Fossil fuel subsidies growing despite concerns

- Published

Petrol is subsidised in many countries around the world, such as Indonesia

Government subsidies for renewable energy cause great consternation to those who believe in the sanctity of free markets.

"If they can't stand on their own feet, then why support them?" the argument goes.

But in actual fact, most energy sources are subsidised, and none more so than fossil fuels. Indeed in straight numerical terms, subsidies for oil, coal and gas far outweigh those for renewables.

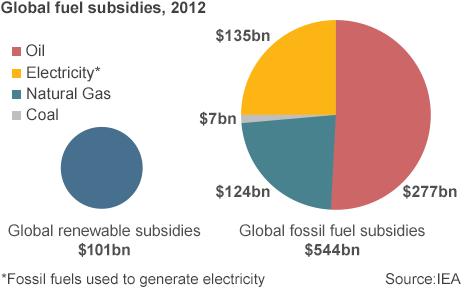

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in 2012 global fossil fuel subsidies totalled $544bn (£323bn; 392bn euros), while those for renewables amounted to $101bn. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) puts the total for hydrocarbons nearer $2 trillion.

Fossil fuels may account for 80% of our total energy consumption, but they hardly represent a nascent industry in need of a helping hand.

'Vigorous competition'

The subsidies come in many different forms, which helps to explain the massive discrepancy in estimates - the IEA focuses on subsidies that have a direct impact on the consumer, whereas the IMF includes those aimed at producers, such as tax relief and the cost of carbon.

Some argue that certain producer subsidies are both necessary and beneficial. "They encourage vigorous and healthy competition for natural resources that might otherwise be uneconomic to exploit," says Philip Whittaker at the Boston Consulting Group.

He argues these kinds of subsidies are simply "modifications" to a global energy market that is "to some degree, an artificial construct". In other words, there is no level playing field even without state support.

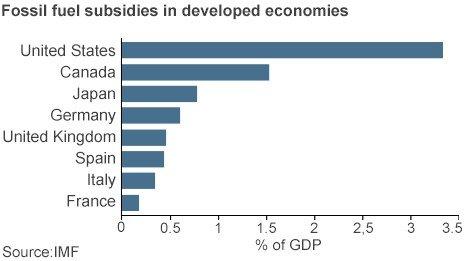

But the majority of subsidies relate to consumption rather than production, even in developed economies - as much as two-thirds of the average $55bn-$90bn a year in subsidies handed out by countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

There are numerous types of consumer subsidies, ranging from lower tax rates and wage subsidies to cash handouts and undercharging for government services.

In the UK, for example, value added tax (VAT) on gas and electricity is 5% rather than the 20% charged on most other goods, while according to the German Wind Energy Association, direct financial aid to the German coal industry totalled more than 200bn euros between 1970 and 2012 - subsidies that will only be phased out in 2018.

'No sense'

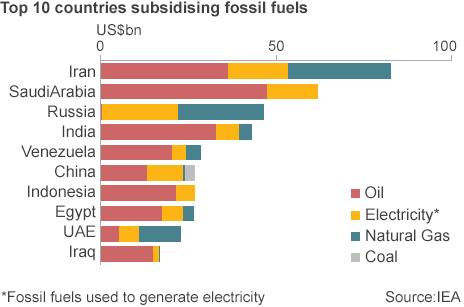

But most subsidies are handed out in developing economies in the form of state investments at very low rates of return, and lost income from selling fuel at an artificially low price.

For example, as Laszlo Varro at the IEA explains, a $100bn investment in electricity infrastructure at a 2% rate of return, where the cost of capital on the open market would be 8%, represents a $6bn subsidy.

Equally, selling a barrel of oil domestically at $20 to keep petrol prices low when you could export that same barrel at the open market price of $100 represents an $80 subsidy.

As William Blyth at Oxford Energy Associates says: "Economically, this doesn't really make any sense."

Massive investment

There are many reasons why. For a start, subsidies stifle private investment in the energy sector, as companies cannot compete with low, government-subsidised prices. And most governments cannot afford to provide cheap power to their entire population, let alone efficient power generation to parts of it.

The IEA has estimated a $1tn dollar investment is needed in the Indian power sector in the next 20 years to help bring electricity to the 300 million people who currently have no access to it. The government simply cannot afford this kind of money.

And the same story is true, albeit on a smaller scale, in Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines and much of sub-Saharan Africa. In fact half of the developing world's electricity sector is state-owned.

As Mr Varro says: "With the exception of the Middle East, it is not realistic for governments to underwrite these kinds of investments."

Subsidies also absorb money that could be spent on other priorities such as health and education, not just by draining government coffers but by significantly reducing tax revenues. According to the IEA, in the Middle East and North Africa fuel subsidies are equivalent to more than 20% of government revenues.

Hundreds of millions of people across India do not have access to electricity

They can also lead to "unsustainable demand patterns", says Paul McConnell at energy consultants Wood Mackenzie. In some Middle Eastern countries, he says, "supply growth is not keeping up with demand". Hence why the gas-rich United Arab Emirates is looking to develop a nuclear industry.

Equally in Egypt, subsidised low petrol prices were sustainable while domestic oil production was high, but as the oil industry has declined, subsidies have become a huge burden. And Egypt is not alone - many countries in the Middle East, South East Asia, South America and Africa heavily subsidise petrol.

Artificially high demand based on these subsidised, cheap prices also accelerates greenhouse gas emissions linked to climate change.

'Inefficient and unfair'

Finally, and somewhat counter-intuitively, they tend to increase the gap between rich and poor. The poorest in developing economies do not own cars or power-hungry appliances, so benefit little from cheap petrol and electricity.

"In general, a very small proportion of subsidies reach the really poor," says Mr Varro. "They are an inefficient and unfair way to help the poor."

In fact, according to the IMF, the richest 20% get six times the benefit of the poorest 20%.

Subsidy cuts are very unpopular among people who are used to cheap fuel

As IMF chief Christine Lagarde said late last year: "Energy subsidies are enormous in scale, and they help the people who need them least. Taking action on this issue alone would be good for the budget, good for the economy, and good for the planet."

Indeed in 2009, the G20 committed to phase out "inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption", but progress has been painfully slow.

Governments face strong resistance whenever they try to cut fuel subsidies

Some reforms have been announced. For example India has said it will allow power companies to pass on the cost of more expensive imported coal, China has increased natural gas prices for non-residential users, while just last week Iran cut subsidies on petrol, following similar moves by Nigeria and Indonesia.

But fundamental and widespread reform appears a long way off. The reason is obvious - subsidy cuts are hugely unpopular among the wider population and are, therefore, a political minefield.

Coal subsidy cuts in Spain sparked protests by miners worried about their jobs

They may not help the poorest and most vulnerable, but cheap fuel benefits an awful lot of people, many of whom are happy to take to the streets in protest at the prospect of price rises on the back of subsidy cuts.

"It's deluded to think political sensitivities will go away, but that doesn't mean [getting rid of subsidies] will never happen," says Mr Varro.

Without a concerted and co-ordinated global push, however, they may be with us for a very long time.