Asia’s parents suffering 'education fever'

- Published

Not sports stars, but Chinese parents seeing off their children to take exams

Zhang Yang, a bright 18-year old from a rural town in Anhui province in China was accepted to study at a prestigious traditional medicine college in Hefei. But the news was too much for his father Zhang Jiasheng.

Zhang's father was partly paralysed after he suffered a stroke two years ago and could no longer work. He feared the family, already in debt to pay for medicines, would not be able to afford his son's tuition fees.

As his son headed home to celebrate his success, Zhang Jiasheng killed himself by swallowing pesticide.

Zhang's case is an extreme. But East Asian families are spending more and more of their money on securing their children the best possible education.

In richer Asian countries such as South Korea and emerging countries like China, "education fever" is forcing families to make choices, sometimes dramatic ones, to afford the bills.

There are families selling their apartments to raise the funds to send their children to study overseas.

'Extreme spending'

Andrew Kipnis, an anthropologist at Australian National University and author of a recent book on the intense desire for education in China, says the amount spent on education is "becoming extreme".

Parents of students starting at Huazhong Normal University sleep in the gym

It is not just middle-class families. Workers also want their children to do better than themselves and see education as the only means of ensuring social mobility. Some go deep into debt.

"Families are spending less on other things. There are many cases of rural parents not buying healthcare that their doctors urge on them... Part of the reason is that they would rather spend the money on their children's education," said Mr Kipnis.

"Parents may be forced to put off building a new house, which they might have been able to do otherwise," said Mr Kipnis who did the bulk of his research in Zouping district in Shandong province, among both middle-class and rural households.

"It can be very intense. They often borrow from relatives. Of course some people have difficulty paying it back," said Mr Kipnis.

A Euromonitor survey found that per capita annual disposable income in China rose by 63.3% in the five years to 2012, yet consumer expenditure on education rose by almost 94%.

Tiger grandparents

It's not just the parents' incomes. Educating a child has become an extended-family project. "It goes beyond tiger mothers, it also includes tiger grandmothers and grandfathers," said Todd Maurer, an expert on education in Asia and partner at the consultancy firm, Sinica Advisors.

There is evidence of high levels of education spending in China, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. Spending is also increasing in India and Indonesia.

South Korean parents bring their children to a smartphone addiction clinic

In South Korea, where the government believes "education obsession" is damaging society, family expenditure on education has helped push household debt to record levels.

According to the LG Economic Research Institute, 28% of South Korean households cannot afford monthly loan repayments, and are hard pressed to live off their incomes.

A huge proportion of that income - 70% of Korean household expenditure, according to estimates by the Samsung Economic Research Institute in Seoul, goes toward private education, to get an educational edge over other families.

Families cut back on other household spending "across the board," said Michael Seth, professor of Korean history at James Madison University in the US and author of a book on South Korea's education zeal. "There is less money to spend on other things like housing, retirement, or vacations."

"Every developing country in Asia, specially China, seems to have a similar pattern," said Prof Seth.

A highly competitive examination system and rising aspirations are often blamed.

"The Korean education system puts enormous pressure on children," said Prof Seth." The only way to opt out of the system is not to have children. It is so expensive to educate a child that it is undoubtedly a factor in South Korea's very low birth rate," he said.

Cram schools

The education obsession is so all consuming that the South Korean government has unsuccessfully tried to curb it, concerned about family spending on extra-curricular lessons and cram schools for ferociously competitive exams.

While not yet at South Korean levels, China's education fever also puts pressure on family spending. A recent survey by market research company Mintel, found that nine out of 10 children from middle class families in China attended fee-charging after-school activities.

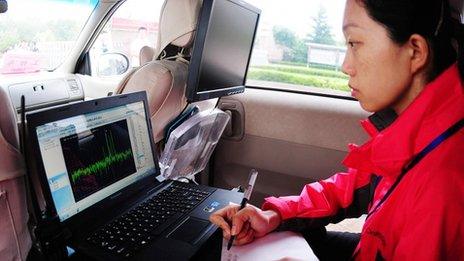

Monitoring radio signals to catch hi-tech exam cheats in Shandong province

Parents believe these activities will help their children when it comes to university entry.

Children are being tutored for longer, starting younger. Where before it was for a year or two before the university entrance exam, now it can start in middle school or even primary.

Matthew Crabbe, Asia research director at Mintel, says that people in China are using the savings that might have been put aside for healthcare.

"But because the cost of education has risen and the competition for places at good universities have become so much more intense, they are investing more of their savings to make sure the child can get the grades they would need to get in."

Massive burden

It does not stop there. Nearly 87% of Chinese parents said they were willing to fund study abroad.

In the past an overseas education was confined to the most privileged. Now many more want foreign degrees to give them a shortcut to success.

According to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a third of Chinese students studying abroad in 2010 were from working-class families.

A fire brigade's personnel carrier is used to make sure a flood does not prevent pupils getting to an exam in Ergun, northern China

This is a massive financial burden and parents may not realise the true costs.

According to Zhang Jianbai who runs a private school in Yunnan province, parents in small provincial cities often sell their apartments to fund their children's study overseas.

"Parents decide very early on that their children are going to go abroad and that requires quite a bit of money because [the preparation] cannot be acquired through the public education system," said Mr Maurer.

It can include intensive English lessons, study tours to the US and significant payments for student recruitment agents.

Last year an estimated 40,000 Chinese students travelled to Hong Kong to take the US college admissions exam, the Scholastic Assessment Test (SATS), which is not offered in mainland China.

Chinese education company, New Oriental Education, organises SAT trips to Hong Kong for $1,000 (£627) on average, and parents spend up to $8,000 (£5,020) on tutoring.

Gambling on results

Once confined to affluent Beijing and Shanghai, it is an expanding market. The company expects its revenue to grow by over 40% in China's second and third tier cities.

Fudan University, Shanghai: Seven million Chinese youngsters graduated this year

"Parents are surrendering their last resources to wager them on a child's future by sending them abroad," said Lao Kaisheng, an education policy researcher at Capital Normal University in Beijing.

It means that when young people graduate there is great pressure on them to start earning.

This is particularly an issue as record numbers of students graduate, seven million this year, and an overseas degree no longer has the status it had in the past. Many graduates languish in non-graduate jobs.

But it is not easy to dampen education fever. In South Korea as in other East Asian countries, "it is deeply embedded in the culture. It's also based on reality that there is no alternative pathway to success or a good career other than a prestige degree, this was true 50 years ago, and it's just as true today".

"As long as that's the case it's actually rational for parents to spend so much and put so much pressure on their children," said Prof Seth.