US Federal Reserve turns 100

- Published

Simon Jack takes a look around the US Federal Reserve

On 23 December 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act creating the US central bank which this month celebrates its 100th birthday.

Created in the wake of the financial panics of the early 20th Century and in the teeth of deep suspicion of centralised power, it is now perhaps the most powerful financial institution on the planet.

The BBC was granted rare access to the Federal Reserve's inner sanctum - just a stone's throw from the White House.

It is here that a small group of unelected economists gather to take decisions which have profound implications for citizens in the US and beyond.

The financial crisis of 2008 probably did more than anything to make the Fed, its powers and its chairman, Ben Bernanke, familiar to people around the world, but it was just the latest episode in 100 years of crisis management.

Three tries

The early 20th Century was scarred by a succession of financial panics, the most acute of which followed the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco.

That prompted a group of leading politicians and financiers to meet in secret under the cover of a duck-hunting trip on the remote Jekyll Island in Georgia in 1910 to sketch out a central banking system.

This was actually the country's third attempt at a national central bank.

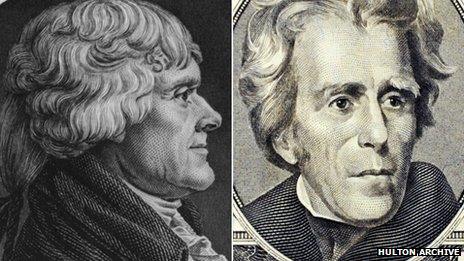

The first was created by Alexander Hamilton under George Washington in 1791, despite fierce opposition from Thomas Jefferson. It lasted only 20 years when its charter was allowed to expire.

The second attempt was put out of business by Andrew Jackson in 1836.

Former Presidents Thomas Jefferson (left) and Andrew Jackson both opposed a national, central bank

These first two efforts failed because of a distrust of centralised power that is deeply rooted in the American psyche, and the design of the Federal Reserve they eventually came up with reflects that.

At its heart sits the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) - made up of 12 regional bank presidents from around the country who reflect the agricultural, industrial and financial make-up of the US in 1913.

Added to those 12 are seven governors in Washington and together they form the committee which decides monetary policy. It can also intervene to provide emergency loans to financial institutions.

'Extreme stress'

These powers were used in dramatic ways during 2008 as the world financial system teetered on the verge of collapse.

Current chairman Ben Bernanke will leave the Fed in the new year

Richard Fisher, president of the Dallas Federal Reserve, says it was a nerve-racking time for everyone inside the Fed.

"For 18 months I don't recall having one night's sleep. Not one full night's sleep," he told the BBC.

"So, it was a period of extreme stress for all people involved and especially for Chairman Bernanke because this was the most complex, difficult environment in which to operate. Someone had to act and this is what central bankers do. We are the lenders of last resort."

The crisis in 2008 was by no means the first crisis the Fed has been through.

'Fluke of history'

The Great Depression of the 1930s was a test many historians and economists feel the Fed failed. It starved the US economy of credit when it should have been doing the opposite, they say.

Many people criticised the Fed's policy decisions during the Great Depression

According to Neil Irwin, author of The Alchemists - Inside the Secret World of Central Bankers, it was lucky the man in charge during the recent crisis, Ben Bernanke, had studied those lessons in detail.

"It was a unique fusion of the man and the moment that we happened to have this guy in charge of the central bank who knew what can go wrong when a central banker does not act decisively. It's really a fluke of history."

Perhaps the next big challenge after the Great Depression was the fight against inflation in the 1970s that saw the then-chairman Paul Volcker raise interest rates to 20% to remove money from the economy and kill off rising prices.

There were howls of protest from politicians and citizens alike. Construction firms dumped building materials outside the Fed in protest. Farmers circled the building with tractors.

But by the early 1980s - it had worked. Inflation had fallen to 3.2% by 1983, from 13.3% in 1979.

The next chapter

Janet Yellen is set to replace Ben Bernanke as chair - she will be the first woman to hold the role

One of the key strengths of the Fed system is its independence from politics. Having a chairman and board who are unelected, and span several political terms, shelters it from shifting political winds.

However, for some, this is also one of its main dangers. Some politicians, like former Republican Congressman Ron Paul, feel it has too much power and want it curbed or even abolished.

In February next year the mantle of responsibility is set to pass to the Bank's first chairwoman, Janet Yellen.

She will have to guide the Fed through the latest and possibly greatest economic experiment conducted in its 100-year history: quantitative easing - the injection of trillions of dollars into the US economy in an attempt to revive it.

At some point this has to stop and how the Fed manages this will be top of the new chairwoman's in-tray at the start of its next 100 years.

Inside the Fed will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 GMT, or listen again on iPlayer.