Revolution brings no job hopes for Tunisia's women

- Published

Three years after the Arab uprisings, Tunisian women are struggling to find work, reports Simon Atkinson

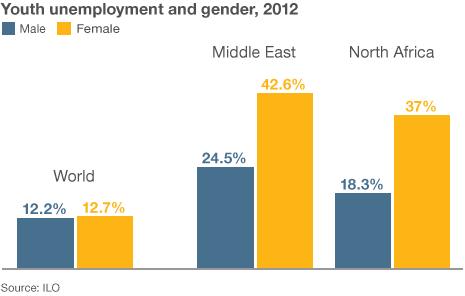

The revolution in Tunisia was partly fuelled by the massive levels of youth unemployment. Years later the situation isn't any better - especially for the country's women, who are at the back of the queue when it comes to most kinds of work.

By 10:30, the air in Le Mabillon cafe, just a couple of kilometres from the centre of the capital, Tunis, is already thick with cigarette smoke and chatter.

Most of its customers are in their 20s. And while some are students from nearby colleges - sipping dark, strong coffee as they tap at laptops - most have no class - or job - to go to.

For Asma Chalghoumi, the cafe has become a regular hangout since she was made redundant by a large advertising agency six months ago.

The 26-year-old is still finding it hard to adjust.

"The first thing I do when I open my eyes in the morning is check my emails - hoping to find an opportunity or a response to a job I've applied for," she says.

"I come to the cafe almost every day. There are lots of people like me who're unemployed. I chat to people, look online for work and then I go home. Sometimes I'll have a few days where I'm depressed - and I'll just spend the days sleeping, trying to get a bit more positive, then resume my search."

'Mentality'

The official unemployment rate in Tunisia is 16%, but among those under 30 years old it is almost double that - and far worse in some rural areas.

It is a problem showing no sign of improving since Tunisia's revolution, which marked the beginning of the so-called Arab Spring almost three years ago. Creating more jobs was a big demand of the protesters who ousted President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali.

In fact, if anything, unemployment has become worse.

Although reluctant to leave Tunisia, Asma's given herself a year to find a position before she contemplates following friends and moving abroad, perhaps to the the Gulf.

But statistically the odds are against her and that is not just because she is young, but also because she is a woman.

While 70% of men in Tunisia are classed as participating in the workforce, the figure is only 27% for women.

And according to many observers that long-standing gender imbalance is based on traditional ideas of women as wives and mothers.

"There's a mentality that unemployed men must have priority in getting the jobs, while the women need to stay at home to make way for these men to have work," says Radhia Jerbi, president of the National Union of Tunisian Women and a lawyer.

"Even if a woman is better qualified, it would be given to a man instead, unless it's in farming or textiles - jobs men won't do. But they're not getting the jobs that matter, in education, in management."

'Garbage'

The statistics suggest low levels of female participation in the workforce are not to do with education.

Young women make up about 60% of university students in Tunisia. Their grades are usually better too.

And with growth in the Tunisian economy tipped to slow to 3.2% this year from 3.6% in 2012, some argue that the lack of women in work is not just holding back their career prospects but also the development of the country, especially given their educational achievements.

"The country as a whole has put in resources," says economist Mahmoud Ben Romdhane, formerly a professor at the University of Tunis.

"We have a human capital that is not being used. This is garbage. This is not profitable. We are wasting resources."

And if all that university study feels like a waste of money for the country, it sometimes feels like a bigger waste for graduates such as Sahla Mseddi.

The 24-year-old finished university in 2011 - the year of the revolution -but has not found a job since.

She has done unpaid internships and, keen to be involved in Tunisia's civil society as the country rebuilds, volunteers with non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

But as she walks from business to business handing over her CV, she feels her prospects of work - especially in the area of TV and radio advertising that she studied - are proving increasingly dim.

"Employers want qualified people with a minimum of five, six, seven years of experience," says Ms Mseddi. "But I'm young. My limited experience isn't in high demand."

And while accepting that young men also have it tough, she argues that it can be even harder for women.

"There are jobs that are purely for men, which require physical exertion. But there are other things too. In my field you often have to work in the evening and that can be a problem to be a girl because our society is quite conservative. There's a thought that as a woman you shouldn't go home late."

Like so many of the young people in Tunisia, Ms Mseddi still has some hope - but that optimism for a significantly better life after the downfall of President Ben Ali has faded.

"My expectations for the revolution haven't been met," she says.

"It was us young people who said we wanted immediate change - that we didn't want to be unemployed. But the same problems still exist. It's depressing."