How GDP became the figure everyone wanted to watch

- Published

The economist, author and BBC Trust deputy chairman, Diane Coyle

In my confused head I always get the celebrated economist Diane Coyle muddled up with the celebrated domestic economist Nigella Lawson.

There's a good reason for my muddle. Years ago, I appeared alongside Ms Coyle on a late-night BBC Radio 2 programme hosted by Nigella Lawson's first husband, the late John Diamond.

I can no longer remember what the topic was, but I do remember the technique Mr Diamond devised to prevent the conversation lapsing into the incomprehensibly technical.

Every time one of us said something he considered to be jargon, he would halt the exchange by tapping his water glass with a neat little "ting", and we would have to backtrack and explain in words of one syllable. A very useful technique that should be universally observed.

Anyway, Ms Coyle has gone up in the world, and she is now deputy chairman of the BBC Trust. (She is also married to my colleague Rory Cellan-Jones, the BBC News technology correspondent, but that is another story.)

Ms Coyle's BBC connections maybe make it difficult to comment on her new book, but its subject is an important one.

It's called GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History: you can almost hear John Diamond tinging his glass already.

Ms Coyle runs a consultancy called Enlightenment Economics, and writes nifty books with titles such as The Economics of Enough and The Soulful Science: What Economists Really Do.

She manages to think in mostly words of one or two syllables, earning the approval of people such as Mr Diamond.

Her book on gross domestic product (GDP) is small and unintimidating. Despite the pass-me-by subject, it is interesting and important, particularly when it comes to the emphasis now given to GDP, and the inadequacies of this now time-honoured measurement of how our economies are doing.

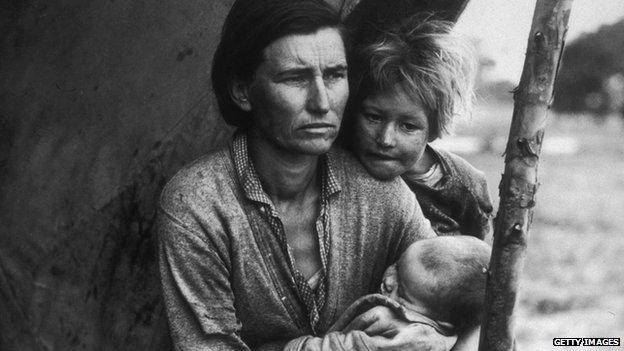

The Great Depression increased the focus on making GDP statistics more accurate

From the attention it gets in press and broadcasting, GDP seems to rule our lives, says Ms Coyle. But hardly anyone appears to understand it.

With clarity and precision, she explains its strengths and weaknesses.

War effort

GDP sort of emerged in the 17th and 18th Centuries as a way of trying to measure what states could spend on their wars... hence the word "statistics".

The need for better and more-frequent-than-annual figures emerged from the disjunction of the Great Depression of the 1930s, and then World War Two.

In both the UK and the US, pioneer economists started gathering data more than merely annually to help their governments plan recovery and then war.

Out of this emerged the modern concepts of gross national product and gross domestic product, bringing public spending into the total picture for the first time.

After World War Two, with much government social and political intervention, the quest for data became ever more intense, and distorting.

Disasters lead to the situation where economic growth quickens because GDP measures the recovery effort, ignoring the destruction of assets that made recovery necessary.

In the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, GDP boomed, along with the babyboomers: a society consuming mass entertainment, mass travel and mass communications.

International comparisons began to be asked for. National statistics were standardised, and GDP became the rule-of-thumb way of comparing the performances of capitalism and communism.

Happiness measure

But the more we learned about economies, the more we wanted to know.

What about the data left unmeasured, such as the informal economy of people paying cash and escaping the tax system, or the status of investments?

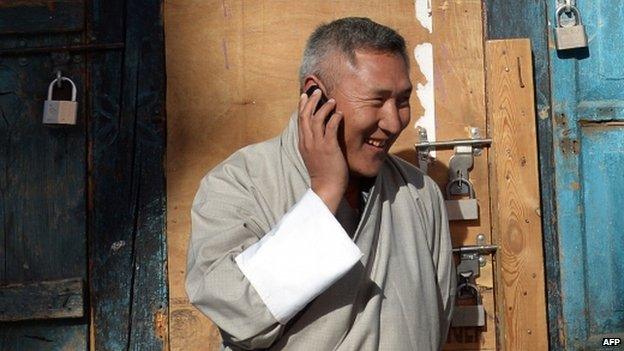

Bhutan tries to measure how happy people are in the country

And what about electronic data becoming a huge part of the modern economy, but still very unrepresented in the GDP calculation?

Also, there is household work, what the Americans call homemaking.

An ever increasing output of physical goods with monetary value attached to them is one way of measuring society, but an awful lot is left out.

How do you really measure well-being, the impact on the environment of ever increasing consumption... and of course, human happiness?

The kingdom of Bhutan made this last factor a key indicator, but other nations have held back. It is just possible that grumbling is a luxury granted only to the (relatively) better off. The best things in life are not easily measured.

Meanwhile, economics has become a popular sport, and economic growth has become a mantra. Growth is good, imply the headlines, decline is bad.

More is very good: more stuff, more profits, more consumption, more choice. More everything is the default measurement of success... for companies, for politicians, for headline writers, for hardworking families, for everyone.

One moment's thought will reveal the inadequacy of all this, but growth as measured by GDP is fairly easy to grasp, even when it is expressed in nonsense terms of nought-point-one or two per cent more than expected. As if anyone really knows.

Meanwhile, the world was lulled by the rapid GDP expansion of the early 2000s and complacency lured it into something close to economic disaster in 2007, and after the event new questions were asked about our conventional view of how the economy worked.

Asked, but not answered, as we look to growth to get us out of the mess that concentrating on growth produced in the first place.

Oversimplification?

Ms Coyle concludes her surprisingly diverting romp through the history of GDP with a sharp conclusion.

"At present," she says, "we are in a statistical fog, without the information needed about either the negative aspects of growth, when it is unsustainable and depletes the natural and other assets available for the future, or the positive aspects when it delivers innovations and creativity.

"GDP, for all its flaws, is still a bright light shining through the mist."

That may be so for professionals, but for the rest of us GDP is an oversimplification of something it is probably dangerous for us to know too much about, lest we find ourselves (in the words of JM Keynes) "in the thrall of the ideas of some long-dead economist".

More, better, bigger is not necessarily best, and we are going to have to realise how to cope with that realisation, especially when it comes to those headlines about GDP.

Every quarter a venerable independent think tank, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), publishes a much pored-over quarterly review of the economy.

Twenty years ago on the inside cover of every issue there would appear a remarkable health warning that everyone involved in the business of economics should still read, mark and learn.

It said: "The workings of the economy are not fully understood, and even if they were, economic prediction would remain hazardous because of the impact of political events and technological developments.

"Nevertheless, the institute believes that a group of economists, presenting a comprehensive account of current economic developments and a coherent view of likely trends, can provide a useful service."

Delicious modesty, now rather unfashionable in public or private life. Under its current director Jonathan Portes, the NIESR takes a similar stance.

I can just hear John Diamond pinging his water glass in acclaim.