Obama, Abe and a high-stakes trade deal

- Published

- comments

.jpg)

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and US President Obama are looking to iron out their differences over the ambitious Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal

Trade deals don't usually take centre stage at summits among world leaders. But the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is at the forefront of US President Barack Obama's first state visit to Japan.

Both leaders hope it will serve their own purposes: it is how President Obama can make his so-called "Asia Pivot" more concrete than just an aspiration, and how Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe can put some substance to the structural reforms within his ambitious plan dubbed "Abenomics".

Firstly, the US and Japan are the main negotiators of the TPP, which includes 10 other nations from around the Pacific Rim: Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Chile and Peru.

These countries account for nearly 60% of global GDP and over a quarter of world trade.

In other words, it would create the biggest free trade area in the world if successfully concluded, and it's estimated it would add over $200bn (£119bn) per year to world GDP by 2025.

The US calculates that the TPP would add $305bn in exports per year globally, with nearly half accounted for by an increase in US exports by an additional $123.5bn.

How will US trade deal affect Japan's economy? Linda Yueh reports

The Pivot

So, if this were solely an economic matter, excluding China - the biggest market in Asia - wouldn't be sensible. Yet, the TPP does just that.

As the US continues to be involved in crises in the Middle East and Ukraine - including negotiating yet another free trade agreement with the EU - there is little to show thus far for the Asia Pivot that had been described as the centrepiece for Obama's second term.

President Obama's Asia Pivot isn't supposed to be solely about geo-politics, but also a deeper rebalancing towards fast-growing Asia to boost America's economy. Securing preferential access to Asia's markets benefits US companies over Chinese firms that won't be part of the market-opening measures of the TPP.

This way, excluding China doesn't look just like politics or even containment, but rather that the world's second largest economy doesn't yet have the market-based economy, such as a flexible exchange rate or open capital accounts, to be part of the new free trade area.

The end result of excluding China is the same, but the framing looks more appealing.

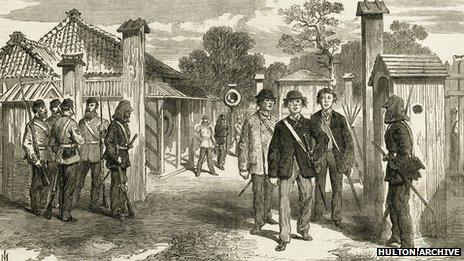

The second opening of Japan

Japan first opened to the West in the 1800s, which ushered in a period of growth

For Japan, the stakes are even higher.

The long-awaited "third arrow" of Abenomics - or the structural reforms to increase competitiveness that ultimately are what raises growth - has been somewhat lacking.

In an op-ed piece, external, headlined "The Second Opening of Japan", Prime Minister Abe says that the Pacific Rim economies encompassed by the TPP is a growth centre which "will continue to propel Japan's economy for the foreseeable future".

The TPP is estimated to raise Japanese per capita GDP by about 1.5%, which would nearly double the slow pace of expansion the country has experienced in the past two decades.

It would also raise per capita growth to over 2%, essentially lifting the country out of its long stagnation.

The two giants and the farmers

Japan has faced significant opposition from farmers over its plans to join the TPP

There are certainly high expectations, but it doesn't mean that the process will be smooth sailing or that the TPP will be concluded any time soon.

Of the nations negotiating the TPP, the only one that doesn't already have a free trade agreement (FTA) with the US is Japan. So, the two nations - in addition to being the main players — are the key and also the main obstacles.

One academic has described the TPP negotiations as being between "two giants and the rest".

The reason why there hasn't been an FTA between the world's biggest and third largest economies - or even when Japan was the second largest - is because of protectionism of key sectors.

In Japan, five "sacred" agricultural products of rice, beef/pork, dairy, wheat, and sugar are protected. For example, Japan has a 778% tariff on imported rice.

Conversely, the US protects its car market - and the Japanese are demanding more access.

Reform agenda

These are perennial issues, but the TPP could help to provide political cover for Mr Abe's intended economic reforms.

He is trying to abolish a policy which has been in place since 1971, that keeps rice prices high and has cost the economy an estimated 8 trillion yen ($78bn). The TPP could even force Japan to cut its tariff on imported rice.

Of course, agriculture in the US isn't without its share of problems. The Americans are also looking to reform their own farm bill which is set to cost $1 trillion over a decade.

The top 10% of the largest farm businesses receive 75% of the government subsidies, while average farm household incomes exceed the average by a whopping 25%.

It's not hard to see why agricultural subsidies are often called subsidies for the wealthy.

Tough sell and positioning

So far, trade negotiations have come to an impasse, raising the possibility that there won't be a big announcement during the Obama-Abe summit.

But it is in the economic interests of both the Americans and the Japanese to get an agreement done.

By premising so much of the Asia Pivot and Abenomics on the TPP, the stakes are certainly high.

As the politics are also overlaid with geo-politics vis-a-vis China, it will not only be a tough sell but a tricky one to position.