The financial implications of young and old returning home

- Published

Kevin Peachey reports

Laughing and joking as they flick through the latest make-up offers, Janice Parker and her daughters Jerri and Isobel look like a typical family spending a fun evening together.

Jerri is 33 and Isobel is 21, but this is not an occasional family reunion.

Along with their 28-year-old brother David, Jerri and Isobel still live with their mum at the family home in Darwen, Lancashire.

They pay board, but like a growing number of young adults in the UK, they feel as though they cannot afford to buy or rent separately.

"I get paid well, particularly for this area," says Jerri, who works for a defence company.

"But looking at trying to get a mortgage, I just couldn't afford it. By the time you add in all the bills, I just couldn't survive."

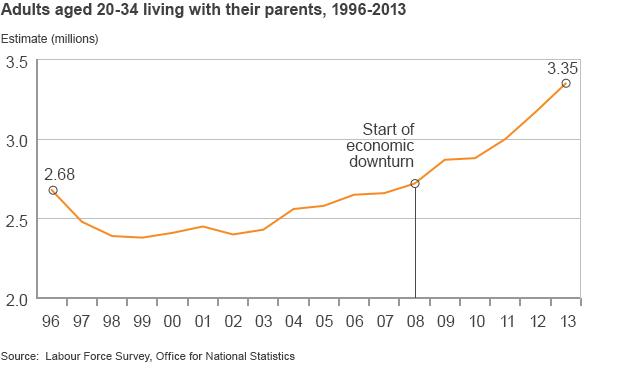

More than 3.3 million adults between the ages of 20 and 34 were living with parents in 2013, 26% of that age group, according to the Office for National Statistics, external.

They are known as the boomerang generation, as they often return to live at home after a spell away or at university.

The number has increased by a quarter, or 669,000 people, since 1996. This is despite the fact that the number of 20 to 34-year-olds in the UK remains almost the same, the ONS says.

Some 72% of these young adults - like Jerri - are in work, not far short of the proportion of working young adults who live in shared properties or homes of their own.

But for those looking to fly the nest, even by the time they have entered their 30s, the burden of housing costs is the overwhelming factor to consider.

The ONS said that, in 2013, first-time buyers in this age group were facing typical house prices that were nearly four-and-a-half times their annual income. That compares with house prices of 2.7 times annual income in 1996.

While the latest figures show that the cost of renting a home has risen by lower than the rising cost of living in general, at 1% annually, there is a chance that the cost of being a tenant could continue to go up.

Unpaid carers

This is an not issue that only affects the younger generations.

Steve McIntosh says that there is a range of financial implications to consider

Many older people who find they need care in their later years will move back in with their children.

Relatives may consider it their duty to provide unpaid care for elderly members of the family. The 2011 Census found that one in 10 people devote at least part of their week to caring for disabled, sick and elderly relatives or loved ones without expectation of payment.

Carers UK, which represents unpaid carers, estimates that 715,000 people live with and care for a parent or parent-in-law.

Policy manager Steve McIntosh says this can create some financial hardship for everyone involved.

"Caring is a normal part of life. But many people do not realise it brings huge financial costs, as well as the emotional and personal pressures of caring," he says.

"So while families think it is their duty and responsibility, often they do not realise that it could involve sacrificing their careers and ending up in real financial hardship."

Planning a budget

Many families do have some warning that a relative - young or old - is going to be living with them again.

The Money Advice Service suggests that it is extremely important to sit down as a family and talk through the implications as a family.

Jackie Spencer, from the service, says that families need to consider all the incomings and outgoings.

That includes checking that they are claiming all the benefits to which they are entitled, but also budgeting for the extra food and energy bills that will naturally result.

"Communication, especially around money, is the key," she says.

"People find it easy if they actually approach the subject. Where it becomes difficult is when you don't talk about it, and then things start to erupt when you don't address the issue."

The Money Advice Service has an interactive budget planner, external that can help families go through their finances and might remind families of any benefits that they can claim.

While the addition of an extra body in the family home can bring financial strains, Janice Parker, who works for a credit union, says she is helped by the continued presence of her grown-up children at home.

Their contributions help pay the bills, but there is also a personal thrill to having them all still at home.

"There are enormous benefits for me," she says.

"I get to share their lives with them, and I've got to know them all as adults. We have the sort of conversations that good friends do."

After all, many families will think that spending time with their loved ones is so much more valuable than the concerns of spending money.

- Published19 December 2013

- Published11 February 2013

- Published21 January 2014

- Published21 January 2014

- Published21 January 2014