Giving Richard III a reburial fit for a medieval king

- Published

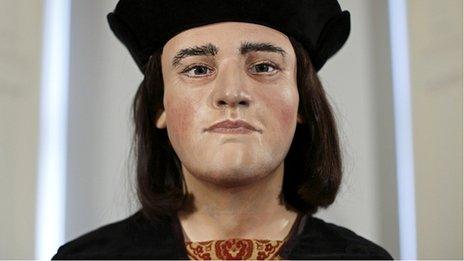

Richard III would have attended such reburial services

The first glimpse of how Richard III could be reburied has been revealed, with the service to be shaped by the scholarly detective work of an Oxford University academic.

Alexandra Buckle, from St Anne's and St Hilda's colleges, has reconstructed how an authentic medieval reburial service should be conducted.

Dr Buckle, an expert in medieval music and liturgical adviser to the committee planning the reburial, has found the only known surviving description of the prayers and music used for reburying medieval aristocrats.

Reburial was a major event in the 15th Century. Dr Buckle says she was surprised to find how widespread it was.

Her research has shown that reburials had their own separate service, different from an ordinary funeral.

This service provides an evocative picture of the medieval world, full of pomp and piety, with prayers that the dry bones being reinterred would be spared the wrathful judgement of God.

'Filthy whirlpool'

Richard III, found by archaeologists last autumn below a Leicester car park, would have attended such reburials in his own lifetime, including for his own father.

And when this last king of the Plantagenet dynasty is reburied next year, with Leicester Cathedral the planned resting place, Dr Buckle's discovery is likely to form an important part of the ceremony.

The bones of Richard III were found below a car park in Leicester

While arguments have raged about where he should be buried and the design of the tomb, Dr Buckle has been establishing how medieval kings would have been reburied.

The reburial service she has uncovered was rich in ritual and elaborate prayers, filled with the language of purgatory and damnation, calling upon God to rescue the reburied person from the "the filthy whirlpool of this world" and to spare them the "savagely burning fire of hell".

In some cases reburial was a practical matter. If an aristocrat was killed in battle he was likely to be buried quickly in the nearest available graveyard - and then later moved to somewhere grander.

Upwardly mobile

But it was also about changing status. Upwardly mobile families wanted to create their own sense of dynastic heritage, so they dug up their ancestors from humble churchyards and put them into more prestigious settings.

As the fortunes of great families increased, so did the scale of the ancestral tombs. It was a form of posthumous social climbing.

"Anyone who was anyone," was involved in reburial, says Dr Buckle, who lectures in music.

A reburial in a great household could take place over two days, with masses, prayers, processions, paid mourners, incense, choirs, and a feast for more than 1,000 guests. The bones would have been sprinkled in holy water before reinterment.

The reburial of Richard's father was accompanied by three sung masses and a banquet where guests dined on capons, cygnets, herons and rabbits.

This was a profoundly religious society and reburial also had an important part in hopes for after death.

"There was a huge preoccupation with the afterlife," says Dr Buckle.

She says that these medieval warlords were keenly aware of their own less-than-saintly lives. They would have been responsible for the deaths of many people, often by their own hand.

Such nobles needed all the prayers they could get. And they left large amounts of money in their wills to be spent on lavish tombs where they would be reburied later.

Alexandra Buckle pieced together the original medieval burial service Pic: Claudia Wilton

"They knew they needed to atone," says Dr Buckle.

Academic sleuthing

The reburial service was part of this spiritual insurance policy. It called for them to be rescued from the "gate of hell" and that the bones would be "re-clothed in flesh" in heaven.

"It was hugely significant what happened after death," she says. The more prayers that were said, the more masses, the more music, were all seen as helping to save their souls.

Once these grand tombs were built, there would be a reburial service, which could be decades after the original funeral.

And Dr Buckle's research has found a template for the words and prayers used in such reburial services, which were carried out from the 14th Century through to the early part of the 16th Century.

Her big breakthrough in discovering the reburial rite came not from an original medieval document, but from a much later copy, lying unrecognised in the British Library.

Many original medieval manuscripts have been lost, not least because they were made of expensive material that was reused.

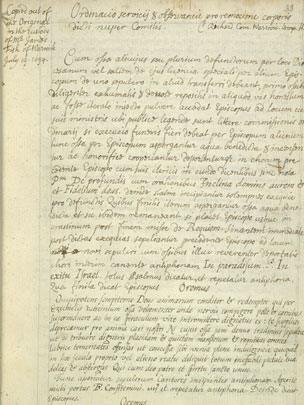

The medieval manuscript is lost but the copy made in the 17th Century has survived Pic: British Library

But a 17th Century scholar and librarian, Humphrey Wanley, had painstakingly copied medieval manuscripts and translated them from Latin into English.

Among the the copies made by Wanley was a transcription of the reburial service and music, used within about a decade of the death of Richard III. Dr Buckle came across this copy while researching another 15th Century noble and realised its significance.

'Dust to dust'

This is the only known surviving version of such a medieval reburial service.

"We can be quite clear that we're dealing with a good copy because he was such an eminent copyist," she says.

The wording showed that this was a general rite, rather than a one-off service. It was structured so that the name of a person could be inserted into the text, marked with the letter N, the Latin "nomine" for name.

The prayers, which would have all been in Latin, focus on dry bones, rather than a body.

They call upon God to "bind together truly dry bones with sinews, to cover them with skin and flesh, and to put into them the breath of life".

The words of the service pray for the "bones we transfer today to a new tomb, so that the shade of death not control him nor chaos and the darkness of shadows cover him".

There are prayers not previously known before. But there are also familiar phrases, such as "ashes to ashes, dust to dust".

The service also calls for eternal rest in words still used in prayers for the dead: "Let perpetual light shine upon them." Dr Buckle says this gives a sense of continuity back to medieval, pre-Reformation England.

The document includes details of several specific psalms and antiphons that were to be sung and from other surviving manuscripts it's possible to reconstruct how they would have sounded.

Dr Buckle says that this template for a reburial service is a way of finally giving Richard III a fitting send-off, in a form that would have closely resembled the prayers used when he reburied his own father.

Richard seemed to be a religious man, his devotional books have survived with his own notes in the margin. And Dr Buckle believes he would have expected such a religious service.

"We know Richard III had a very meagre night-time burial, probably just a basic requiem. He was covered in wounds, probably not embalmed.

"There may have been a shroud, but there is no trace of it, or he may have been buried naked, as it shows how rushed this was."

His body was treated with little dignity after his defeat in battle and his burial place was neglected for many centuries.

"This will give him the funeral he never had," she says.

"And the focus should be on how he is buried, not just where."