How 3D printing is changing the shape of lessons

- Published

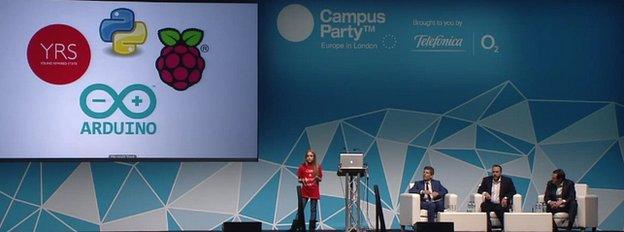

Amy Mather, a young pioneer of designing with 3D printer technology

There have been dramatic headlines about 3D technology, encompassing ideas to use 3D printers to make clothes, food, firearms and the parts of a house.

It's also making an impact on education, with plans to put 3D printers into schools in the United Kingdom and the United States.

These technologies hold massive potential for young people both in and out of school.

Schools are getting interested in this "rapid prototyping" technology. But there are still the usual barriers - access, funding, teacher awareness and confidence.

However, many learners are getting 3D design whether or not their schools are ready.

One of the most illuminating advocates is a 14-year-old schoolgirl from Manchester in the UK.

Amy Mather won the European Commission's first European Digital Girl of the Year Award last year.

The schoolgirl has presented her ideas in front of expert audiences, including Campus Party at London's O2 Arena, Wired Next Generation and the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts (RSA).

'Digital maker' movement

Amy got involved in coding and later 3D design after attending the Manchester Science Festival when she was 11.

But the key inspiration for her work has been what is loosely termed the "digital maker" movement, a global drive to encourage young people to be creative with technology.

This includes support from Fab Lab in Manchester. "Fab lab" stands for a "fabrication laboratory", where digital ideas are turned into products and prototypes.

Learning from the young: Amy Mather presents her ideas on 3D printing

The Fab Lab holds open days for the public and these allowed Amy to use software and hardware not available in her school, such as 3D printers and laser cutters.

She uses 3D design and manufacturing techniques for her school GCSE product design coursework.

"There are people always on hand with experience, people who live and breathe it," she says. "And there is a great community spirit so it's really, really easy to learn there and to go at your own pace and experiment."

'Fab Labs'

Manchester's Fab Lab was the first of nine in the UK, with the number expected to rise to 30 within three years.

They are part of a global project which started in the US, growing from a university course, "How To Make (Almost) Anything", created by Professor Neil Gershenfeld, director of the Centre for Bits and Atoms at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US.

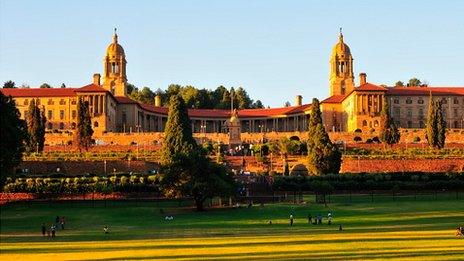

Students in Pretoria have designed their own 3D printer for schools in Africa

Within eight years of publishing his seminal book, Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop - from Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication, there are now around 200 Fab Labs in more than 40 countries.

Prof Gershenfeld's view is that the digital revolution has already happened and that we are in process of seeing it put into practice.

The challenge for Fab Labs, he says, is to harness the "inventive power of the world" and to apply it to "design and produce solutions to local problems".

The Fab Labs serve both education and business as places where interested parties can come together to work with the technology. And Prof Gershenfeld is vocal in resisting the media's hyping of 3D printing.

Amy Mather reflects that "get on with it" attitude. It's also a phrase that comes up regularly in conversation with her.

She's also not the kind of person to wait until she can get her hands on the most up-to-date technology.

Three-dimensional DIY

Why wait for access to a 3D printer if you can use other methods for construction?

She describes how she used 3D design software to make her own flat-pack version of a stool - and then used a machine to cut out the pieces so that she could assemble the final product.

Face of the future: 3D printing is changing the design process for students

She has used laser cutter technology to make cases for the computers she uses for her projects and has even used a 3D printer to design a vacuum-formed chocolate mould for a friend's birthday party.

Unfortunately the edges were too sharp, she concedes. "But I will try again with thicker, food-safe plastic."

"What I really like is that you can make very intricate designs," she adds.

"Most of the software is very easy to use, very intuitive. With just a couple of online tutorials, it's really easy to learn how to get around it."

There are free, open-source systems which allow pupils to cut from a flat sheet and then assemble a 3D model.

This improved ease of use and lower pricing are also highlighted by Martin Stevens and his partner Trupti Patel whose company, It Is 3D, has pioneered work with schools in the UK.

Entry-level printers have moved on from the kits that have been adopted by more confident teachers with advanced students, he says.

And there are now plug-and-play machines that work "out of the box", with the kind of reliability and robustness that schools need.

Experience has made Martin Stevens wary of government schemes that often get hardware into schools where it remains unused, so his priority has been to create a full range of online video support materials to familiarise learners and teachers.

Some students are showing extraordinary independence.

Pieter Scholtz and Gerhard de Clercq, 15-year-old students at Menlopark High School in Pretoria, South Africa, built their own 3D printer with a mobile phone app.

It is their contribution to making rapid prototyping mobile for African schools where PCs are in short supply.

"We can recycle cola and soft drinks bottles to make 3D printing filament as our raw material for our machine," they say. "We can even use that material to 3D print a prosthetic arm."

3D printing goes freehand

Amy Mather is keeping a close eye on new developments. She's currently taken with the notion of freehand 3D printing being offered by a new invention, the 3Doodler, which is described as "the world's first 3D printing pen".

It doesn't need a computer or printer. "You put plastic rods in it and it works a bit like a glue gun," she says.

"It heats up the plastic and extrudes it through its nib and you can draw 3D items with it. You can either draw it first on a flat surface and then assemble it, or you can draw straight up into the air.

"It's good for quickly prototyping ideas and being creative but it's nowhere near as expensive as a 3D printer and you don't have to have the knowledge of any CAD [computer aided design] software.

"You can just get on with it and do what you like, swap and change colours and things. I think that's a very useful tool."

Her next ambition is trying to set up her own "Mini Maker Faire", in this case a Mini Mini Maker Faire.

"We would invite under-18s and have mentors who can show them how to use technology like laser cutters, CAD software and CAM [computer aided manufacturing) machinery.

"You get them to create whatever they want and at the end they put on an exhibition, showing their work to the public and how proud they are of it."