What happens to your debts when you die?

- Published

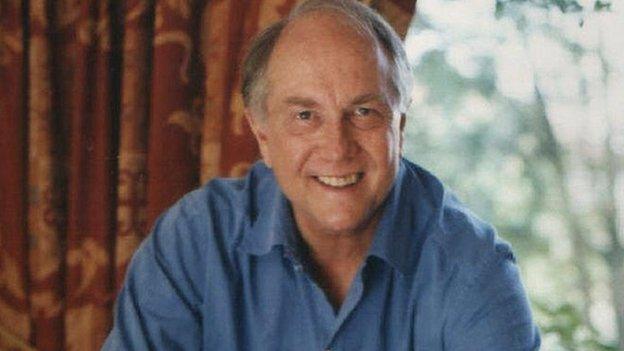

David Barber owes £35,000 and repays about £56 a month on a debt management plan

One in 50 people in their seventies has problem debt according to Age UK, but what happens if you cannot pay off these debts later on in life?

When David Barber travelled to Uganda at the age of 68 with a colleague to set up an ethical business venture, he hoped to help in the fight against poverty in the country.

"We ran up against quite a lot of opposition," he says. "The net result was that because neither of us were quitters, we actually finished up losing all our own personal money, as well as money which we'd borrowed."

"I went from being fairly comfortable, to coming back to the UK and having absolutely nothing left."

Now aged 75, Mr Barber owes £35,000 from bank loans and credit card debt. He is on a debt management plan (DMP), which is an arrangement between a debtor and their creditors to pay the debt. Regular payments are made to a licensed debt management company and the money shared between creditors.

Mr Barber pays about £56 a month on the plan - at this rate it would take approximately 52 years to pay back the full amount.

He is hopeful that a new network marketing business he has set up will thrive and he will be able to pay off the debt quickly and return to Uganda to continue the work he would like to do there.

However, if it does not succeed, he knows there is a strong possibility he could die in debt. "I think it's extremely likely," he says.

"And I'm not the only one who, when they die, the debts will still be there.

"I don't think any dead person particularly cares that they've got debts, but of course what that does mean is that what they can leave to their children is obviously far less, or probably non-existent in most cases, and that's the real problem with it."

With grown-up children in their forties Mr Barber says he has become resigned to this.

"It's a matter of regret, but the fact is my conscience is clear because I have tried, and am trying to do everything that I can and either it's going to work or it isn't."

A survey for the BBC found 69% of British adults in debt have not asked for advice on managing their debts

'Historic' debt

According to Caroline Hamilton, debt advice development manager at the Money Advice Service, when a person dies their debts do not automatically die with them.

"Technically speaking, if you pass away, it is the responsibility of your estate to pay any debts. If you have no estate, or the estate isn't sufficient to cover all liabilities, they get written off and creditors cannot chase surviving family members, no matter how big the debt. However, there are some exceptions."

With unsecured debts, if the debt is in joint names, it is likely that a next of kin may have signed a "joint and several liability agreement" when the debt was taken out, says Ms Hamilton.

This means if one of the party stops paying the debt, because of financial difficulties or death, the other named party would have to pay the balance.

Debt in the UK

277

people made bankrupt daily

31.5m

plastic card purchases each day in March

-

£6,065 avg household debt, excluding mortgages

-

£3,192 avg borrowing per adult

-

£28,756 avg owed per adult

With joint mortgages it depends whether the agreement signed was as beneficial joint tenants or as tenants in common, she says.

"Broadly speaking, if you are beneficial joint tenants, you both own the whole home, so if one of you passes away, the surviving party automatically becomes sole owner.

"If you are tenants in common, the deceased's share may form part of their estate.

"However, if one party has experienced a debt problem in the past and the property has been brought into the equation, for instance in bankruptcy, this can automatically change a beneficial joint tenancy into a tenants in common agreement and this isn't automatically reversed.

"This can mean that a historic debt problem can bring about surprises upon the death of one party."

Hiding problems

Ms Hamilton says if someone is struggling to keep up with debt payments, they should contact a free debt advice provider or speak to lenders directly.

"Some lenders may offer a moratorium, suspending payments entirely and making a claim on any estate once you pass away, or they may offer a complete write-off. It's at their discretion though," she says.

According to statistics from 2013 by the debt charity StepChange, people aged over 60 are disproportionately less likely to seek debt advice , externalthan young people.

However, it appears that at any age people are hesitant to seek help.

A recent survey conducted by Comres for the BBC found 69% of British adults in debt have not asked for advice on managing their debts. The poll surveyed 1,000 respondents between 23 and 25 May 2014.

Mr Barber, who also worked as a debt adviser at one stage in his life, says that those with problem debt often do conceal it.

"Most people try and hide the fact from everybody, they're not honest about it and part of that is they really don't look around enough to find out what they can do about it.

"It's almost as if they roll over and let the debt take over and control their lives," he says.

'I've just got to work'

According to Lucy Malenczuk, policy adviser at Age UK, many older people are also not aware of the support they can receive too.

"We know lots of older people are not claiming benefits, external that they're entitled to, and so it would be great to stop people having to take on debt that they perhaps don't need if they just got all the help they could."

Mr Barber's daily life is affected by his debt. He has had to sell his car because he cannot afford to run it and does not socialise because he cannot afford to go out, but he remains positive about the future:

"I've just got to work and try and do something to get myself out of it if I want to go back to the lifestyle I had before, and that is my motivation."

Find out more about the impact of debt in the UK on BBC Radio 5 Live, BBC Breakfast TV and BBC North West Tonight on Tuesday, 10 June.