Can UK economy stay top of the league?

- Published

- comments

Why is the British economy like my favourite football team, Arsenal FC? We're both top of the league - by a margin (blimey, it's been a few years since I said that).

If the latest Markit survey of business activity and orders is accurate, the British economy is growing at a remarkably rapid 1.3% in the last three months of the year - which would be faster than any other rich developed economy.

The UK is growing significantly faster than Germany and the US, for example - and probably faster than Japan, which in my strained analogy is Liverpool FC, whose under-performance has endured even longer than Arsenal's.

If that estimated British growth rate is accurate and sustained, UK GDP in 2013 will rise over 3% - which is significantly faster than any mainstream economist is currently predicting and would be a return to growth rates we haven't enjoyed since the financial and economic crash of 2007-8.

So the question about the British economy is the same as the question about Arsenal. Is the current success built on solid foundations - it it sustainable?

Probably the first thing to say, if you're an Arsenal supporter or a British citizen, is that any recovery will do, after six bleak years (longer for the Gooners).

But the worry would be that the economy and Arsenal are a bit thin in defence and attack.

What do I mean?

Well, after the election, the hope of the government was that this would be a recovery different from all others in modern times, one led by exports and business investment, in order to reduce the UK's economic dependence on debt-fuelled consumer spending and economic activity linked to a booming housing market.

To use the ghastly jargon, the economy would be rebalanced, so that we would gradually reduce the deficit between what we buy from the rest of the world versus what we sell abroad - a deficit that has put the debts of the UK on a rising trajectory for 30 years.

It was a bit like the hope of Arsenal that it could win the Premier League without spending record sums on world-class players, or paying those inflated wages of more than £100,000 a week.

Well, business investment plummeted in 2008 and has never properly recovered. And the gap between exports and imports has remained stubbornly wide.

In fact in the first three months of the year, the UK's deficit with the rest of the world was a shocking 5.5% of GDP, before narrowing to a still too-wide 3.2% in the second quarter.

The result has been a failure by the UK to restore economic output back to where it was in early 2008, which has contributed to a painful and persistent squeeze in living standards.

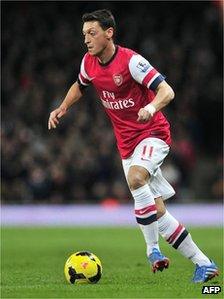

Expensive signing Ozil in action

And there has been an analogous absence of any trophies in the Emirates' cabinet, as a consequence of a policy decision not to splash the cash on superstars.

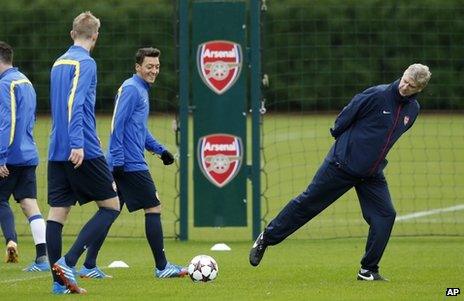

But 2013 has been a year of modest ideological shift (should we say U-turn?) by Wenger and Osborne.

Arsenal's Wenger relented and forked out £42m for the balletic and brilliant Ozil, and has allegedly smashed through the wage hierarchy at the club in the process.

And the British chancellor belatedly concluded that it was highly unlikely that the UK economy would gain what economists call "lift-off momentum" without the traditional boost to the morale of British consumers from a reviving housing market. So George Osborne launched versions one and two of the Help to Buy scheme, which provides many billions of pounds of taxpayer loans and guarantees for house construction and house purchases.

Here is the thing. Respective revivals based solely on a few star midfield players or on debt-fuelled consumption would end in tears.

So can the recoveries be underpinned - in the case of the economy, by businesses belatedly starting to invest and getting better at selling to the rest of the world; and at Arsenal, by reinforcement of defence and attack in the January transfer window?

And here the football analogy implodes.

Arsenal can afford to invest in new players having been prudent in the way it has managed its finances in boom years and lean years.

By contrast, the UK economy is still shouldering record and rising debts, equivalent to more than five times the value of economic output (based on aggregating household, business, financial and government debts).

Which means that the British economic recovery could be self-immolating in a way that I don't think could happen to Arsenal.

What do I mean? If the Bank of England became concerned that the speed of growth was becoming inflationary, it could push up interest rates much faster than is currently implied by its so-called "forward guidance" on this.

And with household liabilities still equivalent to some 140% of household resources, and with an estimated five million households shouldering excessive debts, sharp rises in interest rates would cause profound misery.

That misery would not be confined simply to people. It would also infect our banks (again), which would suffer significant losses as borrowers discovered that they could not afford to pay interest rates above today's abnormally low rates.

So if you think there's pressure being Osborne or Wenger, it is probably as nothing compared with the burden on the Canuck governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney.

If he and his colleagues raise interest rates too soon and too much, there's a risk the recovery will be suffocated at birth, or worse. Were he to raise them too late, there is a danger that the financial precariousness of households and banks would actually be worsened, as they ship in more debt - and the anti-inflation credentials of the Bank would be undermined, perhaps fatally.

Now what would Alex Ferguson have done?