Sunshine powers Uganda's school computers

- Published

A car with solar panels drives out to rural villages in Uganda to provide electricity for school computers

Turning on a computer shouldn't be that difficult. Except if you don't have any power supply.

Most rural schools in Uganda don't have mains electricity or any other reliable power, leaving them cut off from learning about modern technology.

So while the education world is awash with talk about technology and keeping up with the global race, many children at school in sub-Saharan Africa don't even get on the starting grid.

But a project serving rural schools in Uganda is taking a direct approach to the problem.

It's using the abundant equatorial sunshine to provide electricity for mobile classrooms, using portable solar panels.

Making connections

Run by an education charity, the Maendeleo Foundation, it's a relatively low-tech answer to a hi-tech gap.

The charge from solar panels provides power for an outdoor classroom

A sturdy vehicle drives to outlying schools, bouncing up and down along snaking, dusty, pot-holed roads, with solar panels attached like a photovoltaic roof rack.

These are not tarred roads, but bright red earthen tracks, pressed down by vehicles and villagers, goats and cattle, hemmed in by deep green vegetation, which is to say that this isn't exactly a motorway and it's slow progress.

When the jeep arrives at a school, it provides an instant pop-up classroom. There's a tent, chairs, desks and enough laptops for a class - and the charge from the solar panels allows the pupils to have a computer lesson lasting several hours.

The foundation has two jeeps, each going to five schools each week in rotation, reaching about 2,000 pupils.

Job opportunities

When the jeep arrives at Kyetume Church of Uganda Primary School, near Mukono, in central Uganda, it's like an emissary of the outside world.

It's not that the teachers and children here are unaware of technology and the internet, but apart from this project they cannot get their hands on it.

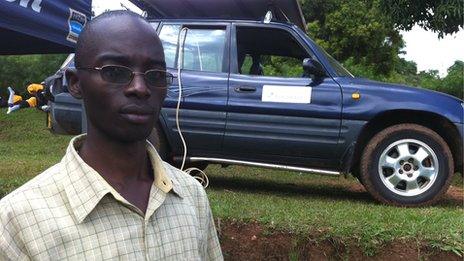

John Walusimbi says that young people need computer skills for future jobs

Once the laptops are plugged into a solar-driven battery, children tap away on learning games, much as they would anywhere else in the world.

Except this is an outdoor classroom and a green lizard sits on a hot stone watching them work.

John Walusimbi, a trainer with the project, says these computer lessons are essential for the future job chances of these rural youngsters.

"If children have these skills they won't be left behind."

Although laptops, tablet computers and internet access are now expensive in Uganda, he says that like mobile phones, they are likely to become more affordable.

Migrating to the city

When that happens these youngsters will be severely disadvantaged if they have never even taken their first steps in touching a computer.

"These skills are very rare in this community," says Judith Nankya, a teacher at the school. Without electricity, there is no computer in the school office or anywhere else for the staff to train.

Asia Kamukama says Uganda's young will have to compete with people around the world

There are wider infrastructure questions about why so few schools in Uganda have access to affordable electricity. Permanently installing and maintaining solar panels is also said to be too expensive for many schools.

And even when there is a connection to the electricity grid it can be unreliable.

Uganda has year-round sunshine and there's solar energy even on an overcast day. So for now, this is something that is reliable, self-reliant and works.

This is a lush, quiet place, not far from the shores of Lake Victoria. But many of these youngsters are likely to have to follow the path of migration from the country into the cities to look for work.

The Maendeleo Foundation's co-founder Asia Kamukama says that when these children leave school and begin working, they will have to "compete with people all over the world".

"Without prior introduction to these machines, they are afraid, they have nowhere to begin. We're preparing the next generation to know how to use computers," says Ms Kamukama, who was a finalist in last year's international education awards at the WISE summit in Qatar.

Soaring population

It isn't just about schools, she says that technology and the internet will be an important part of helping local communities to improve health and education services. It will give them information that other people take for granted.

The foundation is also working to provide online agricultural information for farmers in their local languages. It wants to provide information and improve skills.

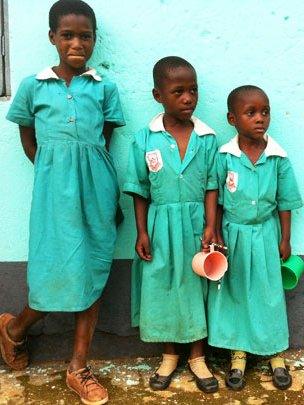

Growing population: Pupils at Kyetume Church of Uganda Primary School

This is being supported by a not-for-profit organisation called Electronic Information for Libraries, which makes digital information available in developing countries.

Uganda faces a huge challenge in providing skills for a population that is rising at a staggering rate.

When the country gained independence in 1962, the population was eight million. In 2012, it had quadrupled to 34 million and at the current rate of growth, it is forecast to almost quadruple again to 130 million by 2050.

That's like going from a population similar to Switzerland to a size similar to the UK and France combined.

What will all these young people do? Only about one in four currently gets a place in secondary school.

The capital, Kampala, is already overcrowded with young families in makeshift huts trying to scratch out a living. There are already more under-18 year-olds in the country than there are adults.

If there are millions more without the education and skills that could help them get work, it's going to raise big challenges for political stability.

It isn't just rhetoric to talk about youngsters having to compete in a "global village".

The outside influences are visible everywhere, whether it's Chinese factories and mobile phone adverts or English premiership football shirts.

There are competing cultures. This is a place where barracks have been named after Colonel Gaddafi and a stadium after Nelson Mandela.

The children trying out their solar-powered laptops are going to have to decide in which way they want to connect with the future.