What economic help for Ukraine?

- Published

Ukraine has a long history of poor economic performance

Events have moved rapidly in Ukraine over the last few days, but the uncertainty about the country's political and economic future remains.

There are also still doubts about who, if anyone, will provide the financial assistance Ukraine needs to avoid a default on its foreign debt.

But the changing political situation has been followed by tentative signs that Europe, the United States and the International Monetary Fund may be willing to provide financial assistance.

The country's finance ministry has said that $35bn (£21bn) will be needed over the next two years.

The European Union Commissioner for Economic Affairs, Olli Rehn, has said that substantial aid could be on the agenda. US Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew said the best approach would involve "international support through the IMF and bilateral support".

Ukraine does have a $15bn lending programme agreed with Russia, and has already received a first instalment - worth one-fifth of the total. But further payments from Russia are unlikely if Ukraine ends up with a government keen to turn towards the EU.

If the EU and the US were to fill the gap, they would almost certainly insist on a programme of policies agreed with the IMF.

But Ukraine's recent experience with the IMF has not been successful.

The previous lending programme, the IMF says, "went off track as the authorities stopped implementing the agreed policies".

In reviewing that episode, the IMF even went so far as to suggest that it might be useful for future IMF lending programmes to have "a mechanism to terminate off-track arrangements".

Energy woes

One central problem was Ukraine's reluctance to raise energy prices. It is a sector the IMF described as "opaque and inefficient". The subsidies impose an additional burden on stretched government finances and remove an incentive for households and businesses to use energy more efficiently.

Energy reform is also an important element in the association agreement negotiated with the EU. It was never signed by the former Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych, a decision which sparked off the protests.

So it seems a fair bet that any financial help from the West would require a commitment from Ukraine to cut those subsidies and move towards market prices for energy.

However strong the economic arguments for doing so might be, any Ukrainian government would find it a difficult move politically.

The problem could be especially acute if the Russian gas supplier, Gazprom, were to raise the price it charges Ukraine, and there has already been speculation that it might do so.

Gazprom officials have said there are no immediate plans along those lines.

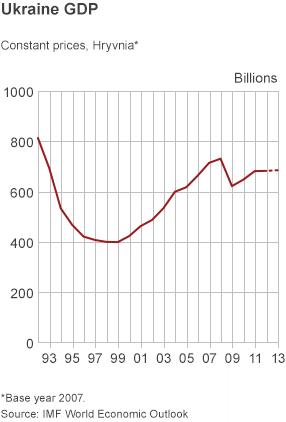

The background to Ukraine's current economic difficulty is a long history of poor performance.

When Soviet central planning came to an end and the Soviet Union broke up, the economies of the successor states contracted sharply.

Much the same happened to the Soviet satellites in central and eastern Europe.

Almost all have reversed the decline.

They have managed to grow beyond those pre-crisis levels, but Ukraine has not. Its economy is still smaller than it was in 1992.

Ukraine's economic burden

Poland provides a telling comparison. In 1992, using a method called purchasing power parity, their economies were similar sizes, Ukraine's being slightly the larger of the two.

Now Poland's economy is more than double the size of its neighbour's.

There are plenty of other measures that are very unflattering to Ukraine. It has a large current account deficit - that's trade in goods and services, together with some financial transactions.

Last year's figure was 8% of annual national income, GDP, and that is money that Ukraine in effect has to borrow from abroad. A deficit of that size can be manageable if international financial markets have confidence in the economic outlook.

If they do not, it may be a warning of trouble to come.

Last week, the credit rating agency Standard and Poor's downgraded Ukraine, reflecting its judgement that Ukraine would struggle to meet its debt payments without financial assistance, which was becoming increasingly uncertain.

It still is, though other possibilities, involving the West and the IMF, are tentatively taking shape.

Ukraine economic indicators compared

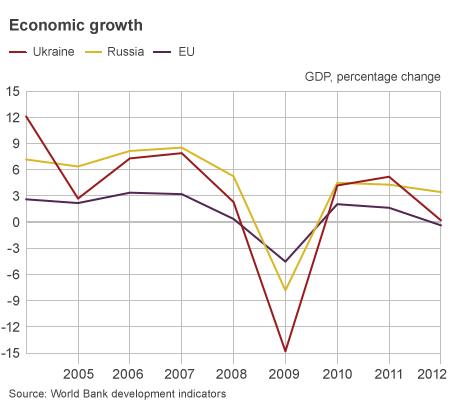

Ukraine's economic growth was severely affected by the global financial crisis of 2008 due to high foreign borrowing and a drop in the price of its top export, steel.

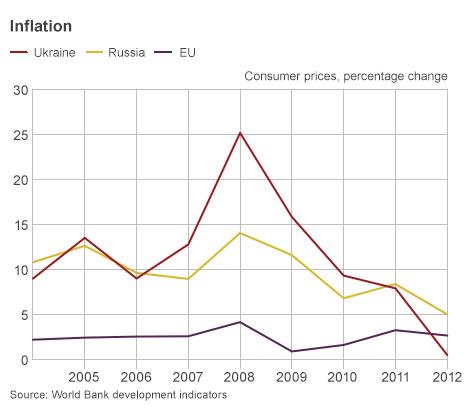

Rampant inflation took hold in 2008, driven by a spike in global food prices and energy price rises caused by a hike in the cost of imported gas.

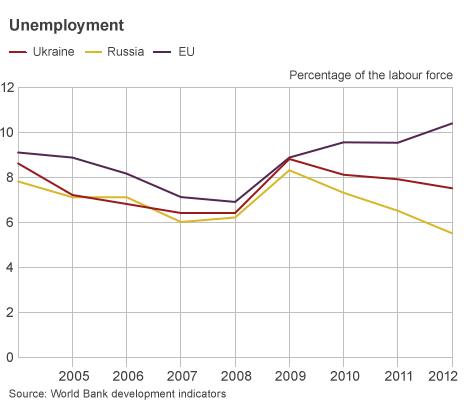

Unemployment appears to be less of a problem than in the EU but a high proportion of unregistered workers means that official figures do not show the whole picture.