South Yorkshire's cutting edge technology

- Published

The AMRC facility is very much a collaborative space

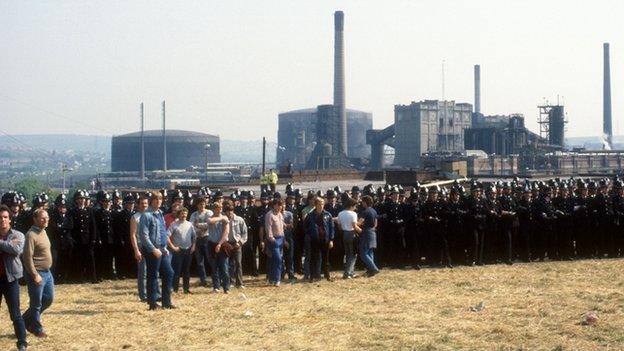

The Battle of Orgreave was one of the defining events of the bitter and divisive UK miners' strike of 30 years ago.

In June 1984 there were violent clashes between police and pickets at the Orgreave coking plant, near Rotherham in South Yorkshire.

Present were 10,000 striking miners and 5,000 police officers. More than 90 people were arrested, but the trial collapsed after 16 weeks.

The scars run deep. The Independent Police Complaints Commission is still investigating what actually happened, and whether there should be a new inquiry into the action of the police.

Now, 30 years on, the Orgreave site is utterly changed. Hundreds of new houses have sprung up in an estate called Waverley.

The rest, marked by two wind turbines, is a sleek new industrial estate devoted to what is called advanced manufacturing.

A series of large labs, workshops, and design studios built in the past 14 years, it bears a cumbersome name - the University of Sheffield Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) with Boeing. The aircraft-maker put considerable resources into the facility.

Elsewhere on the industrial estate, new factories are springing up. The most striking is a large Rolls-Royce plant, which will soon start producing "single crystal" fan blades for jet engines. They are much stronger than conventional ones, and able to function at far higher temperatures.

There will be 300 skilled engineering jobs at the Rolls-Royce centre.

Signs of a real manufacturing revival, after decades of relative decline in many industries.

Rich industrial past

Meanwhile, down the road in Rotherham there is the looming Magna Science Adventure Centre, a testimony to the wider Sheffield area's heritage as the steel capital of Britain.

School children troop in to marvel at the cavernous melting shop. Once an hour they can watch a simulated "big melt", which seemingly brings back to life one of the huge electric arc furnaces that dominated the former Steel Peech and Tozer steelworks.

AMRC seeks to pool together experience

Some 10,000 men were employed here in the decades up to its closure in 1993.

Now a handful of them show visitors round, full of good stories about the district's rich industrial past, and how this works began when two local 19th Century bookies made so much money from the horses they decided to invest a bit of it in steelmaking.

Since one of them was called Mr Steel, there seemed something inevitable about it. The company, changing hands many times over the years, eventually become an industrial giant.

But now its huge works are just an enormous memorial to a vanished past.

Nevertheless, as I discovered the other day, Sheffield's steel inheritance lives on in various ways.

Great tradition

The city has been a centre of British knife making for centuries. In William Chaucer's 14th Century poem The Canterbury Tales, the Miller carries a Sheffield-made knife.

Innovation in the 18th Century enhanced this reputation. The tradition continued with silvered Sheffield plate cutlery in the 19th Century.

Just over 100 years ago, a researcher in a commercial lab in Sheffield perfected stainless steel, giving a new twist to Sheffield's Steel City reputation. But over the decades since then, global competition has seriously eroded that once mighty reputation.

The site is now a world removed from how it looked back in 1984

What remains from the great tradition is considerable expertise in cutting equipment still absolutely vital to engineering processes. The Sheffield firms who have survived have learnt how to apply high technology and computer-controlled precision to the tools they have been making for many years.

And now the AMRC is finding new ways of using state of the art machines to save time and money in production processes.

The other day in another building on the campus called the Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre they were installing a vast boring machine costing hundreds of thousands of pounds.

It will be used to perfect the speedy drilling of very accurate holes needed in Britain's new nuclear reactors, if, that is, the orders for them are ever placed.

All this public money spent on machines and research induces a nagging question - why cannot the huge engineering companies who partner with AMRC do the research themselves?

They have invested in similar machinery, after all. They are using it all the time.

The answer is a revealing one. Advanced manufacturing needs lots of corporate capital. Invest in such a machine and you can't afford to experiment with it once it goes into production.

But the AMRC researchers are paid to do that, sharing the results with partner companies large and small, and, it is hoped, creating new opportunities and jobs in British businesses.

Competitive advantages

Much of the work is too highly technical readily to be explained to non-engineers.

But we stopped at what looked like a thick titanium bus wheel lying on its side.

In fact it was the rotor disc at the centre of the famous Rolls Trent jet engine. The disc has some 20 slots into which the fans of the engine are fitted, an assembly that has to withstand very high temperature and pressure.

Each slot used to take 54 minutes to gouge out of the resistant titanium block. Thanks to AMRC research work on cutting tools, lubricants, software and machining techniques, the same job can now be done in 90 seconds.

Remarkable savings in the time it takes to make each engine, and big competitive advantages for the manufacturer.

There in a nutshell - or a jet engine slot - is advanced manufacturing. Improvement by improvement, detail by detail, over and over again.

With millions invested in the site where they fought the Battle of Orgreave, Sheffield University and its backers are hoping they will find many more ways of helping British manufacturing to thrive and prosper, two centuries after the British industrial revolution changed the way the world worked for the first time round.

Peter Day reports from Sheffield in the first of a new BBC Radio 4 series of In Business on Thursday, 3 April at 20:30, repeated on Sunday, 6 April at 21:30.