, Germany and Belgium also stock her products.

"New technology allows an individual like me to become independent and create a micro-business," she says.

But she admits small-scale manufacturing is still more expensive per item than traditional mass manufacturing.

"Every dollar the customer pays on the product is not wasted because most products are made on-demand, so inventories and overheads are small and there is minimal waste of natural resources."

More materials

As the technology has developed the range of materials designers and inventors have available to them has proliferated.

It now includes gold-plated steel and coated ceramic as well as the traditional plywood and plastics.

"Digital technology is lowering design and manufacturing costs by factors of 10 and 20 times," says Mr Elley. "The cost of 3D prints has fallen by at least 300% over the last 10 years."

In the new era of efficient, flexible, distributed manufacturing he looks forward to the day when designers are treated like rock stars.

As the make-it-yourself revolution gathers pace, that day may not be far away.