Start-ups challenge big banks' technology

- Published

The small guys are taking the challenge to the big banks

Big banks beware - innovative technology challengers are coming to eat your lunch.

That was the key message emerging last week from FinTech City London, external, a series of events for financial services technology professionals organised by the CEO Agenda and Icon Corporate Finance.

Fintech, as financial services technology is modishly called, is enabling nimbler, hi-tech companies to re-engineer most financial activities, from payments processing to personal loan applications, and cut out the middleman.

It's what Clayton Christensen, professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, calls "disruptive innovation", external.

While the things we do with money - save, borrow, invest, spend - have not changed much over the centuries, the way we interact with financial institutions is "drastically changing", said Alex Scandurra, director of innovation strategy and business development at Barclays.

'The micro multinational'

And that's largely to do with mobile, open-source databases and cloud computing. About three-quarters of the UK population owns a smartphone, and there are more than five billion mobile phones globally.

Funding Circle provides a direct link between investors and small firms

"As a result of the proliferation of technology, digital, and now mobile with it, the barriers to entry have significantly decreased," said Mr Scandurra. "Now we're seeing that teams of 10 to 15 people can actually take on the large incumbents all around the world."

Whereas big financial institutions have to cater for a mass market and try to please everybody, small fintech companies can focus on niche markets, globally spread. They can form what futurist and writer Alvin Toffler called "the micro multinational".

One such company is Funding Circle, the peer-to-peer (P2P) lending service launched in 2010, which aims to provide businesses with access to loan funding while providing investors with a decent return on their money. Its 65,000-plus investors have lent over £208m to UK businesses so far.

In March 2013, the UK government began lending £20m to British businesses through Funding Circle as part of its Business Finance Partnership scheme, external.

Co-founder and chief executive Samir Desai said that while his company had certainly benefited from the 2008-13 banking crisis and the consequent collapse of trust in High Street banks, it is new open-source technologies and databases that have enabled P2P lending companies to grow.

"Every loan that goes through Funding Circle is funded on average by 700 different people," he said "Those loans can then be bought and sold by other investors through a secondary market. So we have as many mini-loans going through our system as any bank, and thousands of secondary market transactions going through each day.

"We couldn't have done that without these new open-source technologies."

New credit scoring system?

Open-source databases that anyone can access and adapt, such as Hadoop and Cassandra, can process and structure vast amounts of data from a wide and growing range of sources, including social media, helping P2P lenders and other financial companies assess creditworthiness to much higher degrees of accuracy than before.

Mobile payment companies like Square offer new technology to merchants

"Banks haven't started to embrace these new types of technology," said Mr Desai. "So we can lend to businesses they wouldn't even consider."

So now even your Twitter comments could affect whether or not you're granted a loan, and companies like Facebook could end up displacing old-fashioned credit reference agencies.

Giles Andrews, chief executive and co-founder of Zopa, a more established P2P lender founded in 2005 that has lent more than £455m to individuals and sole traders, agrees that customer data - its efficient collection and analysis - is key to success these days.

"The business is not a bank and I'm not a banker," he added. "We're more of a data company."

This is why Zopa has just hired its first ever chief data scientist, he said, who comes not from a bank, but from Amazon, the online retailer.

Legacy issue

Newer fintech companies are not encumbered by old technology, the so-called legacy systems that traditional banks struggle to integrate with newer software and hardware.

The Lloyds Banking Group IT glitch, which affected debit card and cash machine transactions at the weekend, is the latest in a long line of big bank technology problems.

"It's an opportunity for the new challengers who don't have that legacy issue," said Sue Langley, chief executive of UK Trade & Investment's Financial Services Organisation, "because it's much easier with a blank sheet of paper to.... come up with something new."

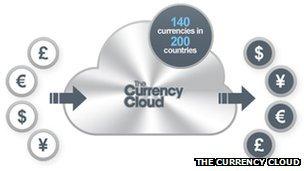

The Currency Cloud provides technology to international payments companies

"The banks have an increasing need for technology," said Mark Boleat, chair of the City of London's policy and resources committee. "Some of that comes from their huge IT departments, but an awful lot of it is coming from new and start-up businesses."

Alex McCracken, director of ventures groups at Silicon Valley Bank's UK arm, believes we will see a polarisation in financial services, with global all-you-can-eat banks serving multinationals at one end, and small, technology-driven niche players serving local needs at the other.

"Corporates and small businesses are going to be able to pick and choose their niche service providers," he said.

The mouse that roared

Mobile payment companies like Square, simpler direct debit providers like GoCardless, and foreign currency specialists like The Currency Cloud, all are offering financial services at lower cost and greater convenience through clever use of the latest technologies.

Are the big banks running scared?

Last week, US banking giant Wells Fargo banned some of its staff from investing in for-profit P2P lending companies, external, such as Lending Club and Prosper, admitting that they were competitors.

That is the wrong approach, argues Barclays' Alex Scandurra. His bank is collaborating more with tech entrepreneurs and start-ups, as well as offering non-banking products such as Cloud It, an online data storage service.

He calls the approach "amplification through collaboration".

Labour leader Ed Miliband may want to increase competition by forcing big UK banks to offload High Street branches, but to many observers, this is a red herring.

It is technology that is helping the fintech mouse take on the giants and roar.