Ireland: Before and after bailout

- Published

After three years Ireland has left the EU sponsored bailout programme

Like cities across Europe in December, Dublin's streets are full of happy shoppers lugging their Christmas shopping home.

But three years ago, it was a very different scene. Noisy protesters had gathered outside Dublin's government buildings, demonstrating against the country's bailout.

In the midst of the eurozone debt crisis, Ireland was forced to accept a 67bn euros (£57bn) lifeline from the European authorities.

There was anger over the huge burden the bailout had put on Ireland's population.

Now, three years on, Ireland has left the bailout programme.

But few have forgotten the economic pain and particularly the bust in the property market.

During the boom, Dublin's skyline was a forest of construction cranes.

Low global interest rates allowed Irish banks to go on a lending spree, with much of the money ending up in the construction sector.

When the bubble burst in 2008, many companies could not pay off their loans and hundreds of property firms ended up going bust each month.

Jarlath O'Leary runs a crane hire business

Jarlath O'Leary experienced the boom and bust in the industry first hand.

His crane hire company did well during the good times, but when the crisis hit he saw demand drop by 85%.

He slashed staff numbers and reduced investment, but managed to survive while many of his competitors went bust.

Now the company is back in expansion mode and Mr O'Leary is positive about the future.

"It's different now from what it was like in the boom; business is much more like what it was historically," says Mr O'Leary.

Having fallen 50% from the peak, house prices are now up 10% in Dublin in the last year.

Residential construction is still fairly subdued but with Google, Facebook and Intel all expanding their operations in Ireland, there are hopes the building industry will grow in a more sustainable way.

"There are a number of big multinational companies that are investing heavily in new offices. Ireland feels like a good place to invest again," said Mr O'Leary.

Having had such a tough recession, many economic indicators in Ireland are bouncing back.

The economy has been creating jobs, with 58,000 new positions created over the last year.

The unemployment rate now stands at 12.5% (though this is still a lot higher than the UK's rate of 7.6%).

But the improvements have come at a price.

Public sector wages have fallen on average by around 20% since the start of the crisis and those in the private sector have also seen their pensions and pay slashed.

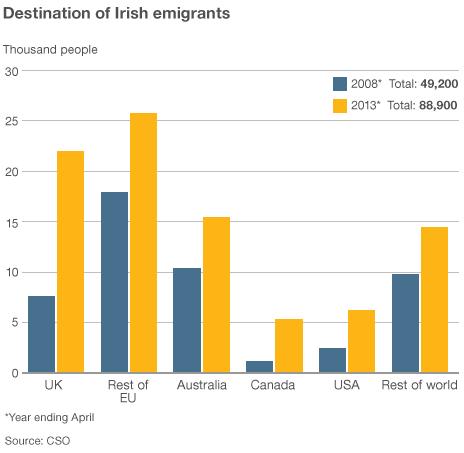

Part of the story behind the improved jobs numbers has been increase in migration from Ireland over the past few years.

In the last year, more than 34,000 young people have left the country, with the UK and Australia the two most popular destinations.

Crisis shadow

There's a feeling of relief and celebration around the main square of Trinity College Dublin.

The students filling out of exam rooms ready for the Christmas holidays seem positive about their futures, but the shadow of the financial crisis is never far away.

Cormac Noonan, 21, has seen the pressure of the lack of opportunities in the job market first hand.

His older brother was forced to move to Australia to find work in the construction sector and he is unsure if he will find work in Ireland once he finishes his degree in management and computing.

"It's tough for young people to have to move away to find work. It's also very difficult for their parents, with them being in places like Australia and Canada.

"But hopefully things will pick up and they can come back and work in Ireland again," he said.

The Irish government is trying to strike the right balance between trumpeting the country's achievements and warning about the challenges ahead.

It has already made 28bn euros worth of spending cuts and tax rises over the last three years.

"This is a very important moment. Three years ago this government was broke, we were in a position where nobody would lend to Ireland," says Eamon Gilmore, the deputy prime minister.

"Three years ago this country was losing 7,000 jobs a month. Now we are creating 5,000 jobs a month.

This is an "important moment" says Ireland's Deputy PM, Eamon Gilmore

"But there is still lots to do - we still have a very high level of unemployment, especially amongst young people," he said.

There are some who worry that a downturn in the world economy could have a serious impact on Ireland's heavily export-dependent economy.

But for the moment, many in Ireland are just coming to terms with what's become a rare commodity in past five years - good economic news.