The unlikely debt capital of Britain

- Published

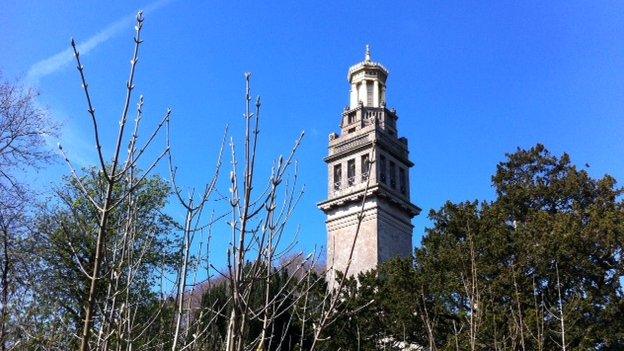

The 120ft-high Beckford's Tower is a landmark at Lansdown Hill, Bath

Beckford's Tower stands proudly on the hills overlooking the spa city of Bath, a monument to eccentricity and wealth.

The 120ft-tall Neoclassical structure was built in 1827 as a retreat for writer William Beckford, who once said: "I am growing rich, and mean to build towers."

Residents in the area, called Lansdown, may not share his love of the high-rise but many mirror his high finance. This is an affluent area.

So it comes as quite a surprise that this has been named the debt capital of Britain.

The BA1 9 postcode area has the highest level of personal loans per person in Britain. Each owes an average of £2,311, according to the latest data, external from the British Bankers' Association (BBA).

Are these figures as much of a folly as the local landmark, or does the data actually tell us something of the nature of debt in the current economic climate?

Asset-rich

The BA1 9 postcode area covers Lansdown, a suburb of Bath, as well as the nearby villages of Kelston and North Stoke.

Within its boundaries are Lansdown Golf Club. Full annual membership will set you back £784.

It also takes in Bath racecourse, where a number of gamblers may have fallen into debt a little quicker than they ever thought possible.

Yet the local Conservative councillor for the area, Patrick Anketell-Jones, says: "I have had no reports of destitution in the area. I've never considered [debt] as a problem in the ward."

His theory for the BBA's findings is that Lansdown, a Victorian extension of the city of Bath, has a number of large detached homes with huge gardens. It can be fairly easy to borrow from banks when you own such a valuable asset.

Many people have used personal loans to buy a car

Danny Sacco, manager of Lansdown Mazda - a new and second-hand motor dealership - says plenty of locals are buying cars from him.

He sold 72 new cars last month, a record for March, and describes the market as "buoyant" at present.

Significantly, he adds that 82% of purchases are made on credit. Drivers, he says, are taking advantage of 0% finance deals that mean there is not much point paying the full price up front.

"There was a lot of pent-up demand," he says.

"Cars are a good barometer of the economy. We've got more than just green shoots. People are optimistic."

Complex data

Now the rate of pay increases has caught up with the inflation rate (which charts the rising cost of living) for the first time for years, both men are suggesting that people are more confident to borrow.

A personal loan is an example of this. You need a decent credit rating to get one, and the bank or building society needs to be sure you will be able to pay it back.

These loans are generally not the choice of those stretched to financial breaking point. Credit unions, payday loans or overdrafts are more likely to serve the less wealthy.

Personal loans only give a partial picture of debt. And, in fact, the BBA data only covers 60% of the personal loan market in Britain.

The data is not drawn from every lender, just Barclays, Lloyds Banking Group, HSBC, RBS, Santander, and Clydesdale and Yorkshire Banks.

It is the second time the figures have been published, and although they are becoming more comprehensive, the BBA warns there is a danger of reading too much into figures from each particular area.

"This data is complex and it remains very difficult to draw firm conclusions about lending at a local level," says Richard Woodhouse, the BBA's chief economist.

Signs of recovery?

Lansdown Hill has magnificent views over the city of Bath

Still, the geographical breakdown of lending is important. This data shows where nearly £30bn of personal loans are owed across the country.

It also gives an area-by-area breakdown of £901bn of outstanding mortgage debt, revealing that 44% of this is owed in London and the South East of England where house prices are the highest and average earnings are the biggest.

For some, increasing debt is a sign of trouble, especially for personal finances. However, it also tends to rise when the economy is stronger.

Over recent years, the BBA's own data shows that repayments to High Street banks of loans and overdrafts have regularly outstripped new borrowing. It was the opposite situation, by far, before the recession. For example, in February 2006, new borrowing outstripped repayments by £1.1bn.

In a more vibrant economy, banks would show greater willingness to lend and individuals greater willingness to take a risk and borrow to buy a car or build a new extension to their home.

So the next time you visit the picturesque city of Bath, and pay £3.20 to take the park-and-ride bus down Lansdown Hill, you can decide whether you are looking at an area gripped in the vice of credit, or one where the residents are feeling bold enough to borrow.

Or perhaps, at a weekend, you might decide to climb the steps of Beckford's Tower to see what Britain's personal loan hotspot looks like, if only to conclude that his wealth bought him the most magnificent views.