Methane hydrate: Dirty fuel or energy saviour?

- Published

Methane hydrate, or fire ice, is a highly energy-intensive fuel source

The world is addicted to hydrocarbons, and it's easy to see why - cheap, plentiful and easy to mine, they represent an abundant energy source to fuel industrial development the world over.

The side-effects, however, are potentially devastating - burning fossil fuels emits the CO2 linked to global warming.

And as reserves of oil, coal and gas become tougher to access, governments are looking ever harder for alternatives, not just to produce energy, but to help achieve the holy grail of all sovereign states - energy independence.

Some have discovered a potential saviour, locked away under deep ocean beds and vast swathes of permafrost. The problem is it's a hydrocarbon, but quite unlike any other we know.

Huge reserves

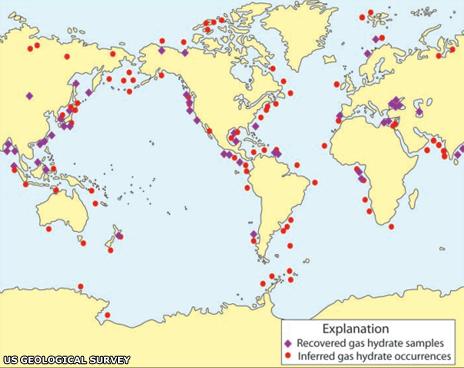

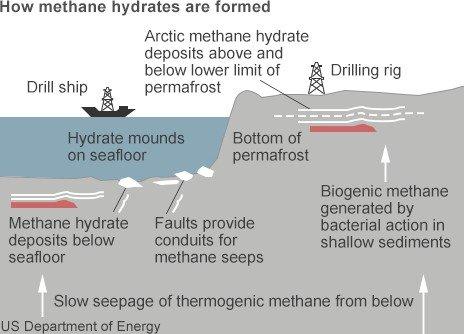

Otherwise known as fire ice, methane hydrate presents as ice crystals with natural methane gas locked inside. They are formed through a combination of low temperatures and high pressure, and are found primarily on the edge of continental shelves where the seabed drops sharply away into the deep ocean floor, as the US Geological Survey map shows.

And the deposits of these compounds are enormous. "Estimates suggest that there is about the same amount of carbon in methane hydrates as there is in every other organic carbon store on the planet," says Chris Rochelle of the British Geological Survey.

In other words, there is more energy in methane hydrates than in all the world's oil, coal and gas put together.

By lowering the pressure or raising the temperature, the hydrate simply breaks down into water and methane - a lot of methane.

One cubic metre of the compound releases about 160 cubic metres of gas, making it a highly energy-intensive fuel. This, together with abundant reserves and the relatively simple process of releasing the methane, means a number of governments are getting increasingly excited about this massive potential source of energy.

Technical challenges

The problem, however, is accessing the hydrates.

Quite apart from reaching them at the bottom of deep ocean shelves, not to mention operating at low temperatures and extremely high pressure, there is the potentially serious issue of destabilising the seabed, which can lead to submarine landslides.

A greater potential threat is methane escape. Extracting the gas from a localised area of hydrates does not present too many difficulties, but preventing the breakdown of hydrates and subsequent release of methane in surrounding structures is more difficult.

And escaping methane has serious consequences for global warming - recent studies suggest the gas is 30 times more damaging than CO2.

These technical challenges are the reason why, as yet, there is no commercial-scale production of methane hydrate anywhere in the world. But a number of countries are getting close.

'Enormous potential'

The US, Canada and Japan have all ploughed millions of dollars into research and have carried out a number of test projects, while South Korea, India and China are also looking at developing their reserves.

The US launched a national research and development programme as far back as 1982, and by 1995 had completed its assessment of gas hydrate resources. It has since instigated pilot projects in the Blake Ridge area off the coast of South Carolina, on the Alaska North Slope and offshore in the Gulf of Mexico, with five projects still running.

"The department continues to do research and development to better understand this domestic resource... [which we see] as an exciting opportunity with enormous potential," says Chris Smith of the US Department of Energy.

The US has worked closely with Canada and Japan and there have been a number of successful production tests since 1998, most recently in Alaska in 2012 and, more significantly, in the Nankai Trough off the central coast of Japan in March last year - the first successful offshore extraction of natural gas from methane hydrate.

'Game changer'

Of all the countries actively researching methane hydrate, Japan has the greatest incentive. As Stephen O'Rourke, of energy consultants Wood Mackenzie, says: "It is the biggest importer of gas in the world and has the highest gas import bill as a result."

However, he points out that at just $120m (£71m; 87m euros) a year, the Japanese government's annual budget for research into gas hydrates is relatively low.

The country's plans to establish commercial production by the end of this decade do, then, seem rather optimistic. But longer-term, the potential is huge.

"Methane hydrate makes perfect sense for Japan and could be a game changer," says Laszlo Varro of the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Elsewhere, incentives to exploit the gas commercially are, for now, less pressing. The US is in the middle of a shale gas boom, Canada also has abundant shale resources, while Russia has huge natural gas reserves. In fact, Canada has put its research into methane hydrate on hold, and deferred any additional funding.

China and India, with their rampaging demand for energy, are a different story, but they are far behind in their efforts to develop hydrates.

"We have seen some recent progress, but we don't foresee commercial gas hydrate production before 2030," says Mr O'Rourke.

Indeed, the IEA has not included gas hydrates in its global energy projections for the next 20 years.

'Mad Max movie'

But if resources are exploited, as seems likely at some point in the future, the implications for the environment could be widespread.

It is not all bad news - one way to free the methane trapped in ice is pumping in CO2 to replace it, which could provide an answer to the as yet unsolved question of how to store this greenhouse gas safely.

But while methane hydrate may be cleaner than coal or oil, it is still a hydrocarbon, and burning methane creates CO2. Much depends of course on what it displaces, but this will only add to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Methane hydrates are found mainly under ocean seabeds and Arctic permafrost

However, this may be a far better option than the alternative. In fact, we may have no choice.

As global temperatures rise, warming oceans and melting permafrost, the enormous reserves of methane trapped in ice may be released naturally. The consequences could be a catastrophic circular reaction, as warming temperatures release more methane, which in turn raises temperatures further.

"If all the methane gets out, we're looking at a Mad Max movie," says Mr Varro.

"Even using conservative estimates of methane [deposits], this could make all the CO2 from fossil fuels look like a joke.

"How long can the gradual warming go on before the methane gets out? Nobody knows, but the longer it goes on, the closer we get to playing Russian roulette."

Capturing the methane and burning it suddenly looks like rather a good idea. Maybe this particular hydrocarbon addiction could prove beneficial for us all.