The shadowy threat from China’s lenders

- Published

- comments

Linda Yueh reports on the unregulated lending ''explosion'' in China

Wenzhou juts out from China's eastern coast in Zhejiang province. Its wide, tree-lined streets, dominated by huge modern buildings, give no hint of the turmoil that has gripped its economy in the past couple of years.

Wenzhou has been at the forefront of China's experiments with private industry since reforms began over 30 years ago. As a result, its average income is double that of China.

But now it has gone wrong. Thousands in unofficial lending suddenly went unpaid. The Chinese central bank reports that 89% of households and 57% of firms have borrowed money, but not from banks.

A whole network of people and organisations threatened to come crashing down. There was a quiet rescue by the local government.

The source of this crisis was China's shadow banking system. Shadow banking is the slightly sinister name for trusts, leasing and insurance companies - or any other non-bank financial institution - which perform banking functions without a banking licence.

Shadow loans are estimated to make up 20% of all loans in China

Every country has unofficial lenders, but China's are in a league of their own. Individuals, companies - even local governments - who can't get loans from state-controlled banks have been on a borrowing binge from unofficial sources for years.

Now the concern is that the whole unstable pyramid is about to come crashing down, bringing the Chinese and perhaps even the global economy with it.

'Efficient but high rates'

For firms like Zhejiang Brothers Printing Company that operates a factory that prints decks of cards, borrowing from shadow banks is the only way that they can grow.

Zhou Feng, the 30-year-old boss, told me that without the high-interest loans from shadow banks he couldn't take on large orders. He usually pays 24-30% for these loans, which in his case are usually for just three to five days, and give him much-needed cash.

Zhou told me: "We still prefer to use shadow banking as a channel to get money to solve business problems as it's efficient and quick, though the rate is much higher than the banks… If the money can't arrive on time, we may have trouble."

Zhou says without shadow loans to buy materials, he wouldn't be able to deliver orders and therefore lose business

He admitted that it would be better to borrow from the bank, but added that up to half of the companies in Wenzhou were in the same position as his.

Following the crisis a short while ago, the government is now piloting a programme to get shadow loans registered. I was there on the first day of this amnesty for shadow bankers and borrowers. Unsurprisingly, no-one turned up.

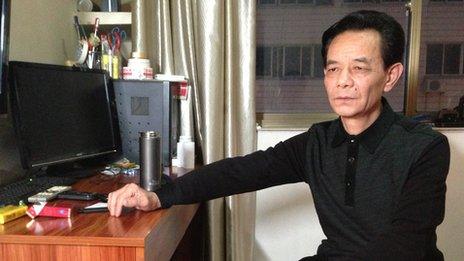

Still, Zhou Dewen, the local official in charge was convinced, and willing to admit, that shadow banking can be regulated, although it poses a significant risk.

"Shadow banking has reached a very high level. Without any law and supervision, such huge amounts of loans will pose a big threat," he said. "It's so risky and also has caused many crises."

Chinese official Zhou Dewen says shadow loans "pose a big threat"

Shadow banking for savers

So how big a problem are China's shadow banks?

This won't be reassuring, but the answer is no-one really knows. The shadow banking sector in China is largely unregulated by the banking authority, so although there are figures from the National Audit Office, they are likely to be less than precise.

Shadow loans are estimated to make up 20% of all loans. The Wenzhou official puts the figure at 3.7 trillion yuan ($604bn; £362bn) for the country. What is evident though is that if there were a banking crisis, there would undoubtedly be a massive impact on the economy, since debt is estimated to be more than 200% of GDP.

Wenzhou has been at the forefront of China's experiments with private industry

And it's not just loans. Savers are also affected by shadow banking.

These shadow banks and some not-so-shadowy banks also sell so-called wealth management products (WMPs), which offer returns that far outstrip the official deposit interest rate of 3%. But these are riskier and reminiscent of some of the horrifyingly complicated products sold in the US and Europe before the global financial crisis that started in 2007. How many are high-risk is unknown.

We spoke to one shadow banker who asked not to be identified. He told me that he charged interest rates of up to 100% and lent on average 6m yuan per month, which is just under £600,000.

"[The government] can never get rid of the borrowing in the society. So shadow banking will exist forever," he said. "They can only ban the very high-rate loans but can't ban all shadow banking. It's like gambling. Though gambling is banned in China, many people play cards or mahjong to gamble."

Worried victims

Sometimes, though, the authorities do crack down.

One of China's most notorious shadow bankers, Wu Ying, is now serving a life sentence in prison (a death sentence had been mooted). I met her father in his one-room bedsit. Outside, a group of victims gathered and shouted at him to return their money.

Mr Wu's daughter Wu Ying was arrested in 2007 and found guilty of cheating private investors out of 380m yuan

In another town, I met a victim who lost everything that her mother had saved to retire on. She lent the money to her boss to earn more interest than the meagre rate offered by the bank. His shadow banking operation collapsed and he later killed himself.

She told me: "I am more worried about what would happen to my mum if she finds out that she lost all her money and she can't accept that. She is too old and also has high blood pressure. She can't handle this kind of news."

The personal impact is huge - as are the consequences for the country.

The problem originates with the state-owned sector. The big four state-owned commercial banks and other mainly state-controlled banks account for nearly all official lending. Their customers tend to be state-owned firms. It means that there has been little scope for private banks - foreign banks account for less than 3% of total assets in the banking sector.

To address this, informal lending, which has existed for a long time in China, has grown rapidly in the past five years, because - extraordinarily enough - local governments also began to borrow from the shadow banking system.

During the midst of the global financial crisis the central government launched a spending programme of 4tn yuan to prevent a recession. However, rather than provide funding for this centrally, it left it to local governments to find the finance for these projects.

Bigger than Lehman?

If China were to have a banking crash, then the issue will be if the government can afford to rescue the banks without crashing the system.

If it can, then it is still a disaster since the cost to growth will be severe. If it can't, then China would be in crisis and the global consequences would be dire.

In some ways since every saver is affected in the world's most populous country, it could even have a bigger effect than the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

Either way, it's a troubling outcome.