10 ways to cool the housing market

- Published

- comments

Back in 2012, a key question for Britain's brainiest economists was how to get the housing market moving again.

But just 18 months on, the return to booming prices has been so sudden that the Bank of England is now hinting it may step in to do exactly the opposite: to slow things down.

According to one of the Bank's own top brains, no-one had predicted the "microwave" effect.

Spencer Dale, the Bank's chief economist, said that just like cooking food, the housing market can pass from cool to hot in the matter of a "few economic seconds".

Had he continued the analogy, he might well have warned about isolated hotspots being particularly dangerous.

So what steps could be taken to cool the market down - or at least to lose the excess steam which all of a sudden has made it such a safety hazard?

The interactive content on this page requires JavaScript

1. Turn down the temperature

Perhaps the easiest fix is to make it harder for homebuyers to borrow money. The Bank's governor, Mark Carney, has already expressed particular concerns about those taking out high loan-to-value mortgages.

Some lenders currently offer loans that are more than five times a borrower's income. The Financial Policy Committee (FPC) could act to limit such borrowing as soon as next month.

Borrowers could also face stricter "stress tests" - meaning that lenders would have to ensure they could still afford repayments if interest rates rose significantly. To an extent this is already happening under the Mortgage Market Review (MMR), which requires lenders to ask tougher questions about affordability. But the FPC could make the rules tougher, or more explicit.

2. Freeze out the lenders

Aside from making it harder to borrow, the FPC could also make it more difficult to lend. Banks and building societies might be forced to raise more capital - i.e. put money aside - to cover riskier borrowers defaulting on their repayments. Doing that would make mortgages more expensive for new borrowers, and so would dampen demand.

The banks could face tougher stress tests of their own too, having to prove they would survive in a world of rising interest rates and falling house prices.

One interesting idea raised by MPs on the Treasury Committee is whether lending criteria could be specifically tightened in property hotspots, such as London, Cambridge or Aberdeen.

This would be a much more flexible tool - allowing demand to grow in areas like Northern Ireland and the North East of England, where prices have been slow to increase. However, although Spencer Dale said this idea is theoretically possible, the FPC is not thought to be considering it seriously.

3. Raise interest rates

While Mr Carney has promised not to use base rates as a means to cool the market, the expectation that they could rise early next year may already be having the necessary effect. Over the last few weeks some mortgage rates have crept up from record lows.

But the base rate tool is a very blunt instrument. A rise could choke off economic growth. And like all the above methods, it would have no effect on cash buyers, who can account for a third of the market, and who are driving price rises in London in particular.

4. Limit Help to Buy

Many economists have argued that the government's Help to Buy scheme - which allows buyers to find a deposit of just 5% - is helping to inflate house prices.

The Bank could advise the government to scale back on the scheme. The Business Secretary, Vince Cable, has already said it should apply to properties up to a maximum value of £350,000, rather than the current £600,000. Nick Clegg, the Deputy Prime Minister, said the government should follow the Bank's advice.

But if Help to Buy has helped to put up house prices, remember it has also helped to increase the supply of housing. Private housebuilding has increased by 34% in the year since the scheme started. Without it, the shortage of houses might have been worse, so prices might have been even higher.

5. Build more houses

And that brings us to the other side of this equation: supply, as well as demand. Mr Carney has already identified that while he can do something about demand for housing, he cannot build a single house himself. His own country, Canada, builds more houses than the UK, even though it has nearly half the population.

In the year to March there were 112,630 houses completed in England, external, a rise of just 4% on the previous year. Experts believe the UK as a whole needs to build at least 250,000 homes a year to meet demand, and put a brake on prices.

6. Build on the greenbelt

Although building on brownfield sites - like old hospitals or factories - is preferable, there are simply not enough sites to go around, particularly in London and the South East, where the population is rising fastest.

Sam Bowman, research director at the Adam Smith Institute, has argued for a while that local authorities should allow building on greenbelt land. "By rolling back the greenbelt by just one mile around London, we would have space for one million new homes," he said this week.

But even the Home Builders Federation, which wants more land made available, does not agree with that idea.

7. Ban foreign ownership

From Russian oligarchs to George Clooney, foreigners moving to central London have helped to raise property prices by as much as 18% this year. In theory that trickles down to the lower reaches of the market, affecting house prices for all. So could foreign sales be limited?

The company selling new flats at Battersea Power Station in London said they would only market them to those "based in the UK, or who have a commitment to the UK". However, agents in Hong Kong are still free to try to sell them to clients in Asia. In practice such restrictions are very difficult to achieve.

Foreigners buying a home worth more than £500,000 through a company are already subject to 15% stamp duty.

8. Build pre-fabricated houses

Last year Housing Minister Mark Prisk set up a working group to look at the possibilities of building more pre-fabricated houses. This could enable thousands of flats and homes to be built at a fraction of the cost of traditional properties, and so in theory ease the pressure on prices.

But do not imagine 1960s Butlins-style holiday camps. These involve modern, factory-built units that come complete with built-in kitchens and plumbing.

Ten years ago the Labour peer, Lord Prescott, had the same idea, hoping to build homes that cost just £60,000. The resulting development, known as "Lego Land", can still be seen in Milton Keynes.

9. Incentivise small builders

Large builders need large sites to make the returns demanded by shareholders. But in many countries, most properties are built on small sites, by small-scale builders.

According to Jan Crosby of accountants KPMG, 80% of homes in Austria are built in this way. He suggests that such builders could be incentivised to build more, with the help of cheap loans. More people could also be encouraged to build their own homes, where significant savings are possible.

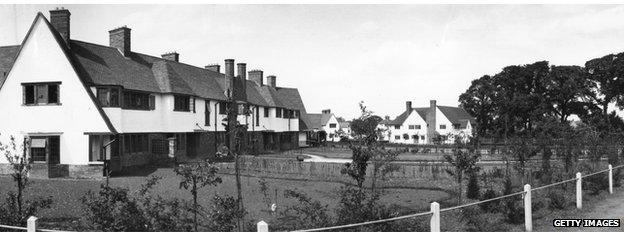

10. Build more garden cities

The government has announced up to three garden cities will be built, the first of which is planned for Ebbsfleet in Kent. But while that may ease the housing shortage in that area, the provision of 15,000 new homes over a long period of time is unlikely to have a significant impact on property prices across the UK.