The technology aiming to help refugees

- Published

Solar-panelled shelters are currently being tested at the UNHCR's camps in Ethiopia

Refugees and displaced people are, arguably, the world's most vulnerable people. They face the daily realities of living for years in shelters designed for emergency use while braving inhospitable environments, high temperatures, floods and little or no means of communication with the outside world.

While most users will spend an average of 12 years in refugee camps, current tent shelters have a lifespan of around only six months.

Now though, technology could help improve this. New prototype shelters, which are flat-packed and solar powered, are currently being tested by Somali families in camps in Dollo Ado, Ethiopia.

The panels have a guaranteed lifespan of three years, while the steel frame has a lifespan of 10 years.

The shelters are the result of a joint project between the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Ikea Foundation.

Empowerment

The UNHCR is leading the way in trying to find innovative solutions to some of the obstacles faced by the 45 million refugees and internally displaced people (IPDs) in the world.

It has created a division dedicated specifically to innovation and technology. Known simply as UNHCR Innovation, the division is headed by Olivier Delarue who enthusiastically describes his mandate as empowering refugees in new ways, including expanding opportunities to foster quality education and create genuine livelihood opportunities.

Just over 18 months old, UNHCR Innovation has quickly set about creating a number of key partnerships to support the creation of new processes and use technology to improve the lives of displaced people.

In addition to its collaboration with the Ikea Foundation, it has also teamed up with global courier service UPS to create a system to track the delivery of services and non-food items.

"We are tracking services through mobile devices so whenever we give something to a refugee and wherever we deliver a service to refugees, the system will know exactly what has taken place," explains Mr Delarue.

The solution, which is known as Liveconnect, is currently being tested in Ethiopia and will eventually allow UNHCR to track all non-food items that an individual receives from the organisation and its partners.

"This is about service quality: a dignified way to treat refugees as individuals rather than as labels or numbers. We are creating tools for these individuals to be empowered and not assisted," says Mr Delarue.

Reconnecting families

Being separated from friends and family is yet another hardship faced by many refugees.

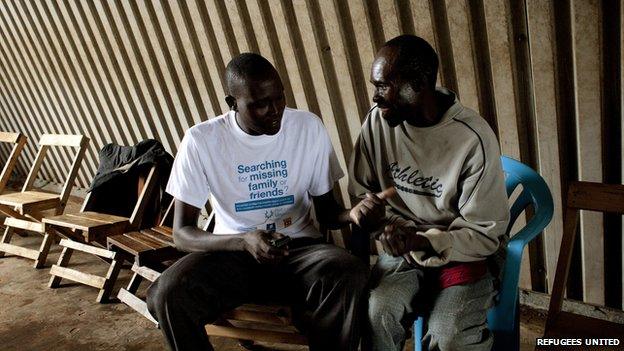

Danish brothers David and Christopher Mikkelsen set up family tracing platform Refugees United in 2008, inspired after meeting a young Afghan refugee trying to reconnect with his family.

In 2010 the system became available through a free mobile service, allowing people with even the most basic of handsets to quickly register their details via SMS, and be matched up with those looking for them.

Family tracing had previously been a laborious and intensive process done with pen and paper, with traditional non-profit organisations only able to help a small number of people.

"Our biggest partner in East Africa is the Kenyan Red Cross and up until we implemented our tools with them they would look at opening around 700 cases a year. Very often we open 700 cases a day at a relatively low cost," says David Mikkelsen.

Refugees United's platform can now also be accessed through unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) - a sort of souped-up text message system that works more like a secure form of chat - and via a toll-free number staffed by multi-lingual operators, as well as online.

It recently reached 250,000 registered users. Many of these are across Kenya, which has an estimated 500,000 displaced persons.

Working with communities

Both Olivier Delarue and Christopher Mikkelsen agree that it is vital not to simply impose a technology on users but instead acknowledge and refine the tools communities are already using to create solutions effectively across the digital divide.

"That is why we have on-the-ground partnership and why we have to build mobile teams around the technology. It is not about the technology in itself but instead about enabling people to become more efficient in the field by using technology," says Christopher Mikkelsen.

Both the UNHCR and Refugees United say helping people develop their existing tools is key

The South African-based Praekelt Foundation is dedicated to creating mobile technologies to assist non-profit organisations in working with society's marginalised people.

Praekelt has developed a mobile messaging platform called Vumi that aims to help organisations develop population-scale messaging applications.

"I think practically where this can affect refugees [in the future] is that we now have infrastructure where we can provide connectivity and access to information significantly faster than before," says Simon de Haan, Praekelt Foundation's chief engineer.

"One of the projects we are working on with Vumi is the text-based aspect of Wikipedia Zero, external. You can dial in with a USSD code and then you get a text-based menu on your phone to access information."

The idea is that people who only have access to feature phones can access Wikipedia articles. The hope is that in the future a dedicated Wikipedia page can be written to provide region-specific information to assist refugees.

But while technology clearly has a role to play in assisting and empowering refugees and displaced people, as Olivier Delarue puts it: "Importing new technologies is not a means in itself, rather it's mostly about working with communities to identify, amplify and modernise the solutions they are already developing."