How Cirque du Soleil became a billion dollar business

- Published

Cirque du Soleil hires acrobats from more than 25 countries across the globe, 40% of whom are former athletes

At Cirque du Soleil's cavernous headquarters, located on the outskirts of Montreal near a landfill, unassuming office buildings do a good job of masking the, well, circus within.

But walk through the front door and the first piece of advice visitors are given is: "Don't try this at home."

It's hard to isolate just what one shouldn't attempt to do - jump from on the trampoline disguised as a bed, dive from a trapeze into a pit of foam cubes, transform a ballet slipper into a stiletto, or weave more than 150km (93 miles) of fabric into costumes capable of surviving water and fire.

At almost every turn, more than 2,000 of the firm's 5,000 global employees are engaged in the choreography, costume design, and acrobatics that have helped Cirque du Soleil become a global circus phenomenon.

With 19 touring and resident performances around the globe, in places like Las Vegas and Tokyo, the company takes in more than $1bn (£600m) annually.

Cirque du Soleil's Michael Jackson show features several hundred LED lights, some embedded in costumes

More than 150km of fabric are used to make costumes for the 1,300 performers in Cirque du Soleil's 19 shows

Choreographers use new techniques to surprise audiences - like this bed that doubles as a trampoline

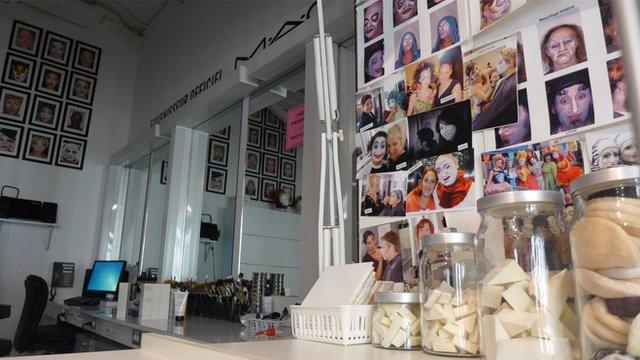

Cirque du Soleil acrobats are taught how to apply their own make-up, which can take hours each night

Wrestling shoes are favoured by acrobats, although there are several cobblers on hand to make bespoke shoes

But make no mistake: while the clowns might be driving the car, it's canny businessmen who are running the show.

"If you have a very good artistic product it's very well, but you have to have a good business management," says Gilles Ste-Croix, one of the company's co-founders and its current artistic director.

'Cherished kids of Canada'

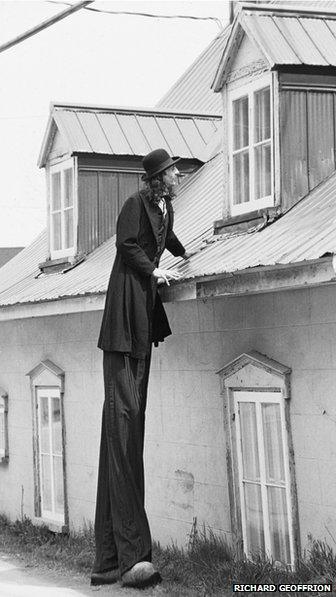

It all started in 1984, in the tiny Quebec City suburb of Baie-Saint-Paul, when a group of stilt-walkers and street performers formed a performance troupe called the Le Club des Talons Hauts (the High Heels Club).

Mr Ste-Croix walked 56 miles in stilts to raise money

After some local success, the group's founder, Guy Laliberte lobbied to have the group choreograph and perform at a celebration, called "Cirque du Soleil" (circus of the sun) marking the 450th anniversary of the European discovery of Canada by Jacques Cartier in 1534 - who claimed the land for France.

To raise money, Mr Laliberte convinced his partner, Mr Ste-Croix, to walk 56 miles in stilts.

"Every time I go up big hills I remember that night and I think, 'How crazy were you?'" says Mr Ste-Croix, who adds that perhaps his craziest thought was not thinking that this small troupe could end up this far.

After the success of that anniversary show, they decided to rechristen themselves Cirque du Soleil. The troupe quickly found fans eager to pay money to see its blend of acrobatics and art.

One crucial factor that helped it succeed was that Cirque du Soleil did away with the animals normally associated with circuses like Barnum and Bailey's or the Ringling Brothers. Instead, it focused on acrobatics in one big tent.

"Now the merging of acrobatics with the different form of arts is very common, but when we started, we were almost alone out there in our style," says Mr Ste-Croix.

Another crucial decision was to add permanent shows to the company's roster of touring productions.

In 1993, Mr Laliberte partnered with Las Vegas casino magnate Steve Wynn to create a permanent show called Mystere at Mr Wynn's Mirage Resort, and in 1998, the show La Nouba was inaugurated at Disneyworld in Orlando, Florida.

Finally, Canada's lack of a circus culture gave the company room to experiment and explore.

To help build the brand in Europe, the company first went on tour with Switzerland's Circus Knie and staged shows throughout the region. In 1995, it sought to further open the market with a five city tour of its show Saltimbanco under a big white tent.

The company also found success early on in Japan in 1992, which gave it a crucial entry into Asian markets.

Today, "we are the cherished kids of Canada," says Mr Ste-Croix, while noting that a majority of the company's revenues are generated outside the country.

Polishing the jewel

But with success has also come some hard lessons.

This year, the company suffered its first tragedy, when an acrobat in one of its Las Vegas shows fell to her death. It was later fined by US regulators for unsafe working conditions.

And, the company's two decade streak of never having a flop ended when chief executive officer Daniel Lamarre announced a plan to triple the company's output from one show a year to three in 2008. This led to what many felt was a decline in quality.

"The idea is to polish each show like a the jewel until it becomes a diamond and lasts forever - we lost some of that in that growth," admits Mr Ste-Croix.

For the first time ever, the company had to cancel shows and earlier this year, Cirque du Soleil announced it would lay off 400 workers.

"We like to think there has to be a 75% satisfaction and below that we don't think it's worth it," says Mr Ste-Croix.

"Of course we can hold on and make the return and the money and everything, but at the end of everything you know we only have our brand."

Cirque du Soleil had a recent hit with its show dedicated to the music of Michael Jackson in Las Vegas

Now, the company says it has renewed focus on its core offering - its performances.

It has found a hit in its Michael Jackson Immortal World Tour, which has helped soften some of the financial pressures.

And it has begun focusing on China, an increasingly important market.

"I've seen shows in different places in China and met the artistic director, who has seen all of our shows in Vegas and they are very proud to copy us. They say it's an homage that we pay to you," says Mr Ste-Croix.

"We have to penetrate that market in order to be the original product."

But above all else, he insists the company is still only as good as its last show, whether it's in Montreal or Beijing.

"We must not be too pretentious - we have to be humble," he says.