Australian tennis looks to bounce back

- Published

As Phil Mercer reports, the road to the top is immensely challenging

Tennis is part of the essential soundtrack to an Australian summer: balls rocketing off strings, the squeal of overworked footwear on baking courts and the grunts of heavy exertion.

It's a sport that Australia once dominated. In the 1960s and '70s the nation built a triumphant global legacy - Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Roy Emerson and John Newcombe were imperious, while Margaret Court and Evonne Goolagong Cawley became sporting royalty.

But since the early 1980s, Australia's women have claimed just a solitary Grand Slam singles title, and it's more than a decade since the evergreen Lleyton Hewitt became the last Aussie man to win a major, at Wimbledon in 2002.

Changing times?

The trophy drought has caused despair among the country's tennis aristocracy.

The Open in Melbourne brings healthy revenues to Tennis Autralia

"We just wondered where the next group of top players was coming from," says Rosewall, who won eight Grand Slam singles titles.

"I think we've just been unlucky that we haven't had a nucleus of top players that were ready to go along with Lleyton (Hewitt).

"Over that period of time Australian people were disappointed we were not doing better, but let's hope that has changed."

Bankrolled by the riches generated by the sale of TV rights at the Australian Open, Tennis Australia, the governing body, has been pouring money into community projects, hoping to unearth new gems.

Championship windfall

"Tennis Australia puts the broadcast revenue into the grass roots, and I think that is why tennis is picking up in Australia like never before," explains Tim Harcourt, an economist at the University of New South Wales.

"There was a bit of a crisis in 2006 where there wasn't much Australian talent at the top and people were pulling out of tennis," he says.

"Tennis Australia decided to basically restructure the whole sport and put more money into the community - [money] that they were getting from [Roger] Federer and Serena Williams here... using those revenues more wisely."

The Australian Open provides a windfall not just for tennis.

It pumps around 238m Australian dollars (£130m; $214m) into the Victorian state economy.

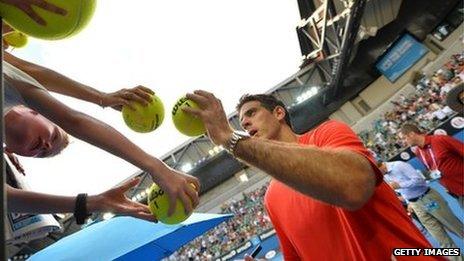

Tennis has remained popular with Australian spectators

It attracts 800,000 spectators and visitors to Melbourne, while global television audiences top 300 million.

Tennis is one of the most popular sports on Australian TV but a local last won the first "slam" of the year in the 1970s. An impatient nation waits for a fresh generation of stars.

'Hard work'

At the Jaggard-Ibarrola Tennis Academy in Sydney's leafy northern suburbs, pint-sized warriors do battle in a junior competition.

Coaches say there can be a challenge making youngsters stick with tennis

The future of Australian tennis is in these eager, young hands, and from these hard-hitters there could emerge the champion that this sport-mad country is so desperate for.

But tennis, like other sports, often has problems keeping new recruits.

"Sometimes life for some youngsters can be a bit easy and they probably choose other ways, and in the past we had more people willing to do the hard work," said Fernando Ibarrola, a former Argentine professional, and coach at the centre.

A child's passion can be expensive and time-consuming for parents, and making it to the top is unquestionably tough, requiring precocious talent, and sacrifice.

"You've got to have a package, and that's the hardest thing to be a really good player. You can't just have a good technique, you've got to be physically very good, you've got to be mentally very sound and tactically understand well," explained Michelle Jaggard, an ex-Australian Federation Cup player.

"On the court they really have to put their child mind off the court and become a bit more adult thinking, and it is not an easy thing to do because they want to be kids."

'Train and train'

Shanté Lai hits the ball as deftly as any 10-year-old in the competition.

She trains for 10 hours a week with professional coaches, and along with doubles partner Chelsea Pernice, lists the verve and grit of Serena Williams as her guiding principles, although the girls admit that their schedules are taxing.

Sam Stosur's US Open win in 2011 has given hope to young Australian players

"I miss sometimes my friends because I have tournaments and training," says Shanté.

"But if you really want to be up in the top 10 and you are really passionate about it, you do anything to be up there to be playing tennis for your life," adds Chelsea, 12.

"I just think that to myself when I miss out on a birthday party or a sleepover, it doesn't matter - you can have plenty of them in your life after your tennis career. Just train and train."

'Really tough'

Success at the very top does filter down to the grass roots, and serves to encourage those who are willing to put in the serious work.

Sam Stosur's triumph at the US Open in 2011 did lift Australian spirits, but as the global business of tennis becomes more lucrative and the competition intensifies, the nation's past domination of world tennis seems unlikely to be repeated.

"When I was coming along in the late '80s, early '90s, there were about 1,000 players ranked on tour," said Todd Woodbridge, an ex-Grand Slam doubles champion and former head of professional development at Tennis Australia.

"Now there are 2,000. So, when we look at those glory days and that of Australian tennis, we have to be realistic and say we were a really big fish in a small pond back then and now we are just one of the numbers that make up this sport.

"To be honest there is no way we are going to get back to where we were. We might get one player but it is going to be really tough to get the numbers we once had."

Success, of course, is measured in many ways.

For Australian tennis, it's not just about glory at the elite level but also the social and health dividends of encouraging more people, especially children, to pick up a racquet and to savour the sound of a sweetly struck forehand.