Young and jobless forever: What do the numbers tell us?

- Published

Unemployment rates can hide many of the realities faced by those in work

The jobs crisis facing the world's young people shows no sign of abating. The evidence suggests that queues for jobs are growing longer and some are getting so frustrated at their employment prospects they have taken to the streets to protest.

The statistics can make gloomy reading. If you group together the European Union and other developed economies, the youth unemployment rate has risen by a quarter since 2008.

But headline figures do not tell the whole story of the situation facing many of the world's young people today.

A year ago I examined the work prospects for young people, pointing out some of the idiosyncrasies in the way the statistics are calculated.

Twelve months on, the situation is no more promising. In fact, according to the United Nations' International Labour Organization, external (ILO), the situation for young people will continue to worsen until 2018.

"It is not a good time to be a young person looking for a job," the ILO's Theodore Sparreboom says bluntly in one of the organisation's videos.

The ILO estimates that in 2013, more than 73 million young people - those aged between 15 and 24 - are out of work, a global rate of 12.6%.

The eagle-eyed will notice that this appears to be lower than last year's figure, which was originally 75 million, but has since been revised down as the real data became available and the ILO adapted its sophisticated econometric models.

Young and jobless trail

Who are the young and jobless?

Before taking a closer look at the numbers in particular countries, we have to understand how they're arrived at.

All unemployment rates are calculated as percentages not of the total population, but of something called the "economically active population". That is the employed plus the unemployed, which have strict definitions so that we can make comparisons between countries.

Someone is classified unemployed if they do not have a job but would like one, have actively looked for one and have the time to do it.

A person is "economically inactive" if they neither have a job nor are unemployed according to the definition above.

It could be that someone does not want or need to work so hasn't actively sought out a job, or it could be that someone is unavailable to work - for example, as is likely with young people, they are studying full-time.

Is there a gender gap?

Relying on statistics alone can hide a far more complicated picture. For example, a young person's sex can make a big difference to their employment prospects.

"If you are a young male you have a higher chance of finding a good and stable job in developing countries," says Sara Elder, a senior economist at the ILO.

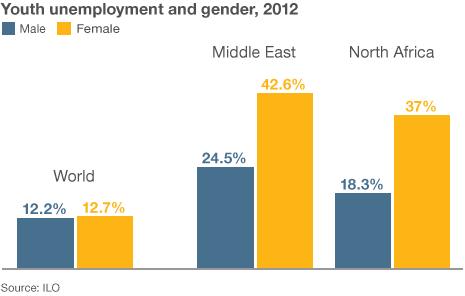

The difference is startling in some countries. Take the regions with the highest youth unemployment rates - the Middle East and North Africa. The unemployment rate for young Middle Eastern men was estimated to be 24.5% in 2012. For young women, it's much higher, at 42.6%.

In North Africa too, young women are twice as likely to be unemployed as their male counterparts.

What does irregular employment mean?

Unemployment rates can also hide many of the realities faced by those who are in work.

When you compare high-income economies to some of the least developed countries, "big differences are found in the regularity of work", explains Ms Elder.

"Very few young people in the least developed economies can find a job with a contract that goes beyond 12 months."

In developing countries, six in 10 young people are engaged in irregular employment: a salaried worker with a contract of less than a year, a self-employed young person with no employees and contributing family workers.

The figure for high-income economies was fewer than two in 10.

And there is a strong link between the proportion of young people in irregular employment and the proportion in informal employment - where people are either working in the black market or are working in the formal sector, but without entitlements to sick pay, paid annual leave and social security.

Across 10 countries analysed by the ILO, the proportion of young people working informally is as many as eight out of 10.

Does education distort unemployment figures?

Using a strict definition of unemployment can also help give a misleading picture of the plight of the young.

In developed economies, many people remain in full-time education into their twenties. This means that the economically inactive population is very large in relation to the economically active and high youth unemployment rates can be the result.

If we revisit the two EU countries which featured last year, Spain and Greece, they both had youth unemployment rates higher than 50% , externalin 2012 - increases on the year before.

If we try to account for the effect of remaining in education by calculating the ratio of young people unemployed - the share of people without a job as a percentage of the whole youth population - the prospects for young people perhaps do not look quite as stark. The proportion "unemployed" in Spain now falls to just over 20%.

In other areas of the world, using a strict definition of unemployment has the opposite effect: it hides a more worrying reality.

Remember that to be counted as unemployed someone has to be actively looking for work.

In most developed economies, it makes sense for young people to search. They have to prove that they've been trying to find a job in order to receive unemployment benefits.

But in developing countries, where no such benefits exist and poverty forces young people out of school and into the workplace, it makes less sense.

If we relax this "active job search" requirement, it has a significant impact. In some of the least developed countries the unemployment rate more than doubles.

Unemployment continues to be a huge obstacle to millions of young people in scores of countries across the world.

What is perhaps more worrying is that because of the way joblessness is calculated, the crisis could be even worse than the raw numbers suggest.