'Killer robots': Are they really inevitable?

- Published

Robots like these will be increasingly common

The robot tank is moving rapidly through the scrub on its caterpillar tracks. It comes to a sudden halt and its machine gun opens fire with devastating accuracy.

It may seem like science fiction but is actually a scene from a video featuring a robot being tested by the US Army, external.

It is just one example of how yesterday's sci-fi has become today's battlefield fact.

This miniature tank, only one metre long and made by Qinetiq North America, is one of a host of unmanned air, sea and land vehicles that are being used by militaries across the globe.

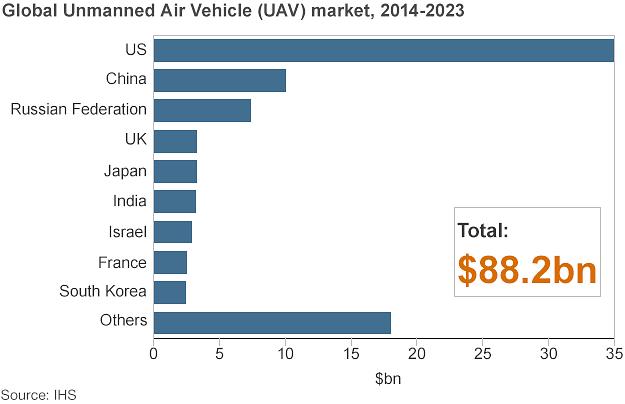

More than 90 countries now operate such systems, and it is an industry which will be worth $98bn (£58bn) between 2014-23, says research company IHS.

"The USA remains the prime market and a main driver," says IHS's Derrick Maple.

"But many countries are building up their indigenous unmanned system capabilities."

Qinetiq's roaming robots are designed to aid soldiers in reconnaissance or surveillance, or to go into heavily booby-trapped areas where it might be too risky to send in troops.

Kitted out with either a grenade launcher or a machine gun, the firm's latest version MAARS - Modular Advanced Armed Robotic System, external - is certainly lethal, but independent it is not.

It relies on a soldier controlling it remotely, and only operates up to distances of about 800m (2,600ft).

However, many critics worry that marrying advances like these in robotics and miniaturisation, with developments in artificial intelligence (AI) could lead, if not to the Terminator, then perhaps to its crude precursor.

Others argue that such AI developments would take many decades, and that for the foreseeable future there will need to be a "human in the loop", overseeing such systems.

'Fire and forget'

Yet already, a few autonomous weapons are in use which themselves decide whether or not to attack a target.

Take Israel's Harpy drone, external, for instance.

IAI's Harpy drone makes it own decisions whether to attack an enemy radar

This is what its manufacturers, IAI, call a "fire and forget" autonomous weapon - or a "loitering munition" in military jargon.

Once launched from a vehicle behind the battle zone, Harpy - effectively a guided missile with wings - loiters over an area until it finds a suitable target, in this case enemy radars.

Crucially, once a radar is detected it is the drone itself that decides whether or not to attack.

True, Harpy is only launched if its operators suspect there will be enemy radars to be attacked, but automation like this is likely to become more common.

Yet the real obstacle to the more widespread use of what some call "killer robots" is getting them to tell friend from foe.

"A tank doesn't look that much like a pick-up truck", says defence expert Paul Scharre, from the Centre for a New American Security., external

"But an enemy tank and a friendly tank might look pretty similar to a machine.

"Militaries are not going to want to deploy something on the battlefield that might accidentally go against their own forces."

It is a point echoed by General Larry James, the US Air Force's deputy chief of staff for intelligence.

"We are years and years away, if not decades, from having confidence in an artificial intelligence system that can do discrimination and make those decisions."

It is the United States which dominates the market for Unmanned Air Vehicles (UAVs) - over the next decade it is forecast to spend more than three times as much on UAVs as China - the next biggest spender.

