Can spending millions on art ever be a good investment?

- Published

Three Studies of Lucian Freud is the most expensive artwork sold at auction

Consider the idea of spending $142m (£89m, 106m euros) on a work of art and then being told you have bagged a bargain.

A number of art critics have said that the price paid for Three Studies of Lucian Freud (1969), by Francis Bacon, is money well spent.

While the anonymous new owner decides how to insure and where to hang the triptych, stretched householders may wonder how a purchase like this could ever be a good deal.

And should they decide to invest in art themselves - at a less spectacular level - then there are warnings that the value of such items can go down as well as up.

Crisis? What crisis?

The Bacon masterpiece became the most expensive artwork ever sold at auction when it went under the hammer after six minutes of frantic bidding.

Calculations by The Economist, external suggest that Van Gogh's 1890 work Portrait du Docteur Gachet actually cost more at auction if inflation is taken into account. The $82.5m paid for that painting in 1990 is the equivalent of $148.6m at today's prices, the magazine says.

Meanwhile, in 2011, the Qatari royal family paid more than $250m for a Cezanne in a private sale, The Economist adds.

All the same, $142m is an eye-watering amount of money, even though there are three paintings in the set, and especially as we are only slowly emerging from a global financial crisis.

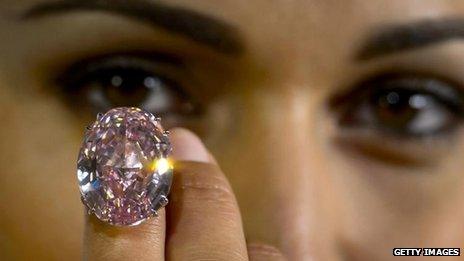

The Pink Star was sold for $83m at auction in Geneva

A total of £782m was spent during the Christie's auction of post-war and contemporary art that night.

On the same day as the Bacon sale, a diamond known as the Pink Star sold for $83m (£52m, 62m euros) at auction in Geneva - the highest auction price for a gemstone.

"At the moment people wonder how come art is securing such funds," says art critic Estelle Lovatt.

"When you consider interest rates at the banks at the moment, your money works much better and the result looks much prettier on the wall or on a plinth.

"It has been an incredible year [for art sales], especially given the financial situation.

"Some people say it is vulgar to talk about art and money at the same time - cash is the C-word in the art world. But it is a great investment."

Or is it?

Top v bottom

Just a few hours after record-breaking sums were being bid in New York and Geneva, a watercolour work called Portrait of a Lady was sold for £238 at an auction in Edinburgh.

Another watercolour entitled Flower Arrangement went under the hammer for £275, and the top sale of the day was a mahogany bookcase that fetched £18,750.

Auctions such as this are taking place across the country most days of the week, buoyed in part by the popularity of daytime TV auction shows such as Antiques Roadshow and internet auction sites.

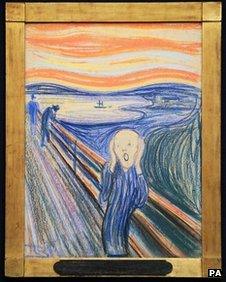

The Scream by Edvard Munch could have been yours for £74m

Yet, it is a two-pace market, according to Richard Madley, a fellow of the National Association of Valuers and Auctioneers (NAVA).

"It is akin to the London housing market compared to the rest of the UK, where prices go up and up in the capital," he says.

"A work by Bacon is like an eight-bedroom house in Belgravia, while the chest of drawers is the two-bedroom cottage in the North East which remains affordable," he says.

While the global super-rich keep spending record-breaking amounts at the top end of the market, prices of domestic, lower-value antiques have tumbled, he says.

For example, last year, $119.9m (£74m) was paid for Edvard Munch's The Scream, whereas in the last 10 years the typical price of a traditional dinner service or a Victorian wardrobe has halved.

The reason is that masterpieces will usually retain their appeal, while lower level furniture and art are at the mercy of fashion.

"Antiques are not cool. Young people in their 30s and 40s do not want what their parents hung on the wall; they do not want a big Victorian extending dining table; they want glass and chrome," Mr Madley says.

Chinese lesson

Anyone considering taking the risk of investing could look for a lesson in the market for works from China and Japan, according to auctioneer Mr Madley.

Bidding for Japanese porcelain hit its height in the 1990s but prices have fallen since.

Yet, as disposable income rises in China, the new middle class and wealthy are buying back the heritage that left the country in decades past. Chinese ceramics, bronzes, jade and metalwork are proving particularly popular.

In one case, Mr Madley says, a Chinese pottery bowl that had a reserve price of £200 sold for £37,000. A lot such as this is known as a sleeper, which is awoken by frantic bidding.

Anyone thinking of buying at auction for the first time should ask for help before the bidding starts, Mr Madley suggests, and they do not need to worry that scratching their nose could be mistaken as a bid and cost them thousands of pounds.

"Auctioneers look for serious bidding signals, and bidders now are often given a piece of paper with their number on when they register," he says.

Other tips include:

Have a look around on preview days, talk to the auctioneer, and pick up a catalogue

Look at the guide price. The minimum amount that the seller will accept is confidential, but cannot exceed the lower estimate

Watch an auction first, before taking part

Remember the extra charge, known as a buyer's premium. It can vary from 5% to 25% of the bid price. Ask about the cost beforehand

The most important advice when buying art, according to Mr Madley, was a tip he was given as a young man by one of his bosses.

"Buy art with your eyes and not your ears. It must give you pleasure to look at it, don't buy it because someone tells you it will be worth more in a few years' time," he says.

Still, ask anyone who was at the auction of the Bacon triptych last week, and they will say that as the bidding hit stratospheric levels, they could believe neither their eyes nor their ears.

- Published14 November 2013

- Published13 November 2013

- Published31 August 2010

- Published3 May 2012

- Published13 November 2013