Investing in property... with £1,000

- Published

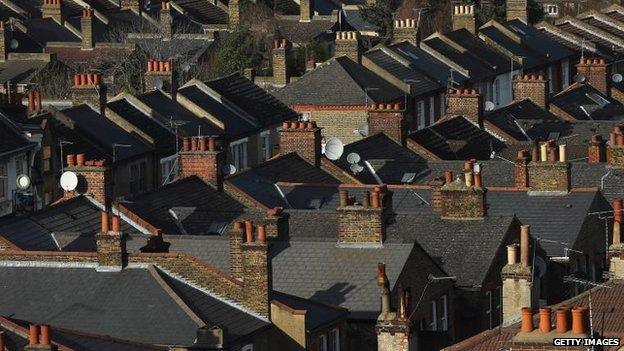

Investors have been interested in UK property for many years

Ever fancied investing in a buy-to-let property, but cannot afford to do it on your own? A new scheme allows investors to club together to buy a cheap house, do it up, then rent it out. But is it a good idea?

One thousand pounds is all Hugh Hutchinson, a young lawyer in London, is putting towards the buy-to-let property he is hoping to be part of.

"While I make a decent salary, I don't have tens of thousands of pounds sitting in the bank and nor do I have the ability to ask my parents for that sort of money," he says.

Mr Hutchinson is bidding to be part of a group of investors who will fund the purchase of a city centre flat in Manchester, an opportunity advertised by Property Moose.

The company launched earlier this year and is one of a number of companies springing up offering this kind of investment. They organise everything and take their own slice of the investment for doing so. Each house is bought through a special purpose vehicle and shares are allocated to investors.

Hugh Hutchinson says he is hoping for a better return than he would get with a savings account

"I just wanted to find a scheme that allowed you to invest a relatively small amount of money to see the upside in property in a way that didn't require the usual hurdles that I found quite obstructive," Mr Hutchinson says.

"I'd be happy with anything more than I'd be making if it was just sitting in my bank account, to be honest. I would like to see a 5% plus per annum."

Investments

Five per cent looks like an excellent return at the moment, but is it really that straightforward?

The company Mr Hutchinson is investing with does not offer any guaranteed returns, but other companies do offer what look like very tempting rates.

Investors with rival company The House Crowd, which has been operating in the North West of England since 2012, have two options to choose from.

Firstly, there is the income-only model, which pays investors a fixed 7.5% a year from the rental income based on the share they put in. So, an investor putting £3,000 into a property would receive £225 every year (the average investment made per property is £3,700).

Secondly, there is the profit-share model, which pays investors a fixed 6% a year i.e. £180 if they'd invested £3,000. And then they would also get their share of half the profits, the company says, when the house is sold. The company takes the other half.

Falling prices

This rather assumes the house you invest in will go up in price, but what if it does not?

Frazer Fearnhead says this is a long-term investment

The company will continue to rent the house out, says Frazer Fearnhead, the managing director of The House Crowd. The truth is when they have tried to do quick do-up and sell-on jobs in the past, they did not turn out to be the get-rich-quick schemes investors had hoped.

"It didn't work, to be frank," he says. "We've sold one property for a decent profit. Another one is just about to sell now, but we've had five offers fall through on that property.

"That will make about a 24% gain when we sell it, so not bad, but it's taken a long time to do that. And then three others that we intended to do that for, we couldn't do and are now being rented out."

But even if you were to consider it simply as an income-only investment, 7.5% on that sounds rather ambitious. The national average rental yield is about 5%, according to the Association of Residential Letting Agents (Arla).

Rental yields have been falling as house prices have been rising faster than rents, Frazer Fernhead concedes, but he thinks his company has got a strategy which will continue to give investors good returns.

"Most of our tenants are on housing benefit. Those rental levels are absolutely fixed over a broad geographical area, but within that broad geographical area you've got little pockets where the housing stock is cheaper than in other areas, so you get the same rent but the houses are cheaper to buy. We've identified those areas, and that's how we can maximise the yields," he says.

But this strategy could be risky, according to David Cox, the managing director of Arla.

While housing benefit is paid direct to the landlord at the moment, he points out, there are plans for it to be paid directly to the tenant, under the government's new Universal Credit welfare programme, which is being rolled out across the country by autumn 2017.

He also says investors need to be sure that the people managing the projects know how to rent out properties, so that void periods when the property lies empty are kept to a minimum.

Pitfalls

There are other potential pitfalls investors should be mindful of, according to Justin Modray, from the Candid Money website.

He points out the charges associated with this sort of scheme, which are not insignificant. Property Moose, for example, charges 5% of the amount that is invested upfront. It then takes a 15% fee from the annual dividend and final sale.

And how do you get your money out? This certainly is not "easy access", like an Isa, Mr Modray says.

"If you want to get your money back, you could end up waiting possibly even a year or more in a bad situation, and if it relies on them selling the property, that could take many months before the money actually materialises," he says.

"If the property market falls - and there's every chance it could do given prices look quite toppy at the moment - then you could actually end up losing money."

Getting your money out is simply a question of finding another investor willing to buy your share, Frazer Fernhead says, and that is something that has always worked out fine so far.

That might be relatively easy to do in a rising market, but would surely be much more difficult in a flat or falling market.

This material is for general information only and does not constitute investment, tax, legal or other form of advice. You should not rely on this information to make (or refrain from making) any decisions. Links to external sites are for information only and do not constitute endorsement. Always obtain independent professional advice for your own particular situation.

Listen to the full Money Box report on on BBC iPlayer.