What happens in a US debt default?

- Published

Bills, bills, bills: how does the US government pay its debt?

What is a US debt default?

At its most basic level, a default is when a person or an entity cannot repay a debt on time. For instance, when a person can't make a payment on a mortgage or a car loan.

When a country does this, it's known as a sovereign default. This is when the country cannot repay its debt, which typically takes the form of bonds.

So if the US were to default, it would essentially stop paying the money it owed US Treasury bond holders.

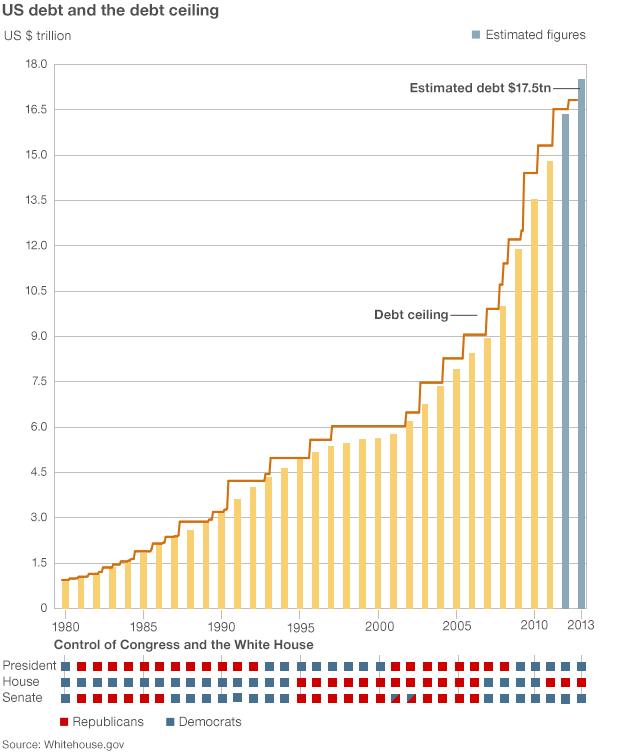

A quick refresher: the US government spends more money than it collects in taxes. So to make up the shortfall, it raises funds by asking investors to buy US Treasury bonds. Investors, such as the Chinese government and pension funds, do this because these bonds are seen as a safe place to invest money.

What are the consequences of a US default?

No one really knows exactly what would happen, but the likelihood is that markets around the world would plunge and global interest rates would rise.

This is because if the US government could not repay the money it owed bondholders, the value of the bonds would decrease. And the yield - the return the government pays to an investor - would rise. This is because it would be perceived as a less safe investment.

This would prompt interest rates around the world, which are often tied to those of US Treasuries, to spike.

Furthermore, the impact on the US's creditors could be dire. Japan, for instance, owns about $1.14 trillion of US debt - which is equivalent to 20% of its annual economic output.

In the US, Goldman Sachs estimates that $175bn would immediately be withdrawn from the US economy and it could lead to a very deep recession.

How does the US government pay its bills anyway?

Strangely, no one really knows exactly how it works.

Each day, the US Treasury receives a little over two million bills from various federal agencies.

According to analysts at Credit Suisse, there are three main offices that pay those bills: the Department of Defense Disbursing Offices, the Bureau of the Fiscal Service and the Financial Management Service.

Technically, the payment systems can be turned on - to make payments - or off - but not much else.

If prioritisation were possible, the US Treasury would probably turn off the tap at the Department of Defense Disbursing Offices and the Financial Management Service. That would leave the Bureau of Fiscal Service, which pays money to bondholders.

What bills does the US Treasury have coming up?

There are quite a few coming up in the next month; the biggest ones are due on 1 November.

After 17 October, the US government will only have about 68% of the funds it needs to pay its bills for the next month, according to a report, external by the Bipartisan Policy Center.

This means that technically, the government could continue to pay some bills.

However, daily revenue intake can fluctuate wildly, making it difficult to plan.

Furthermore, it's not just upcoming bills that could be a source of worry.

Every few days, the US Treasury must "roll over" its current debt holdings - about $300bn in the next month. Rolling over debt is like refinancing a mortgage - it's borrowing money to pay off a loan.

This typically doesn't "cost" anything, as the new debt should directly replace the old debt. But if you can't borrow at the same interest rate, your debt then gets more expensive.

So if investors decide that they no longer want to be involved with US bonds, they could refuse to buy those bonds. And those that are left could demand higher interest rates - which could cost the US government a significant amount in the long run.

Has the US defaulted before?

Not really.

There are three examples in US history that come close to default, with the most recent occurring in 1979.

Then, the US Treasury inadvertently defaulted on $122m, because of what it said was a word processing error.

Although the error was quickly fixed, and even though $122m was a tiny fraction of the $800bn in debt that the Treasury had at the time, a study, external found that the mini-default raised the cost of borrowing by 0.6%, or $6bn a year.

The other two instances, in 1933 and in 1790, both involve defaults akin to the current situation in Greece, when creditors were forced to take less money than what they were owed. Some economists have defined this as a default, but it's murky territory.

- Published8 October 2013