Charity helps deaf Indians get into the workforce

- Published

Haider Ali points to options on the menu to communicate with customers

It is the afternoon at the DLF Place shopping centre in Delhi. Well-dressed Indians cruise its lofty atrium, sipping lattes, trying on designer sunglasses or the latest Indian couture.

It is the last place you would expect to find Haider Ali.

Mr Ali, 32, has been deaf since birth. His childhood and adolescence were spent trapped in a mute world where no-one taught or spoke sign language.

There are 1.2 million deaf Indians, according to census figures. Yet India has few specialised schools for them.

Hearing teachers sometimes even force deaf children to parrot speech. As disability is seen in India as a curse for sins committed in a past life, it is no surprise that the country invests little in disabled facilities.

"In my school, the teachers treated us very badly. It used to make me angry," Mr Ali says through a sign language interpreter.

"They would just write on the board but they could not explain what they were writing. It was very difficult to learn."

Most deaf Indian children reach adulthood with a vocabulary of just 50-odd words, and little ability to understand or cope with the world. They are rarely employable.

But at Joost, a juice bar offering more than 30 mixes, Mr Ali takes orders with a ready smile.

"Hi, can I order something?" says a middle-aged man before noticing Mr Ali's sign language. "Oh, I'm sorry."

Mr Ali quickly gives the man a menu and points to the options, using his hands to indicate small, medium or large before scooping up fresh fruit and ice cubes into an industrial blender and ringing up the order.

'It's high-energy'

After an 18-month course, students are helped to find work

He and hundreds of other deaf people found jobs through the Noida Deaf Society (NDS), a charity that runs a primary school and five employment training centres around the Indian capital.

At its headquarters in a Delhi suburb, there is almost complete silence, even though several English and computer classes are in full swing.

All the instructors are hearing-impaired, and sign language is used along with flat-screen TVs and visual aids to conduct lessons.

"Students are not to use mobile phones in class," reads a sign on the walls.

"It's not a joke," says Ruma Roka, the charity's founder.

"Most of these kids have phones and they're communicating with each other through texting, WhatsApp, Facebook or video chat.

"With one hand they're holding the phone and the other hand they're signing, talking to friends across the country.

"The teacher often complains to me that the minute he turns to the blackboard, they're chattering away - who's wearing what, who likes who. It's high-energy here."

Charity founder Ruma Roka (right) with deaf students, whom traditionally India has done little to help

'A business case'

NDS turns no-one away and charges students no fees, relying instead on private sponsorship.

Many students come from impoverished families, but even middle-class children find help is not available elsewhere in India.

After 18 months' intensive sign language, written English and computer skills, students receive assistance in finding jobs.

But Ms Roka insists hers is not a charitable model.

There are areas in the IT industry, banks and retail, she says, that suffer from a high attrition rate, or staff turnover, she says: "Up to 60% in some companies, so we made a business case.

"We said, you employ some of our deaf kids and the company will make indirect money - because the attrition rate drops from 60% down to 5%."

So far, Ms Roka has placed 828 students in companies as diverse as animation studios, hotels, coffee bars and banks.

"They're not working as menial labour. They're working in formal industry," she says.

Morale boost

Can disability even be an asset?

FIS Global Business Solutions, based in Gurgaon, a key Indian finance and industrial centre near Delhi, hired two full-time deaf employees last year.

Alok Sagar (left) and Vipin Kumar, both deaf, are the first hearing-impaired workers at FIS Global Business Solutions in Gurgaon, a key Indian finance and industrial centre near Delhi

The company, which processes sensitive financial data for US banks, believes the ability to filter out distractions leads to greater accuracy.

"This is high-end work," says Manpreet Singh, head of employee relations at the Indian headquarters of FIS.

"They are looking at scanned images of personal cheques. Any transaction that goes wrong would mean money getting debited from the wrong account and affects our service levels."

Mr Singh is also convinced that, long-term, hiring disabled employees is a good bet.

"When I look at it from an HR perspective - the attrition rates - these people are hardworking. So it's a win-win situation."

The International Labour Organization (ILO) says there are a billion disabled people around the world, about 15% of the global population.

They are more likely to be unemployed, even though hiring disabled workers has tangible economic benefits.

According to Barbara Murray, ILO disability specialist, a study of data in 10 Asian and African countries shows a loss of 3-7% of GDP when disabled workers are excluded from the workforce.

"It's very significant," she says, adding that her research supports claims that disabled workers have lower attrition and accident rates and that they even boost workplace morale.

Changing attitudes

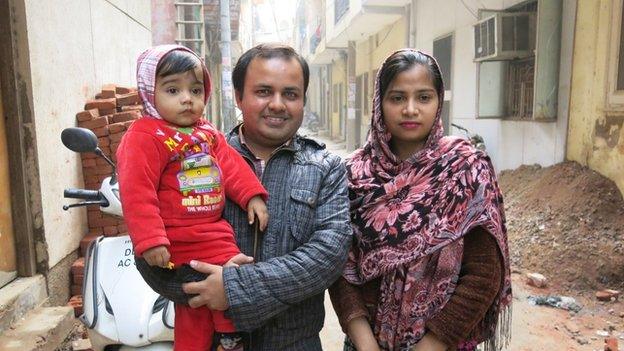

Mr Ali says that before he found work, he worried about being able to support his family

Meanwhile, Mr Ali is just happy to be working.

As his infant son, Azhar, plays in the home that Mr Ali shares with his extended family, he explains that before he found work he constantly worried about supporting them financially.

His younger brother, also born deaf, works at a KFC restaurant, also thanks to the Noida Deaf Society's help.

And while Haider Ali's monthly salary of $150 (£90) may not seem like much, it is good by Indian standards and a sign that negative Indian attitudes towards disability, at least in the corporate world, are slowly beginning to change.

- Published7 February 2014

- Published19 April 2013