Hydrogen: The car fuel of the future?

- Published

Hydrogen is combined with oxygen inside this fuel cell to create the electricity to power the car

A small British firm is looking forward to a day in which we will take our cars to the garage and fill them with hydrogen.

Acal Energy, based in Runcorn in Cheshire, says it has developed a chemistry that could make hydrogen fuel cells much cheaper and longer-lasting than current technologies.

It wants to license its chemistry to the world's car-makers, opening the way for hydrogen vehicles to sell in large volumes in 10 or 20 years' time.

"We believe this is one of the breakthrough technologies," says Brendan Bilton, the company's chief commercial officer.

"We're pretty confident and excited... that this will start unlocking the barriers," he continues, "Allowing fuel cells to be in products for mass market applications."

It is a bold dream but not a crazy one.

Persuading customers

The automotive industry is already far advanced with plans for a first generation of hydrogen cars.

Hyundai, the South Korean manufacturer, has said it will soon start selling a hydrogen-powered version of its ix35 model.

Meanwhile, the Japanese giant Toyota is expected to unveil its first nearly-production-ready foray into the territory at next month's Tokyo motor show.

Other big names - including Daimler and Volkswagen - are thought to be on track to get hydrogen vehicles into showrooms by 2017.

But few expect these first-generation hydrogen cars to sell in very large numbers.

Acal Energy is pitching its technology as the enabler for a second generation of less costly, more durable vehicles which could - if all goes to plan - pose a serious challenge to the long domination of the internal combustion engine from about 2020 onwards.

To begin with, consumers may take a bit of persuading.

Hydrogen is widely seen as a dangerous fuel - an image underpinned by that grainy newsreel footage of the hydrogen-filled Hindenburg airship bursting into flames in the 1930s.

But actually, experts do not seem daunted by this particular technical challenge.

'Cheaper than platinum'

They point out that hydrogen is already used and managed on a routine basis in industrial processes.

The main reason anyone bothers with it as a fuel for the future is because it is emission-free at the point of use.

The hydrogen is combined with oxygen in a bit of kit called a fuel cell. This process generates electricity to power the engine in the vehicle.

The waste products are heat and harmless water.

Water is benign, unlike the global warming-inducing, carbon dioxide emissions that spew from even the most efficient petrol and diesel vehicles.

The car industry has been developing fuel cells that use costly platinum as the catalyst for generating power from hydrogen for many years.

Acal Energy claims the problem with this current technology is that it results in fuel cells that are either prohibitively expensive because of the high platinum content, or prone to degrade quickly.

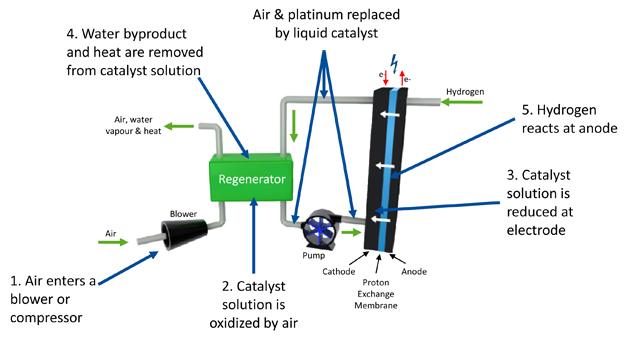

To get round these issues, the company has developed what Mr Bilton describes as a "liquid catalyst" composed of "a dissolved solution of metal salts".

As well as being a lot cheaper than a platinum catalyst, the liquid doubles up as a coolant and a cleaning agent that extends the life of the fuel cell by taking away damaging by-products as it circulates through a "regenerator".

"We have a solution that both increases durability and reduces cost," says Mr Bilton.

Experts say improvements still need to be made for the technology to succeed

Giant chemistry lab

The company has its offices in a science park that until a few years ago was the research and development centre for the British chemicals giant ICI, now shrunken in size and foreign-owned.

Intriguingly, the ideas behind Acal Energy's patented "FlowCath" technology derive from techniques developed to clean clothes more efficiently.

The founder of the company, Dr Andrew Creeth, now its chief technology officer, spent much of his career working as a scientist for the washing powder giant Unilever.

Development of the product is taking place in an environment not unlike a gigantic school chemistry lab - full of bubbling chemicals, complicated equipment and clever looking people in white coats.

The company has already raised £15m ($24m) to finance its work from a mixture of private investors and government sources.

It is currently hoping to raise another £15m or so from a new funding round, with the outcome due to be announced soon.

Eventually, Acal Energy aims to earn profits from the business model pioneered by the successful British micro-chip designer Arm Holdings.

Arm's technology is embedded in most of the chips used in the world's smartphones and tablet computers.

It receives a small royalty payment every time anyone upgrades their mobile device.

Acal Energy dreams of equal success from licensing its technology to car manufacturers in decades to come.

'Improving components'

The big questions, though, are does the technology work and will it be the breakthrough that the company claims?

Andrew Creeth spent part of his career working as a scientist for Unilever

Prof Nigel Brandon of Imperial College in London, a leading academic in hydrogen energy, is well qualified to comment.

"The core technology looks very exciting," he says.

"There are some components in their system they need to improve. I don't see any reason why they can't do that but they've still got to do it," Prof Brandon adds.

It is guarded optimism that could equally be applied to the whole field of hydrogen fuel cell energy.

The big advantages over battery-powered electric vehicles are hydrogen cars can be refuelled in a just a few minutes, they can run for 300 or 400 miles between refuelling and they have the environmental benefits of battery driven cars with the same range and convenience as those with petrol or diesel engines.

But there are also significant snags.

Among them is the need to create a hugely expensive new infrastructure of hydrogen filling stations to replace garages.

Hydrogen enthusiasts often quote the example of the internet.

Once the demand was proven, a global network of optical fibre cables to carry data traffic was rapidly built despite the cost.

Major players in the car industry are betting - but not yet on a truly large scale - that hydrogen energy will follow the same pattern.