Bank fines go to good causes after rule change

- Published

The coalition wants charities to benefit from the misdemeanours of bankers such as Javier Martin-Artajo (l), alleged mastermind of the "London Whale" scandal

Most reasonable observers would count over-zealous bankers as one cause of the financial crisis that sparked a global economic downturn, wiping billions off corporate and government balance sheets alike.

But there has been a small recompense (with the emphasis on small).

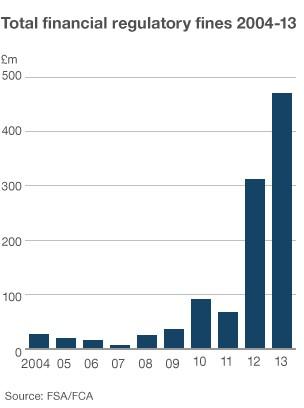

Monies coming back from financial institutions in the form of fines from the regulator have rocketed in recent years, with almost £500m handed out in penalties by the Financial Conduct Authority - and the Financial Services Authority before it - this year alone.

This compares with just £5m in 2007, the year before the financial crisis really took hold.

Dodgy dealings within the City are the main reason for the dramatic increase.

This year the regulator has penalised Rabobank and Royal Bank of Scotland to the tune of £193m for attempting to rig Libor - the crucial interbank lending rate that is a key benchmark for interest rates across the economy.

In 2012, Libor fines from UBS and Barclays totalled £220m.

The regulator also fined JP Morgan £138m this year for the so-called London Whale scandal, for failing to control a single trader who wracked up huge losses on derivative plays.

But it's not just shady goings-on at banks that have contributed directly to the surge in fines.

The regulator has ploughed greater resources into a new enforcement division, where dedicated staff are more willing to unearth misconduct - as the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) itself says, "basically a tougher, more focused and resourced regulator."

Rule change

But where does all this money actually go?

All firms regulated by the FCA have to pay a membership fee to cover the regulator's costs. Prior to April 2012, the money collected by the FSA went towards reducing these fees, quite substantially so in some years.

In effect, then, financial institutions fined by the regulator benefited from lower membership fees, although given that the FCA regulates about 26,000 firms, the numbers involved are pretty small.

Since April 2012, however, the money collected from fines has gone straight to the Treasury. Last tax year, after "enforcement fees" of £40m, the government received £341m in fines from financial institutions - not a significant sum relative to the government's total receipts of about £600bn, but a not insignificant bonus none the less.

This tax year, the total will be higher still.

Help for Heroes

The Help for Heroes military charity has captured the public's imagination

The money goes into what is called the consolidated fund, which is effectively the government's current account for general expenditure.

But the Treasury has stated specifically that it intends to give money collected in Libor-related fines so far to military charities. In October, the government announced it would pay £35m to the armed forces community, external .

Among the recipients are Help for Heroes - which will receive £2.7m to support veterans suffering from mental health issues - the Royal Marines Families and Veterans Centre in Dorset, which is getting £2.3m, and Army Play, which was awarded £1.5m.

The government has also committed to transfer £10m a year from Libor fines "in perpetuity" to armed-forces charities.

And in the recent Autumn Statement, the chancellor announced that a further £100m of Libor-related funds would go not only to "our brilliant military charities" but "to extend support to those who care for the work of our police, fire and ambulance services".

However, the Treasury has given no indication of what the money will be spent on in future years.

It may well get swallowed up in general government expenditure but, for now at least, the money collected from bankers' dodgy practices is being put to good use.

- Published11 December 2013

- Published5 December 2013

- Published5 December 2013