Chancellor’s return to 1948

- Published

- comments

There are a number of striking assertions by the Office of Budget Responsibility, whose forecasts underpinned the chancellor's Autumn Statement.

One is that by 2018-19, when the OBR expects the budget to be in surplus, as a result of a projected fall in the annual deficit by a remarkable 11.1% of GDP, government's "consumption of goods and services - a rough proxy for day-to-day spending on public services and administration - will shrink to its smallest share of national income at least since 1948, when comparable National Accounts data are first available".

This is pretty amazing. And it is because, on the OBR's analysis, around 80% of the reduction in public sector borrowing is "accounted for by lower public spending" - by what we have come to call austerity.

To be clear, these are predictions, not this moment's reality. And they would require a government after the 2015 election to stick to this administration's targets for taxing and spending, and translating those targets into budgets for individual ministerial departments.

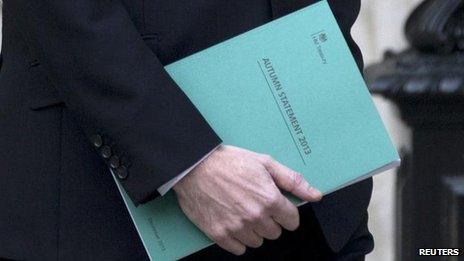

And the hypothetical nature of those longer-term targets are made clear in the Treasury's Autumn Statement book, because it does not - for example - make any provision for Nick Clegg's cherished, £755m-a-year policy of providing free school meals to the youngest school children beyond 2015-16.

But it shows that if George Osborne were to remain chancellor after the election, the austerity would roll on and there would be a significant reduction in what many would see as the state.

Now, for what it's worth, the OBR points out that on these forecasts, there will be a surplus on the "cyclically-adjusted current budget of 1.6% of GDP in 2018-19 which, it says, implies "significant headroom against the fiscal mandate".

Or to translate, the Tories could promise tax cuts in the run-up to the 2015 general election and still claim to be prudent (in its view of prudence) - as per my note of earlier today.

But what about the issue of more immediate concern to most of us, the strength and durability of the recovery?

Well on this, the OBR is cautious.

It points out that the first serious growth the UK has enjoyed since 2008 is being fuelled by what it calls "the unexpected strength of private consumption" which has "largely come from lower saving, not higher income".

In other words, households - whose finances in aggregate have still not been adequately mended, with household debt still high at around 140% of disposable income - are spending money they don't have.

Which means that if the recovery is going to be sustained for any length of time, business investment has to bounce back after the many long years of stagnation, and exports have to recover.

Strikingly, the OBR doesn't anticipate any marked improvement in net trade for at least five years. But it does forecast a significant 5% rise in business investment next year and sharp annual rises of almost 9% in the three succeeding years.

Goodness only knows how much of that will actually be delivered.

But it is necessary, if we're going to start feeling better off, after the bleak economic winter in whose thrall we've been since the Crash.

Here is the thing.

The OBR says that a "recovery in productivity growth is perhaps the most important judgement in our economy forecast".

Because unless the output of British workers improves, there will be no durable rise in wages or living standards. And all that belt tightening of recent years would have been for nought.

UPDATE 15:00 GMT

Here is something a bit odd.

Despite the economic recovery, the return to strong-ish growth - which the OBR did not expect in March - the OBR believes that the public finances have actually worsened a bit.

In the Budget, it expected a tiny 0.1% surplus in the cyclically adjusted current budget in 2016-17 (the Budget adjusted for the ups and downs of the economic cycle, excluding capital spending).

Today it downgraded that forecast, so there would still be a tiny 0.2% deficit in that version of the budget in 2016-17.

And there was a similar small downgrade to the 2017-18 forecast of deficit improvement.

Now these changes may be minor. But they are a bit counter-intuitive.

The OBR seems to be saying that, although this recovery seems to be strong, it is completely cyclical, a catch-up of some of the output lost in the last few years of stagnation.

Or to put it another way, the OBR implies the underlying growth rate remains worryingly low.

UPDATE 15:55 GMT

Where I think debate between economists will rage (as if you care) in relation to the OBR's forecasts and the Autumn Statement is over whether the OBR is being too pessimistic about the size of the so-called output gap and the UK's worsened prospects to improve productivity.

This is essentially a judgement about how long the current growth rate can be safely sustained, which in the OBR's view is not very long at all.

For what it is worth, the Bank of England is rather less pessimistic about this.

Which produces an odd contradiction.

Which is that the OBR presumably believes that growth at the current rate would fuel inflation, and force the Bank of England to put up interest rates.

But the Bank of England, which sets interest rates, apparently takes a different view.

So right now, the economic judgement on which the government is setting plans to tax and spend seems to be somewhat at odds with the judgement of the Bank when determining the price of money.

This contradiction feels weird.