Drought hits Brazil's coffee industry

- Published

Farmer Diogo de Oliveira Marcio says many of his coffee cherries are shrivelled and dry

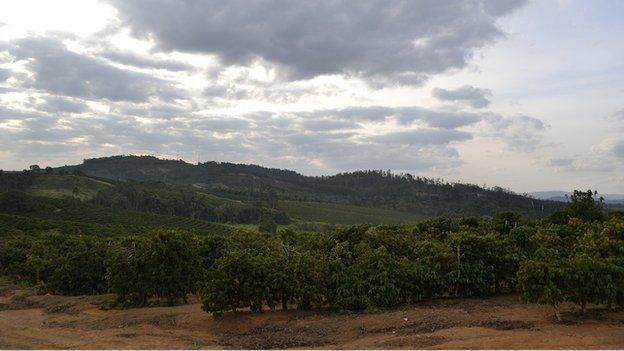

Brazil's coffee fields are busy at this time of year - from now until September, thousands of coffee pickers will spend their days in the fields stripping the bushes and bagging up the beans.

But the bushes are not as fruitful as they have been in recent years. January and February, which normally host the rainy season, were the driest in decades and that has hit the country's coffee growing region hard.

Katy Watson shows the effect the drought in Brazil has had on coffee plants.

Coffee farmer Diogo de Oliveira Marcio shows me the impact on his crop - an entire field of coffee bushes with drooping leaves, desperate for water.

He points out that the younger bushes have faced the biggest problems. Their root systems are not as established so they have not been able to get the water that they need.

"The fruit has been lost and there's no way back," he tells me, cracking open some cherries which contain the beans. "They are all shrivelled and dry - there's nothing inside."

One expert told me that on average, 100kg of coffee cherries picked from a tree normally yields about 50kg of green (unroasted) coffee beans.

The lack of water, though, means that from younger trees farmers are only getting about 30kg of green coffee this year. It is slightly higher for older trees - between 35 and 40kg.

Brazil is the world's biggest coffee producer, accounting for about a third of global production. It produces more than half of the world's arabica coffee - the most popular bean used in espressos and cappuccinos globally.

So the drought has had an impact on prices. And it has coincided with a leaf rust that has damaged crops in Central America, further hiking up prices.

Coffee farms in Brazil have felt the harsh effects of the drought...

...which will eventually lead to higher prices for coffee on shop shelves

In November, arabica futures for July delivery stood at $1.09 a lb on the ICE Futures US exchange. The price all but doubled to more than $2 in April and is now hovering around the $1.70 mark.

Although coffee farmers are getting more for their bags, it cannot compensate for a poor harvest.

"Coffee has risen in price but it still costs us a lot," says Diogo. "We're spending lots of money on people to harvest the beans which are of a lower quality so it's really difficult."

Katy Watson explains the rise in the price of coffee.

A short drive away from Diogo's coffee farm is Espirito Santo do Pinhal - the centre of the area's coffee economy.

Farmers at the local co-operative, COOPINHAL, are bringing their harvested beans to store in the warehouse.

The beans are sorted according to size and quality in the warehouse

They are then bagged up and either stockpiled or sold

Talking to farmers here, the concern is not just about this year's crop, but next year's too.

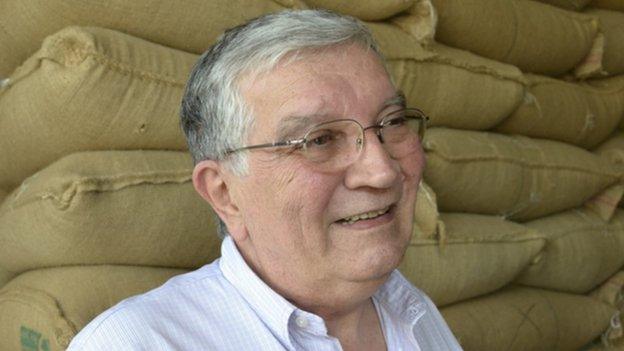

"Farmers are worried about the effect the drought's had," says Alexandre Husemann da Silva, the president of the co-operative.

"The lack of water meant that the plants grew less than normal - so they only produced beans in the part that grew. Because of that, losses will be higher next year than this year."

But despite prices rising on concern over the crop size, this year so far has not seen a supply problem in the global coffee market.

Alexandre Husemann da Silva says farmers are worried about next year's crop

Producers have been selling their stocks from previous years which has kept supply up in the market. And on the demand side, many big coffee buyers have locked in lower prices.

"Roasters buy in the futures market sometimes years in advance," says Mauricio Galindo of the International Coffee Organization. "This provides protection in case coffee prices start soaring."

Joao Staut, a director at exporter Qualicafex in Espirito Santo do Pinhal, says it is too early to speculate on whether next year's crop will be worse than this year's, but one thing is certain - the price of coffee for the consumer will eventually go up.

"Several roasters bought their needs some time ago but now they are covering the future and the future is not the same," he says. "It's unavoidable that you are going to pay more for your coffee in the coming months."

Back at the co-operative though, as the machines loudly sort the good beans from the bad, the focus is on selling the beans that have survived the drought.

In this noisy warehouse, the price of a cappuccino is not on producers' minds.

Pictures courtesy of Bob Phillipson.

- Published19 May 2014

- Published25 January 2014

- Published23 May 2013

- Published5 April 2014