Move over, GDP: How should you measure a country's value?

- Published

Poor GDP.

Everyone seems to be rounding on the once highly regarded economic measure.

Gross domestic product - a measure of the value of goods and services a country produces - is perhaps the most powerful statistical indicator in history, and has a huge influence on global policy.

Yet the main criticism of GDP, raised by none other than Bobby Kennedy back in 1968, is that it "measures everything... except that which makes life worthwhile".

In other words, it is hopelessly flawed as a yardstick of human welfare.

Indeed, as far back as the 1930s, Simon Kuznets, an early pioneer of GDP, warned that "the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income".

But despite several attempts at dethroning GDP, which rose out of the Great Depression and World War Two as an attempt to stabilise economic forecasting, the indicator remains the central measure of a country's success.

Ignoring economics

Enter the Social Progress Imperative, external, an organisation led by Harvard economist Michael Porter. It exists neither to bury nor praise GDP, but to complement it - by compiling an index which measures everything but economic output.

"If you strip out economic indicators," says Michael Green, the group's executive director, "[you can] look at the relationship between economic and social progress and understand it much better."

Mr Green, who worked in international development for many years, proposed the index together with the Economist's New York bureau chief, Matthew Bishop, at a World Economic Forum meeting.

The Social Progress Index (SPI) began by gathering data on 54 distinct welfare indicators, all of which broadly fell under three questions:

Does a country provide for its people's most essential needs?

Are the building blocks in place for individuals and communities to enhance and sustain wellbeing?

Is there opportunity for all individuals to reach their full potential?

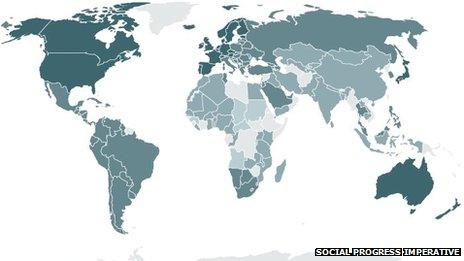

The resulting table, external, of the 132 countries from which robust data could be sourced, is perhaps least surprising at the top.

All the Nordic countries are in the top 10, along with advanced liberal democracies such as New Zealand, Australia and Canada.

Events like the unrest in Egypt could be easier to predict with the SPI

The second tier is much more interesting. It includes five members of the G7 - Germany, the UK, Japan, the US and France.

Japan's strength, for example, is in the area of basic human needs, but it fares below average on wellbeing and opportunity, and particularly low on tolerance and inclusion.

By contrast, the US scores low on basic human needs - it is 23rd in the world - but is fifth best at providing opportunity. And for a country that spends the most in the world on healthcare, the US performs badly on life expectancy.

Countries with the darkest colours on this map performed best on social progress

Arab Spring

Although much of the data gathered by the organisation has yet to be processed into meaningful conclusions, the index is providing some interesting lessons about the distinction between economic and social structures.

"Take the Arab Spring," says Mr Green. "You had a bunch of countries who were performing really well economically, and then suddenly this social collapse.

"Clearly a policy based simply on economic growth wasn't working for social harmony."

But a quick glance at the SPI shows the unrest might have been predictable.

Bobby Kennedy said GDP "does not allow for the health of our children... or the joy of their play"

"The north African countries all do worst on opportunity," Mr Green added.

"It wasn't necessarily material needs that weren't being met, it was the chance to take your life forward - rights, freedoms, choices, tolerance and inclusion."

GDP 'not destiny'

"Freedom," the famous Labour figure Nye Bevan once said, "is the by-product of economic surplus", but the SPI partly contradicts his theory.

While the index does show that extreme poverty and poor social performance go hand-in-hand, the correlation stops once countries reach a certain level of prosperity.

The bottom of the index is the preserve of struggling economies, but oil-rich countries such as Russia and Saudi Arabia also do very badly on social progress.

And New Zealand and Italy, who are very close in terms of GDP, are 29 places apart on the SPI table.

In other words, as Mr Green puts it, "GDP is not destiny."

There have been several other attempts at complementing or replacing GDP.

Sir Gus O'Donnell explains the impact wellbeing research is having on political policy.

The UN implemented the human development index, the OECD has a "better life index" and even the UK's own Office for National Statistics measures national wellbeing.

Recently, Sir Gus O'Donnell, a former senior civil servant in the UK, published a wellbeing and policy report, which investigated the main economic, social and personal drivers of happiness.

But the key strength of the SPI, Mr Green claims, is the number of different indicators it measures, and the fact that they can all - from religious tolerance to electricity supplies - be compared with GDP growth.

Take political economist Francis Fukuyama's famous problem of "getting to Denmark", by which he meant creating societies which mirrored the supposedly peaceful and prosperous Nordic states.

"You can say Denmark is happier than Britain, but what does that mean?" says Mr Green. "Do I have to speak Danish? Do I have to watch more episodes of Borgen?"

Analysing which SPI indicators correlate with a rise in happiness could help answer such questions.

But there are those who resist the idea that GDP cannot map welfare. Nick Oulton, of the London School of Economics, argues that economic growth can be a good measure of a country's wellbeing.

"It won't solve all problems, but a rise in wealth can lead to declines in infant mortality, increased life expectancy, and people getting healthier because they can afford to eat more food," he says.

The anti-GDP camp, he adds, are "in danger of prompting intrusive policies". It is almost as if they are saying "you might think you know what's good for you, but we know better", he contends.

Contrast and compare

Ultimately, the success of the SPI will be measured by one indicator - its effect on policy decisions.

Some countries are already taking notice. In July last year, Paraguay became the first country to officially start using the SPI as a basis for policy decisions.

Representatives from the Social Progress Imperative met Paraguay's president last year; the country has officially adopted the SPI

But the real utility of the index will come with comparisons to other data.

Plotting the SPI against government expenditure, for example, may help to finally settle the big versus small government debate.

Another test would measure income inequality against social progress, to test the "spirit level hypothesis" - does greater income equality foster health and happiness?

Meanwhile, experimenting with the data is something the Social Progress Imperative is very keen on indeed.

- Published31 July 2013