The meaning of Labour's tax rise

- Published

- comments

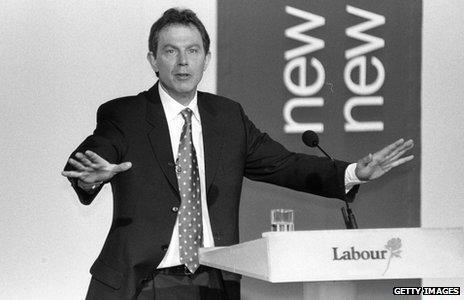

People often moan that politics and politicians never change, but there has been a big shift in the attitude of the Labour Party in its attitude to big businesses and high earners, from the period when Tony Blair led the Labour party in opposition in the mid-1990s to today's opposition Labour Party.

When Blair was in charge, I was the FT's political editor. Therefore, I took a particularly close interest in Blair's relations with the big-cheese bosses and plutocrats.

His calculation was that Labour could not win if it was seen to be opposed to what he defined as aspiration and wealth creation. So most of his waking minutes were devoted to wooing business, especially big business, and creating the impression that a Labour government would raise neither the top rate nor basic rate of income tax.

The epitome of this policy was his burning ambition - which was only ever half fulfilled - to secure the endorsement of Richard Branson (before the election, the great brander created the impression he was on New Labour's side without actually saying anything explicit).

New Labour's determination to impose a windfall tax on the privatised utilities might have looked in some way anti-business. But in practice the remuneration and pricing policies of these companies had so alienated most "proper" private-sector business folk that they just about gave the party the benefit of the doubt.

And, by the way, it is reasonable to conclude today that this was conviction politics on the part of Blair, given the colossal amount of money he has made from advising big businesses and multinationals since stepping down as Labour's leader.

All of which does seem a world away from today's Labour party under Ed Miliband.

He would and does say that he wants to support the growth and proliferation of smaller businesses.

But his plans to impose a price freeze on energy companies, to break up the biggest banks and to raise the top rate of tax from 45p to 50p is angering the boss class, to the extent that quite a few are breaking the habits of a lifetime and making critical public statements.

So what's changed between 1996 and 2014? Well to state perhaps the most obvious and least interesting distinction, in the spectrum of views that constitute the Labour Party, Miliband appears to be slightly to the left of Blair.

But so much else has changed of an arguably more fundamental sort.

In an economic sense, the UK was four years into a strong recovery in 1996 and living standards were rising sharply - which may have helped to curb popular resentment, to an extent, of higher earners.

And in the zone of ideology, Thatcherism was still massively in the ascendant - Margaret Thatcher had shifted the middle ground of politics and converted Blair and the top of New Labour to the idea that economic growth and prosperity were best secured by the unleashing of market forces.

How different from today. We are in the early months of a recovery and living standards for most people have been squeezed for many years and are not yet improving.

Also the banking crisis of 2008, which triggered the long dark years of recession and economic stagnation, has made respectable again the idea that the private sector cannot always be trusted to deliver optimal economic outcomes for all of us (ahem).

Then there are two other things.

Newspapers, which have a tendency to be hostile to tax rises and intervening in markets, had much bigger circulations in the 1990s than today. And Labour now has the ability through social media to go round them.

But perhaps for me what is most striking is that Labour seems to have calculated that it can win the election by hanging on to the support of LibDem refuseniks, or those marginally to the left of the centre who voted LibDem last time but have been alienated by its participation in the coalition.

He does not seem interested in eroding the Tories' residual support.

Or to put it another way, Miliband seems to believe he can win the election by standing largely on the left, which is so different from Blair's strategy (and tactics).

Which means that the dividing lines between the two bigger parties do feel much more as they did in the 1970s, rather than in the 1990s.

What about the actual costs or benefits of raising the top rate of tax, to the Exchequer and the economy?

Well if I haven't dwelled on these, it is because the evidence is murky.

After Labour introduced the 50p tax rate just before the last election, there was a huge amount of what is known as income shifting and income converting: bonuses, for example, were brought forward and paid before the new tax bit; income was converted into capital, so that it could avoid income tax; and various other devices were employed to dodge the higher rate, sometimes permanently, sometimes temporarily.

As for whether it drove wealth creators from the UK, there the facts are even harder to find - a few hedge fund superstars have moved to Switzerland (which not everyone weeps about), and lots of French capitalists have moved to London, to escape President Hollande's even higher taxes.

There might be a good deal of income shifting and converting again, if the rate went from 45p to 50p, which would reduce the take from the imposition of the higher rate.

But the amounts of money gained or lost from the tax rise, as the Institute for Fiscal Studies has said, may be pretty trivial, probably less than a percentage point of the annual hole or deficit in the government's finances.

Which is why what is more interesting about the planned tax rise is what it says about battle lines in politics, and the parties' attitudes to high earners and businesses.