Why IT failures at big companies are unlikely to go away

- Published

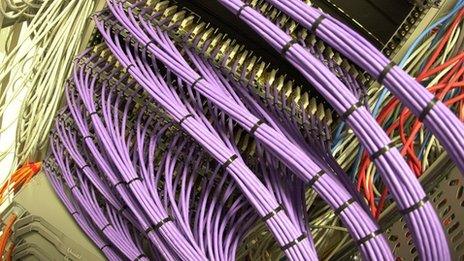

Computer system failures are depressingly common

Business deals that have to be aborted, staff who don't receive their wages, invoices that don't get paid on time - companies can face potentially catastrophic disruption when their banks suffer computer system failures.

Yet these interruptions are far from uncommon - institutions like NatWest, Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds and many others have all run into problems that have left their customers in the lurch, and their IT staff scrambling to find and fix the issue.

Of course it's not just banks that suffer technology failures, sometimes it's organisations that most people have never heard of, and these glitches too can have a big impact on businesses and individuals.

In the height of the summer, for example, the Sabre reservation system used by more than 300 airlines crashed for several hours, resulting in flight cancellations and delays, with some airline staff resorting to paper and pen to check in passengers manually.

So why do these important systems crash so often? In fact why do they crash at all?

'Risk reward balance'

It may often come down to money: eliminating software bugs and other system weaknesses is expensive, and as organisations eliminate the lowest hanging fruit they get progressively less benefit from spending more.

"How much money you are prepared to spend is based on the relative risk of what happens if you don't," said Simon Acott, director of IT services company exponential-e at a recent event hosted by lawyers Pinsent Masons.

"You have to find the balance between the risk and the reward."

System failures at banks can cause substantial disruption for customers

This type of bug-catching economics is also the reason that relatively cheap consumer software is often prone to locking up or crashing the computers it runs on.

Making the software more reliable would undoubtedly be possible, but to do so the developers would have to invest so much more time and money that the price of the product would end up having to be unacceptably high.

The result is that companies often produce software that is "reliable enough", and that can be sold at a price that appeals to the mass market.

'Not enough tests'

But what about the systems that banks and other large companies use, and that millions of customers rely on? Surely it is worth these organisations spending substantial amounts to ensure that the technology that they are using is not faulty?

Damien Saunders blames people rather than technology for most systems failures

"I take a contentious view and say that IT outages are rarely to do with technology," says Damian Saunders, a cloud networking director at Florida-based virtualisation and software company Citrix Systems.

"There's normally a role that technology plays in the outage, but when I look at the root cause, by far the greatest cause is people and processes."

What does this mean? In some case it can be as simple as staff not sticking to the rules that have been established for testing new software before it is actually put into service.

Organisations may have a well thought-out policy that requires software to be tested 10 times, but that doesn't help if staff don't actually carry this out.

"If you do nine tests out of 10 and then say, 'We have done nine, the 10th will be OK,' then you could have problems," says Andrew Marks, chief information officer at London-based oil and gas exploration company Tullow Oil. "Often the 10th test is the one that lets you down."

'Old technology'

When it comes to banks, though, there's a more fundamental reason why the IT systems are prone to failure, according to an IT development manager at a large lender in London who talked to the BBC on condition of anonymity.

"Banks are old, and the technology that they use is old, and there are fewer and fewer people around who know how to keep it running," he says.

In many cases banks are using "buggy", out-of-date versions of software instead of more recent releases, because they don't know what the effect of updating the software will be on other systems that it interacts with, adds the IT development manager.

Many large companies outsource the management of their computer systems

"Twenty per cent of the systems that we run in our bank use 'out of life' technology which is no longer supported by the vendor. You can't blame the software for failing because in many cases if we had upgraded it, it wouldn't fail."

Faced with the decision to upgrade these systems - with all the risk and cost that that would entail - or leave them alone, many banks choose to outsource their management to third party companies and wash their hands of them, he says.

But, he says, it is even harder for the third party companies to keep the systems running reliably.

"When you outsource you lose all the subject matter expert knowledge, so it takes three or four times more people to keep the systems running. And in some cases they have no idea what the software they are responsible for actually does because nobody does any more."

The result is a larger team of staff that has to be managed, and more people accessing the software code. "This can have huge negative ramifications in terms of reliability," points out the IT development manager.

'Rebalancing project'

But Kerry Hallard, chief executive of the National Outsourcing Association, rejects the idea that outsourcing is partially to blame for banking system failures.

Simon Acott says firms don't want to spend a fortune on improving their software systems

"More often these days outsourcing is to add value and increase skill sets, not decrease them," he says.

"If you find you are outsourcing and need more people and lose critical skills then you are doing outsourcing wrong."

However, the bank IT development manager believes the way to improve the reliability of bank systems is to develop and maintain more skills within the banks themselves so that systems can be modernised.

But that would also entail bringing many outsourced systems back in house - a rebalancing project that he thinks is unlikely to happen in the current economic climate.

"It's depressing because it's only if that happens that will we see the issues we face being stabilised, and ultimately a reduction in the number of catastrophic bank outages," he concludes.