Battery tech playing catch-up with energy-hungry mobiles

- Published

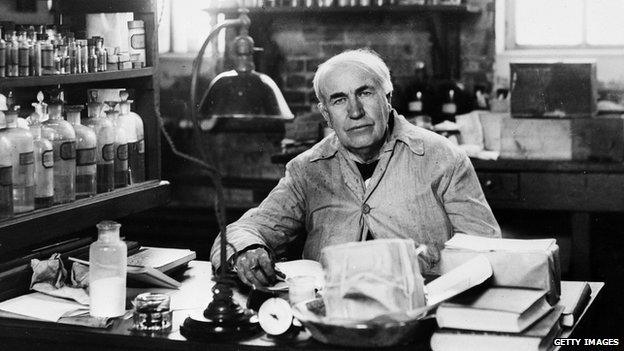

Battery technology needs a jump start: lead-acid car batteries have been around for 150 years

Mobile devices have transformed our lives, giving us the freedom to talk, work, watch and listen on the move.

But unplugged from the mains, they only last as long as the energy held within their batteries.

And there's the rub.

While scientists are constantly dreaming up new ways to generate and bottle energy - from rhubarb and paper to viruses and urine - commercial battery technology has changed remarkably little in the past 50 years, particularly when compared with the advances in the devices they power.

As Tim Probert, editor at Energy Storage Publishing, says: "The battery industry is pretty conservative. It says a lot that we are still using very old technology like lead-acid in batteries.

"Breakthrough technologies are great but they need a reality check - this industry is all about small, incremental improvements."

Slow moving

The humble AA battery has been around since the 1940s and is based on 19th Century technology. But it still has a 15% share of the global battery market, along with other alkaline batteries.

And the lead-acid battery, which is fundamental to most combustion engine-powered cars, was invented more than 150 years ago and holds a 20% share of the market.

Clearly the battery industry, which is worth almost $90bn (£54bn; 66bn euros) globally, is not keeping pace with innovation in consumer electronics.

AA batteries were standardised in the 1940 but are still widely used in many consumer devices

Even the near-ubiquitous rechargeable lithium-ion battery, which powers most modern gadgets, was invented in the 1970s.

It has about a 40% market share.

Electric vehicle pioneer Tesla, the brainchild of serial entrepreneur and billionaire Elon Musk, uses so-called 18650 lithium cells - "essentially old laptop batteries", according to Mr Probert - to power its cars.

Most laptop manufacturers gave up on 18650s long ago, but Tesla believes this old tech still has a future, and even has plans to build its own "gigafactory" to produce them.

"By choosing smaller, cylindrical cells, we have been able to save on manufacturing costs," explains Tesla's Laura Hardy.

"Smaller cells, which can have a better energy density, gave us more flexibility in packaging the cells and creating the battery pack."

By putting 7,000 of these cells together, Tesla's Model S Sedan is able to achieve a range of up to 300 miles, considerably more than many of its competitors using more advanced battery technologies.

Solid improvement

Most other manufacturers use pouch cells, which involve lithium cells being placed side by side like slices of bread. The danger here is the risk of "thermal runaway", where one cell short-circuits and produces so much heat it sparks a ripple effect and the battery blows up.

This is thought to be what happened to Boeing's Dreamliner passenger jet in Japan at the beginning of last year.

The next generation of lithium-ion batteries will help solve this problem by replacing flammable liquid electrolyte with safer, solid-state components. This type of battery is also more powerful per unit.

Most electric cars rely on lithium-ion batteries, a technology developed in the 1970s

Some companies are also trying to develop lithium-sulphur batteries, which promise to have five times the energy of a standard lithium-ion.

Mr Probert says UK-based Oxis Energy is making some real progress in this area, but warns that we should not expect a "quantum leap" any time soon.

New discovery

The more realistic and exciting developments are taking place away from pure battery technology.

The first is wireless power - charging your gadgets without having to plug them in to the mains.

This is a market that could be worth $5bn by 2016, according to IMS Research (now part of IHS).

One company pioneering this new technology is Ossia, with its Cota remote power system. Founder and chief executive Hatem Zeine stumbled across the idea while researching wireless signal management.

.jpg)

Cota inventor Hatem Zeine believes the best inventions are discovered by accident

He discovered that a small amount of power is transmitted alongside the radio waves, and set about researching how best to focus the signal from many antennae working in unison as a means to charge devices remotely. In 2013, more than decade later, Mr Zeine launched Cota.

"Cota comes in two parts - a charger and a power receiver," Mr Zeine explains. "Think of the charger as similar to a wireless router, and the receiver as a button battery."

"The receiver sends out a low power signal to the charger, which in turn sends back a signal from each of its thousands of antennae, targeted specifically at the receiver itself. The receiver will then track the device constantly."

The benefits are obvious. You no longer have to worry about recharging your phone or laptop, as it will do so automatically whenever it is within range of a charger.

This means the battery doesn't need to store as much energy, and so can be made much smaller - the holy grail for all consumer electronics manufacturers.

Battery tech has moved slowly: Light-bulb inventor Thomas Edison developed a nickel-ion battery in 1901

Mr Zeine believes the applications for wireless charging go way beyond consumer electronics and into medical devices, production lines and construction.

Indeed, he envisages a time when we need far fewer power sockets because remote chargers will be installed throughout our homes, offices, public buildings, cars and trains.

Water in, water out

Swedish company MyFC, an offshoot of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, has developed Powertrekk, a portable fuel cell that can generate energy to power all manner of consumer devices.

"Our fuel cell is an electro-chemical device that converts hydrogen into protons and electrons. The protons go through a membrane and react with oxygen, so the only bi-product is water," explains Bjorn Westerholm, MyFC's chief executive.

Powertrekk, which provides up to 5 watts of power, incorporates a lithium-ion battery to provide the initial charge, before the fuel cell takes over. Once the device is fully charged, the fuel cell then recharges the battery.

Powertrekk's fuel cell turns the reaction between hydrogen and oxygen into electricity

This means you can power a device with just water and a small sodium silicide refill canister, anywhere at any time.

Powertrekk is being sold in 24 countries including, as of late May, the UK. Since launching a year ago, MyFC has sold 10,000 units.

Given that mobile phones and tablets are currently selling at a rate of about two billion a year, "we haven't even scratched the surface yet", says Mr Westerholm.

And while battery technology continues to develop at such a slow pace, there will be plenty more opportunities for eager entrepreneurs to elevate the art of energy generation and storage.