Smashing the tennis money barrier

- Published

Jonathan Legard meets aspiring tennis pros living on a tight budget

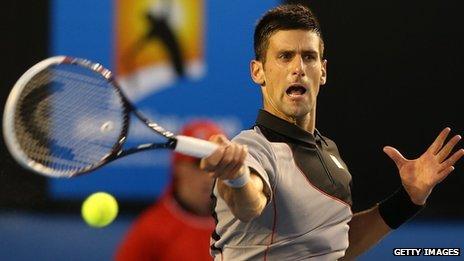

The four-time Australian Open champion Novak Djokovic may have gone out of this year's tournament, but he remains an inspiration to one of Britain's up-and-coming young players.

Scott Clayton, UK under-18 champion in 2012, was a practice partner for the world number two at the World Tour Finals, which the Serb won, in London last November.

The teenager's ambition is to achieve similar greatness but a racquet and tennis balls are currently all that the two players have in common, however.

Djokovic has earned more than £23m ($38m) in prize money in just three years. Last month he hired the former Wimbledon champion Boris Becker as his coach.

Clayton, by contrast, is struggling to make ends meet on the Futures circuit, the third tier of the men's professional game, despite continued financial support from his parents.

"I'm not breaking even at all," the 19-year-old says.

Scott Clayton is one of the most promising young players in the UK

"You go to tournaments trying to get ranking points and win money but it's tough," he says in the MCTA/Team Bath tennis academy, situated at the city's university, where he trains full-time.

"You're getting a lot out of it on the court. But money-wise, no, not really."

Clayton's coach is 27-year-old Jamie Feaver, for whom tennis runs in the family.

His father John represented Great Britain in the Davis Cup and once held the record for the number of aces served in a single Wimbledon match.

Feaver Jr spent seven years as a tour professional before moving into coaching, and knows first-hand the challenges facing Clayton.

Being talented at tennis is only half the battle at this stage of a fledgling career, he says.

"When we're here with all the facilities, it's fine. When you're on the road, it's a case of survival.

"You've always got your mind on expenses. You've always got to keep them as low as possible."

"You make all the arrangements yourself. You stay in the cheapest hotel possible. You're eating the cheapest food, wondering, 'can I get another drink?'"

Jamie Feaver spent seven years on the tennis tour before becoming a coach

In a typical year, Feaver's expenses as a player were £15,000 ($25,000). His income was regularly a fraction of that, despite his best efforts to cut costs, even if it meant more travelling.

"I once went from Bucharest in Romania to a tournament in north-west Bosnia. I took two-day train rides instead of a $200 (£120) air fare.

"I won my first-round match; then I lost and had to get back to where I started."

He adds: "After a trip like that, one match was the maximum I was going to win. Then you get drained emotionally and physically."

Feaver was able to cover his costs each year thanks to his success in lucrative club matches in Europe and because of a financial backer.

But it left very little for anything other than tennis and inevitably schedules took their toll.

"It's always at the back of your mind how much money you're spending.

"You know around the corner you're always going to have to struggle," he says.

'Tighter funding'

With cost-saving firmly in mind, Clayton lodges with Feaver in Bath, with the pair scouring travel websites chasing the best deals.

"You know you're saving money and doing the right thing, but maybe not the best thing," says Clayton.

Scott Clayton spends hours looking for cheap travel deals

Their struggles form a familiar tale in the quest for a professional career.

Team Bath's director of tennis, Barry Scollo, was himself in the top 100 on the Junior ITF circuit during his time on tour.

He and his coaches understand they are preparing their players at a time of intense competition globally.

"It's always been tough but it's certainly getting tougher," he says. "There are more players [and] more countries involved in tennis.

"The funding is getting tighter and we've got to make more of the resources we have.

"It's important that we paint a picture of the Tour: the physical demands, the mental demands."

These become even greater during periods of injury and illness.

No tournaments means no earnings and potentially missing out on qualifying for a Grand Slam; at Wimbledon in 2013, first-round losers received £23,500 ($39,000), considerably more than Feaver's annual expenses on the Tour.

And as well as their usual living expenses, players face additional bills for scans and physiotherapy, plus the cost of repairing or replacing equipment.

For top players such as Djokovic, Andy Murray, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer - who have equipment deals and multi-million pound sponsorships - those issues will be taken care of by others.

'Every point counts'

Scollo acknowledges that financial support can affect performance, but says personality is a key factor too.

Scott Clayton practised with Novak Djokovic, and now wants to face him for real

"Money on its own never made a player. It certainly helps but it always comes down to the individual."

Clayton enjoyed his best season in 2012 when he earned a wildcard entry to Junior Wimbledon's singles and doubles.

That early success helped focus a desire that saw him leaving home aged 11 to become a professional player.

His first year on the Futures circuit was challenging, but now he knows what to expect and believes can cope when "every point and every match counts".

And having practised against Djokovic, Clayton is even more determined to face him for real.