Could power plants of the future produce zero emissions?

- Published

Net Power says that, if built, its power plants would not release any gases into the air

Could the smoke stack of a power station soon be a thing of the past?

Today, fossil fuel power stations are usually built with towers that emit vapour as well as greenhouse gases into the air.

But what if a new kind of power station could create electricity without belching harmful gases into the air?

Despite the development of renewable technologies, fossil fuels are still used to generate the overwhelming majority of the world's power, external, and it is likely they will continue to do so for many years.

In the US, external, about 70% of the country's electricity comes from burning fossil fuels. Other major economies, such as China, are even more dependent.

But now Net Power, based in the US state of North Carolina, believes it can redesign the power plant so it can still run on coal or natural gas, but without releasing harmful fumes.

Rodney Allam, chief technologist at 8 Rivers Capital, which owns Net Power, says: "The perception has been that to avoid emissions of [carbon dioxide] CO2, we have to get rid of fossil fuels.

"But unfortunately, fossil fuels represent over 70% of the fuel that's consumed in the world and the idea that you can get rid of that in any meaningful sense is a pipe dream."

'Capture ready'

The Net Power system is different from currently operating power plants because carbon dioxide, normally produced as waste when making electricity, would become a key ingredient when burning the fuel.

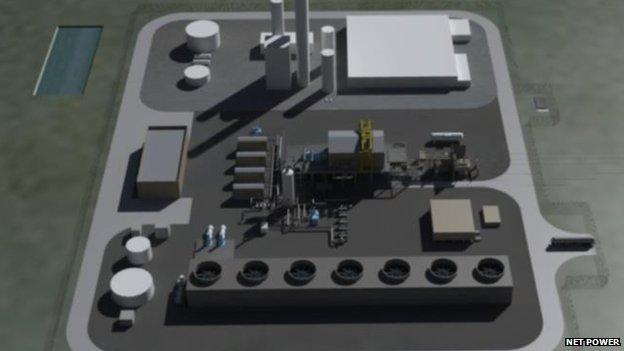

Designers of the Allam Cycle say their model would be cheaper to operate than existing power plants

Carbon dioxide would be put into the Net Power combustor at a very high temperature and pressure along with the fuel, such as natural gas or coal, and oxygen.

Using the carbon dioxide as a so-called working fluid - used to make the turbine function - it would pass through the system in a loop, to be recycled and used again.

Mr Allam says: "I've developed a system where we can actually make use of the impurity itself to try and assist the removal of that impurity from the power system."

In addition, Net Power believes its technology would be cheaper to operate than current power stations.

Mr Allam says: "It was my ambition to create a cycle which would be cheaper - or at least as cheap - as existing technology without CO2 capture, and yet go for 100% CO2 capture."

The system is geared to enable a process called carbon capture and storage (CCS), which would see the excess carbon dioxide from the fuel combustion funnelled into a pipeline or a tanker instead of being released into the air.

The combustor has been built and tested by Toshiba

Mr Allam says that because the whole cycle happens at a high pressure of about 320 atmospheres, the gas emerges with a pressure and level of purity that is "capture ready" - or ideal for storage.

This is different from the carbon dioxide produced by other kinds of power plants, which is mixed with gases such as nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxide.

Separating the carbon dioxide is hard, so it is difficult to apply the process to existing coal-fired power stations.

'Buying time'

Experts agree that although CCS models could be effective, they are still new and need to be proven to work well.

"It would be a good idea to try out the technology and see whether it works, and what it costs," says Prof Dieter Helm at Oxford University.

Meanwhile, Dustin Benton, head of resource stewardship at the Green Alliance, says there is "huge promise" for CCS in the UK.

But he adds: "CCS doesn't solve the emissions problems for the power sector. But if it's cost-effective, it will buy time and help us decarbonise rapidly.

"We don't know what it will cost yet - the promise of CCS mustn't distract us from developing renewables as well."

Net Power says it is planning to build a small power plant that would demonstrate the technology works. They hope to begin construction within the next 12 months.

Their technology has arrived at a moment when the UK is trying to promote low carbon technologies.

The UK's energy sector is in urgent need of investment, but does not have many new projects in place, says Prof Helm.

He adds that by 2015-16 the UK power sector is likely to be under a lot of pressure, as a government programme requiring some power plants to close comes into effect.

The government has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 80% from 1990 levels by 2050.

"There is going to have to be fairly wholesale changes to power as well as transport infrastructure in the UK if we want to meet those targets," says Prof Martin Williams, at King's College's Environmental Research Group.

Mr Benton says this makes the UK a good place to explore the implementation of CCS.

"The UK has a unique combination of [research and development] and offshore engineering expertise, strong, science-led carbon budgets, and an industrial and commercial base that wants CCS to happen," he says.

'Put it underground'

There is still the question of what to do with the carbon dioxide, once it has been captured and stored.

"You can put it straight into a pipeline and deliver it to be disposed of - usually geologically," Mr Allam says. "You put it underground somewhere."

But carbon dioxide pipelines have not been built in the UK yet.

Another option would see the gas put on a ship and taken to the North Sea to be used for a process called enhanced oil recovery, where the gas is pumped deep underground into oil fields where most of the oil has already been extracted.

Because of the way carbon dioxide swells when it mixes with oil, it can be used to push the oil out of places that are hard to reach, getting more out of an existing basin.

But oil emissions are difficult to capture so some researchers say enhanced oil recovery could pose its own environmental challenges.

Mr Benton explains: "CCS might help in the transition to a low-carbon economy, but not if it doesn't reduce emissions overall."

Net Power believes its power plants would be much smaller than the current ones