Big infrastructure projects: Before and after

- Published

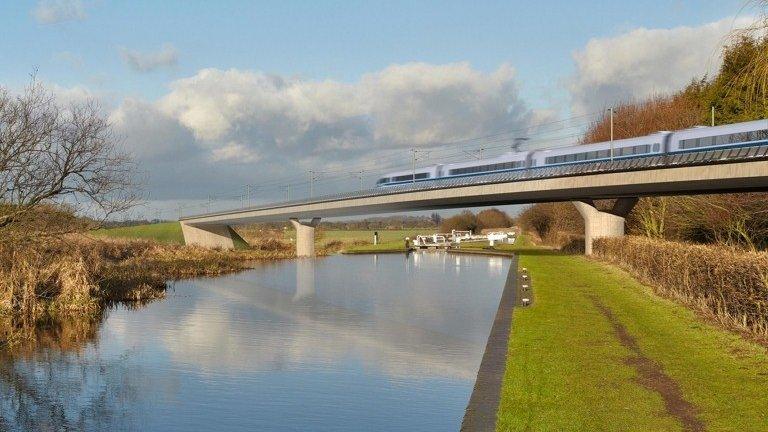

HS2, the high-speed rail project designed to shorten journey times between London and the Midlands and the north of England, has attracted much opposition from those who say it does not offer value for money.

The cost of the project is currently estimated at £42.6bn.

Commentators, investors and ordinary members of the public often offer some scepticism when they hear that the government is planning to invest billions of pounds in the hope that it will generate more money back over the long-term. They are also sceptical that projects can come in on budget and on time.

But is that scepticism unfair? Of the big infrastructure investments that the government has put money into over the past few decades, have they proved value for money and run to plan?

Channel Tunnel

The Channel Tunnel was undoubtedly one of the grander transport projects in recent British history. Mooted since the 1800s, it was not until 1986 that the agreement between the British and French governments was signed into law and passenger traffic got under way eight years later.

The project transformed travel from London to Paris and Brussels and has been considered an overall success with more than 300 million passengers using the tunnel while some 34 million tonnes of freight has been transported.

But it was not without its problems. By the time the first passenger hopped across La Manche, the original business plan was in tatters.

For a start, it was one year behind schedule. Worse, it was some £2bn over budget.

A higher-than-expected cost of digging the tunnels and lower-than-expected tunnel traffic levels meant that the company Eurotunnel was left laden with massive debts. This eventually led to a French court having to grant it creditor protection, before the company reorganised and had its debt restructured.

Initial British and French forecasts estimated around 17-20 million passengers per annum. Instead, figures have ranged between 6-7 million in 2004 and 9-10 million today.

Eurotunnel told Parliament that only 50% of the passenger capacity was used, external, with only about 10% utilisation for freight.

David Freud of investment house Warburg, which sold Eurotunnel shares, said: "The traffic forecasts were not just out by a little bit. They were completely potty."

Meanwhile, the Public Accounts Committee suggested that the Department for Transport failed to anticipate that airlines and ferry companies would adjust their pricing, external so as to compete with the tunnel.

HS1

Britain's only other foray into high-speed rail has come in the form of HS1, the stretch of line which runs from the Channel Tunnel up through Kent into St Pancras station.

HS1 decreased the journey time from London to Paris considerably and it was also finished on time. It has also dramatically improved journey times for thousands of commuters from east Kent into London, reducing a trip that would once have taken nearly one and a half hours to some 37 minutes.

However, the National Audit Office has estimated that the total cost to taxpayers of supporting HS1 could be £10.2bn up to 2070 and that the value of journey time savings will only be £7bn in the same period. More than £3bn in deficit.

The National Audit Office has said:, external "The HS1 project has delivered a high-performing line, which was subsequently sold in a well-managed way. But international passenger numbers are falling far short of forecasts and the project costs exceed the value of journey time-saving benefits."

In another sense it is even more difficult to assess whether the scheme has been worthwhile for Kent. There has not been any comprehensive study as to how or even if the line has had any net economic benefit for the county, as Radio 4's File on Four reported recently.

Also, while some commuters can now get to work faster, others in east Kent have seen their quicker journeys reduced. Their trains now have to stop at more stations because capacity has been reduced in the name of the newer high-speed trains which do not stretch to the eastern side of the county.

Jubilee line extension

The Jubilee line is London's newest tube line and its extension is the most recent major upgrade in the network's history.

The extension to the Jubilee line was recommended in the East London Rail Study in 1989 with Royal Assent to the Bill obtained in March 1992. Work started on the project in December 1993 and then opened in 1999.

Initially the project was forecast to cost between £2bn and £2.5bn. In the end it cost £3.5bn. Where initially the developers were to make a significant contribution to the extension, their final contribution was less than 5%.

However the project clearly had an impact. One Oxford University study, external in 2007 estimated total property value increase around Southwark and Canary Wharf Stations was more than £2.1bn (above inflation) and this could be solely attributed to the impact of the extension.

The government estimates that the project cost the taxpayer some £6bn in initial costs and maintenance but has generated around £10bn of economic benefit.

HS2

So where does that leave us with attempting to assess whether HS2 is value for money?

It is undoubtedly the case that national (or even international) infrastructure projects are prone to cost overruns and can be waylaid by bureaucratic problems.

But it is also clear that the amount of economic growth generated by infrastructure is very difficult to predict and measure.

Huge infrastructure projects like HS2 alter the behaviour of individuals and businesses for years and generations to come. It is pretty tricky to put a net benefit on that.

For example, how could you begin to assess the economic contribution that London's first underground service, the Metropolitan line, has made to the capital in the 150 years of its operation?

By contrast, measuring their cost is relatively easy and thus some projects never get off the ground as groups opposing them have more political ammunition to fire.

As Dan Durrant of University College London has argued,, external we might need a better and more holistic way of thinking about the benefits and costs of such projects.

The more that supporters of schemes use older, traditional cost benefit analyses, the less likely they will be to convince policymakers and members of the public alike.

New methods

There have been some new stabs at measuring the long-term economic benefit of infrastructure. For example, The Greater Manchester Transport Fund (GMTF) is a pot of money put together by the different councils of Greater Manchester which allocates transport investment worth £1.5bn.

They use very different criteria for assessing investment than the Department for Transport. Potential projects have been modelled to account for their potential impact on GVA (Gross Value Added), employment and productivity, as well as reductions in carbon emissions.

Interestingly, this new method produces very different outcomes. Indeed the scheme which ranked first under this so-called "real economy" approach came only ninth using traditional methods.

Countries such as Ireland, Spain, Finland, Canada and Japan employ multi-criteria analysis systems, whereby a form of weighting is used to balance the impact of individual criteria within an overall assessment.

By comparison, the UK's methods are quite limited and occasionally labelled inadequate. For example in a recent review of 189 impact assessments, the National Audit Office judged that 44% of appraisals were not fit for purpose, external.

So HS2, like all infrastructure projects, is a gamble. The truth is that both supporters and opponents cannot be sure how much it will cost or how it will affect customer behaviour and economic growth over the long-term.

But what might help the debate is another look at just how those pluses and minuses are assessed and, when a project has been completed, a closer look at just what its benefits have been against its costs.

That way the next time another big transport project comes along we might have more confidence in declaring "full steam ahead".

- Published29 October 2013

- Published28 October 2013

- Published27 October 2013

- Published19 October 2013

- Published8 October 2013

- Published24 September 2013

- Published6 October 2023