'I wanted to hire people better than me'

- Published

Tanya Beckett reports on Hungary's journey to the free market

Setting up a business during Communist-era Hungary was easy, says Gabor Bojar, founder of software company Graphisoft.

"It's true that there was no access to capital, no access to the market, we didn't have passport to travel for example.

"But there was something which was much more important and that was access to talent.

"And attracting the best talent at that time was easy because it was the first opportunity [for many] to do something and prove that you can do better."

Graphisoft, now an international company, was one of the first private businesses to have been founded in Hungary under the Communist regime.

It was more liberal than others in the former Soviet bloc, and in 1982 new rules were introduced allowing small enterprises to exist.

Mr Bojar jumped at the chance.

"I wanted to hire people who were better than me," he says.

"It came from the frustration of my first job in a state-controlled company. I was shocked to learn that my boss was not happy if I was good.

"After a while I understood that if I am good I can endanger his position."

If a company is privately owned, he explains, normal human selfishness means that you want to hire the best people.

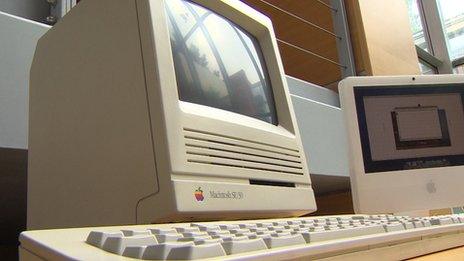

One of the first Macintosh computers is now on display in Mr Bojar's office. He smuggled this into Hungary to help develop his software company

Hungary is a country with a history of good ideas. Mr Bojar's office is just along the corridor from that of Erno Rubik, inventor of the Rubik's cube.

The inventor of the ballpoint pen, Laszlo Biro, was Hungarian, as was the man behind the first helicopter and the discovery of vitamin C.

Perhaps one of the most famous businessmen is the billionaire hedge fund manager and Hungarian emigre - George Soros.

George Soros set up institutes in many former Soviet bloc countries that are committed to promoting democracy

He left in 1947 - initially for London, ending up in the US.

Now in his 80s, he still comes back regularly.

So regularly in fact that a visit from him is no longer an item on the news, as it once was.

Just a couple of years after the birth of Graphisoft, Mr Soros was setting up the first of his many institutes in the former Soviet bloc devoted to promoting democracy - and ideas that undermined the Communist ideology.

'Morally clear'

He makes the point that the change was more a collapse of the old system than great conviction in a new one and that bringing one system down is harder than setting a new one up.

"It was a collapse but the situation was morally very clear, really quite black and white. Even the people in the regime realised that there was something wrong with the regime, so they were ripe to fall," he says.

"It was a regime that fell because of its own incompetence."

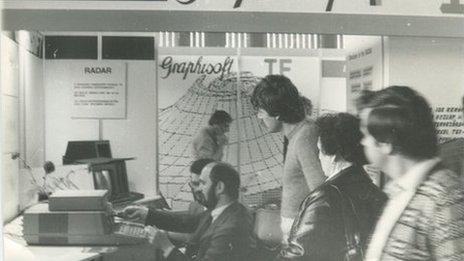

Mr Bojar says he sensed change was afoot in 1983 when he nervously applied for a visa to travel to Vienna for a day to give a presentation about his new company. Instead of being declined, he was told: "Comrade, thank you for bringing in some hard currency."

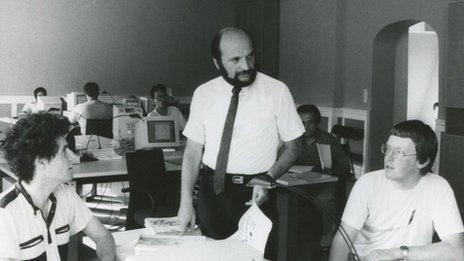

Mr Bojar took advantage of legislation in Hungary in 1982 allowing private enterprises

In the early days none of the Graphisoft employees had passports to travel

In many ways Hungary had a head start in the free market compared with the rest of the Soviet bloc. By 1989, when the Communist regime collapsed and the Berlin Wall fell, Graphisoft was already preparing to open up an office in San Francisco.

But despite Hungary's initial advantage, some say it hasn't realised its full potential. Growth has been faster in neighbouring Poland, for example.

"We used to think the transition would take 25 years, now it might be 45," says economist Laszlo Matyas, at the Central European University.

He's keen to point out that it's not all bad - the budget deficit is below 3% - a feat which many of its Western counterparts have not managed. Unemployment is about 8% - not great but below the EU average.

'Original sin'

But Mr Matyas describes one of the problems as that of "goulash oligarchs" - they're a little more benign than in other parts of the former Soviet bloc, indeed many of them are involved in philanthropic organisations, but they are a small group of businessmen, not more than 20, with a strong influence on the economy and politics.

"They behave like monopolies in some sectors and they really hamper competition," he says.

"It was the original sin of privatisation, those who were well-placed got a good start."

"It undermines the Hungarian economy heavily because it undercuts long-term investment in the economy. Foreign capital won't come and it undermines confidence."

Laszlo Matyas warns of the influence of what he calls "goulash oligarchs"

And that does seem to be borne out in the figures. According to Capital Economics, foreign investment fell from 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 to 17% of GDP in 2013, with 25% of GDP being a good benchmark for emerging markets.

Many lay that at the door of the unpredictable nature of the policy making of the recently re-elected right-wing government.

Mr Bojar has another theory. In his book he explains that he feels "that the entrepreneurial spirit that was so present in the early 1980s has been all but swallowed up by complacency".

While he is staunchly pro the EU, arguing that it provides better regulation, more stability and easier access to the European market for Hungary, he is concerned that being a member of it has also fostered a culture of learning to apply for grants - rather than spotting real opportunities on real markets.

"I am afraid that if we keep waiting for the EU or the state to save us, then that will lead to the same unmarketable sluggishness that we saw in the planned economy of the socialist state, when real competition was substituted by lobbying for money at different ministries," he says.