UAVs also account for the bulk of spending on unmanned systems as a whole - budgets for land or sea-based systems are small by comparison.

Despite the difficulties in developing this technology, the US defence department's own 25-year plan, external published last year, says that "unmanned systems continue to hold much promise for the war-fighting tasks ahead".

It concludes by saying that once technical challenges are overcome, "advances in capability can be readily achieved... well beyond what is achievable today".

US drones have now dropped more bombs than Nato planes did in Kosovo in 1999

Drone's eye view of a target on a training mission

'You can't disinvent it'

One of those at the forefront of this research is Sanjiv Singh, robotics professor at Carnegie Mellon University and chief executive of Near Earth Autonomy.

Working for the US military and Darpa, the US defence research agency, his team has successfully demonstrated an unmanned autonomous helicopter.

Using remote-sensing lasers the aircraft builds terrain maps, works out safe approaches and selects its own landing sites - all without a pilot or operator.

They are now working on developing autonomous helicopters for the military, external which could carry cargo or evacuate casualties.

This will be a huge step away from traditional drones which, he says, "are driven by GPS-derived data".

"If you make a mistake in the flight plan, then they'll drive happily into a mountain if it's in the way."

With all the money being put into this sector, autonomous weapons systems will eventually be developed, says independent defence analyst Paul Beaver.

"It's just like nuclear weapons, you can't disinvent it," he told the BBC World Service's Business Daily programme.

Alarmingly, it is not rogue states that he is most worried about.

"I think we're about a decade away from organised crime having these sorts of systems and selling them to terrorist groups."

Opponents say 2,500 people have been killed by US drones in Pakistan alone since 2004

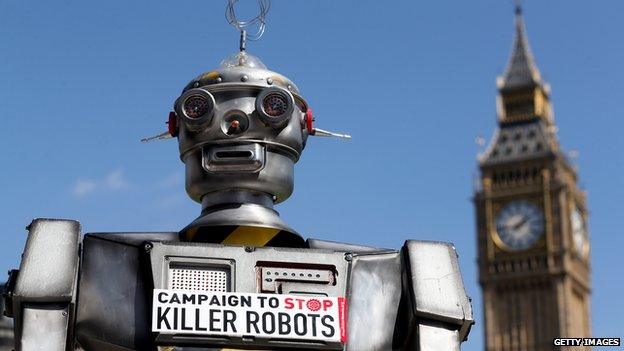

Campaigners want fully autonomous weapons, or "killer robots", banned now

'Take action now'

Earlier this month delegates from 117 countries met at the UN in Geneva to discuss a ban on such lethal autonomous weapons systems, external.

Even though the technology for "killer robots" does not yet properly exist, campaigners say the world needs to act now.

"There are so many people who see these as inevitable and even desirable, we have to take action now in order to stop it," says Stephen Goose of Human Rights Watch., external

"There's an urgency, even though we're talking about future weapons."

Yet in focusing on military uses of autonomous drones, we might be missing the bigger threat that increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence may pose, external.

"The difficulty is that we're developing something that can operate quite quickly and we can't always predict the outcome," says Sean O'Heigeartaigh, of Cambridge University's Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.

In 2010, for instance, computer trading algorithms contributed to the "flash crash" that briefly wiped $1 trillion off stock market valuations.

"It illustrates it's very hard to halt these decision-making processes, because these systems operate a lot quicker than human beings can," he says.

A robot like this is unlikely to be on a battlefield any time soon

Killer computers, not killer robots?

Paradoxically, it is the civilian and not the military use of AI that could be the most threatening, he warns.

"As it's not military there won't be the same kinds of focus on safety and ethics," says Dr O'Heigeartaigh.

"It is possible something may get out of our control, especially if you get an algorithm that is capable of self-improvement and re-writing its own code."

In other words, maybe it is not killer robots we have to worry about, but killer computers.

- Published9 May 2014

- Published2 February 2014

- Published18 December 2013

- Published31 October 2013