The world's insatiable hunger for phosphorus

- Published

Is it the biggest looming crisis that you have never heard of?

Since 1945, the world's population has tripled to seven billion, and feeding that population has relied increasingly on artificial fertilisers.

Phosphates, among the most important fertilisers, come from an ore that is in limited supply. It is mined, processed and spread on to our fields, whence it is ultimately washed away into the ocean.

So what will happen if one day we run out of the stuff?

"Crop yields will drop very, very spectacularly," chemist Andrea Sella, of University College, London, told Wednesday's Business Daily programme on the World Service.

"We will be in very, very deep trouble. We have to remember that the world's population is growing steadily, and so demand for phosphorus is growing every year."

As Dr Sella explains, phosphorus is essential for life. The element - which is so reactive that it spontaneously combusts in its pure form - is used by plant and animal cells to store energy.

It also forms the backbone of DNA, and it is an essential ingredient of our bones and teeth.

Farming without it is not a realistic option.

Underpriced and undervalued

While this may sound rather alarming, there are two important caveats.

First, the supply of phosphates is forecast to last for many decades, if not centuries, to come, external.

So humanity is at no immediate risk of running out of the means to feed itself, even at the current rate at which it is gobbling up phosphates.

Second, one of the biggest problems with phosphates over the past 60 years is arguably that they have been far too cheap and abundant.

There has been no incentive to use them sparingly.

Only a small fraction is actually absorbed by plants, and much is washed off by rain.

And this glut of fertilisers being washed into river systems, both phosphates and also nitrates, has created a nasty environmental problem - eutrophication.

This is where the abundant nutrients feed algae in rivers and ponds, creating blooms that turn the water green.

The algae then die, providing a feast for microbes, which in turn multiply and suck the oxygen out of the water, killing off all the fish and other animal and plant life.

It is a common problem in the lower reaches of major rivers such as the Thames, external and Rhine in Europe, and the Yangtze in China.

Similar algal blooms occur in our oceans, where large areas - notably the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Mexico - have become "dead zones".

Fertiliser run-off encourages the growth of algal blooms at sea

Purely from an environmental perspective, the price of phosphates has clearly been too low.

'A hopelessly bad system'

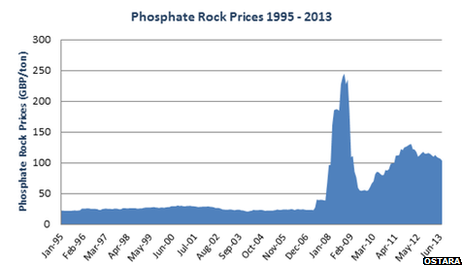

Yet this now appears to be changing. The price of phosphate ores has risen fivefold over the past decade as demand, particularly from the developing world, has grown steadily.

Meanwhile, the cost of fertiliser production has also risen as the richest, cheapest phosphate seams have already been mined.

The smell is driving away beachgoers

"Commodities are priced on the cost of extracting the next tonne that you need," says Jeremy Grantham, of US fund managers Grantham Mayo van Otterloo. "It is a hopelessly bad system.

"As long as we can mine a vital resource cheaply, we will price it cheaply, and run through the reserves until they become very expensive. And then we'll start to conserve."

There are various options:

Modern agriculture could start using phosphates far more sparingly and capture what is currently washed away

We could breed or genetically engineer crops that are more efficient in how they take up phosphorus, external, and so need less fertiliser

We could regulate - for example, the European Union recently banned another common usage of phosphates, external in cleaning products where it is used as a water softener

Where there's muck there's brass

And then there is the sewage option.

Why not just capture the phosphorus from our own waste and recycle it? Sweden and Germany have been leading the way.

UK water company Thames Water is now extracting phosphate from sewage waste

There is also a cottage industry among the eco-friendly in Western countries of "compost toilets".

Now the UK's Thames Water is getting in on the act, launching a new "reactor" that turns sewage sludge into nice clean fertiliser pellets, external.

How much of future supply could ultimately be provided by recycling is open to debate - Thames Water says 20% using the current technology.

But perhaps the more important point lies in the fact that Thames Water and Canadian partners Ostara, which developed the technology, expect to make a profit.

This should come from selling the pellets as well as from saving the cost of cleaning and replacing pipes that have become blocked by a phosphorus-based sediment called struvite.

Any benefits, as far as the environment or the long-term sustainable usage of a limited resource are concerned, are but a happy by-product.

The important point is that it is the rising price of phosphates that has made it worthwhile to start recycling the stuff.

A beautiful friendship?

So should we welcome the higher price? Well, it depends who you are.

In general, the lower your income, the more of it you spend on food and therefore the more sensitive you are to the higher food bills that might come with more expensive fertilisers.

In other words, rising phosphate prices hurt the poor most, which is hardly a recipe for social cohesion.

And that goes for whole countries too.

As Jeremy Grantham points out, many North African countries depend on food imports, and rising food prices contributed to the discontent behind the 2011 Arab Spring.

One of those countries is Morocco, which by a freak of geography controls about three-quarters of the world's remaining good-quality phosphate reserves.

"Morocco has the most impressive quasi-monopoly in the history of man," says Mr Grantham. "It makes oil look unimportant in comparison."

That could make Morocco a very rich nation in the future, one that the rest of the world will be keen to court.

And it gives the country a great responsibility in pricing its product in a way that eventually weans the world off it in a manageable way - much like Saudi Arabia and oil.

Ironically, the higher prices that monopolists like to set may actually be what the planet needs.

Strategic questions

But Morocco's unique position could also make it a centre of intrigue.

For example, much of its phosphates are actually located in the territory of Western Sahara.

It is occupied by the Moroccan military, which currently has an uneasy ceasefire in place with the local Algerian-backed Saharawi resistance.

Morocco controls 75% of known global quality phosphate reserves

This poses moral questions for the multinational companies that mine the stuff there, external, as well as some obvious strategic issues for the rest of the world about securing future food supplies.

Mr Grantham points out that half of nearby Mali - admittedly the sparsely populated Saharan half - was recently briefly overrun by militants affiliated with al-Qaeda, and he warns that Morocco itself may one day become the scene of rising social tensions, terrorism or revolt.

"I would almost guarantee to you that the major militaries of this world are well aware of this problem.

"They would not allow Morocco to become a hopelessly failed state," he says reassuringly.

"You don't want to look forward to the great fertiliser wars of 2042."

You can listen to Business Daily on BBC World Service at 08:32 GMT and 15:06 GMT.