Is Hollywood's blockbuster model broken?

- Published

"You're gonna need a bigger budget"

It may have lacked a generation-defining event movie like 1977's Star Wars, or even a technological groundbreaker like 2009's Avatar, but 2013 was still the year of the Hollywood blockbuster.

This year, 26 films costing more than $100m (£61m) each were released by the major Hollywood studios - more than ever before. They are likely to have raked in tens of billions of dollars in worldwide box office revenues as a result - close to the record $35bn (£21.5bn) delivered in 2012.

Some of the films did badly. The Lone Ranger, starring Johnny Depp, barely made back the $250m it cost to make. But the hits outweighed the flops: Iron Man 3 took $1.2bn in box office receipts around the world, topping the charts and making it the fifth highest-grossing film of all time.

But despite the runaway successes, there are concerns within Tinseltown that blockbuster budgets are getting dangerously high.

Bankrupted

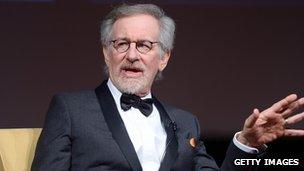

"There's eventually going to be an implosion, or a big meltdown," said Hollywood elder statesman Steven Spielberg in a speech earlier this year. "Three or four or maybe even a half dozen mega-budget movies are going to go crashing into the ground, and that's going to change the paradigm."

Steven Spielberg has warned of an "implosion" in Hollywood

It has happened before. In 1980, Heaven's Gate effectively bankrupted United Artists. The budget for the sprawling Western got out of control, the film bombed, and the studio was forced into a takeover by MGM.

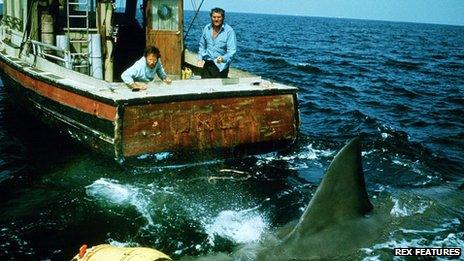

The irony is that Spielberg almost singlehandedly invented the blockbuster genre. When his film Jaws was released in 1975, Hollywood realised that making a few big-budget films a year that appealed to the masses was more lucrative than making dozens of smaller ones, and a business model was born. Since then budgets have soared and artistic merit has taken a back seat.

Hollywood watchers say it's a statistical certainty that another bomb to rival Heaven's Gate, or even 1995's Waterworld, is around the corner. But the difference, they say, is that modern Hollywood studios are equipped to cope.

After a wave of acquisitions in the 80s and 90s, the six "majors" that dominate global box office are now parts of massive media conglomerates. They have found ways to both boost profitability of their films and mitigate the risks associated with making such huge investments.

The first thing the studios have done is spread the risk by getting dozens of smaller production companies to invest alongside them, reducing their exposure to a potential flop.

Revenue streams

The second thing is that they have made the success of their films almost a sure thing.

Recent research by British film academics John Sedgwick and Mike Pokorny has found that not only have blockbuster films become more profitable over the past 20 years, they have become more reliably profitable: in the late 80s just 50% of major studio films turned a profit. In 2009 it was 90%. Flops have become rare.

"[Studios] are ruthlessly good at getting returns from their investments," Prof Sedgwick says. "Hollywood has got better and better at it. The more you spend, the more you get back. It seems to me to be an extraordinarily successful model."

How have the studios achieved this?

The first step has been to generate new revenue streams. In the early days of Hollywood, 100% of revenues came from ticket sales. Now it's just 20%. The rest of the money comes from television licensing, DVD sales, merchandising and other commercial deals.

"Blockbuster films are not really films," says Charles Acland, a professor of communication studies at Concordia University in Montreal, and author of the book Screen Traffic. "They are in fact very elaborate 'tent-pole' business models that connect all sorts of different commodities in all sorts of different industries."

The second step has been to look beyond the domestic US market, where cinema audiences aren't really growing, and look overseas to developing markets such as China.

Iron Man 3's marketing this year focused heavily on newer markets like China

Iron Man 3 earned two-thirds of its revenues outside of the US. The Chinese version of the film even had four extra minutes of footage, featuring Chinese actors and half a dozen Chinese product placements.

Finally, the studios have become incredibly risk-averse in terms of the types of films they produce. Instead of taking a chance on new directors and original ideas, they produce tried-and-tested franchises, remakes and book adaptations.

Communal experience

A look at this year's top 10 highest-grossing films reveals just two original screenplays - animation The Croods and 3D epic Gravity. In both 2012 and 2011 there were none in the top 10.

As a mark of the power of the franchise, The Amazing Spider-Man was released last year, and Sony has already pencilled in dates for The Amazing Spider-Man 2, 3 and 4 stretching until May 2018.

That's on top of Spider-Man 1, 2 and 3 released between 2002 and 2007.

Hollywood faces challenges. Executives are sweating over a virtual collapse in DVD sales in recent years amid the growth of online streaming services such as Netflix. The major conglomerates that control the studios are seeing profits faster at their television arms than in the film industry, and are cutting costs.

But perhaps the more worrying long-term problem is what Charles Acland calls "aesthetic bankruptcy". The blockbuster business model necessarily leads to making bad movies.

The perception that Hollywood peddles lowest common denominator crowd-pleasers at the expense of "serious" cinema means screenwriting talent is increasingly moving over to television. This year director Steven Soderbergh threatened to quit altogether.

But while blockbuster franchises continue to bring in billions worldwide, there is little sign that Hollywood will change its ways.

"If you want a shared communal experience of the film that everybody's talking about right now, then you go to the movie theatre," Prof Acland says. "The blockbuster is very stable in Hollywood. It's not going to go away any time soon."

- Published9 December 2013

- Published3 September 2013

- Published7 August 2013